For policymakers & media

This section provides an overview of the main legal arguments and judicial precedents contained in this Resource Center to counter extraditions to China, as well as the political arguments for the suspension of bilateral extradition treaties with the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong.

For a summary one-page factsheet, please click on the link Reasons for suspending extradition treaties with China and Hong Kong in the upper right corner of this page for a downloadable PDF.

EXTRADITIONS TO CHINA AND HONG KONG

China has a long record of gross human rights violations. Since Xi Jinping assumed power at the top of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012, we have witnessed a general and consistent further decline in the protection of fundamental human rights, both on the Chinese mainland and – increasingly – in Hong Kong.

Numerous democratic Governments and Parliaments, regional and multilateral bodies, UN Human Rights Mechanisms, Courts and non-governmental organizations have denounced the grave and ongoing violations of civil and political rights as defined by the UN Convention, the ongoing genocide and crimes against humanity in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, persecution on political, ethnic or religious grounds, the widespread and systematic use of enforced disappearances and torture to extract forced confessions, the absence of an independent judiciary, the lack of access to lawyers of one’s own choosing, and a consistent criminal conviction rate just shy of 100 percent.

For more on China's human rights situation, see section 3, UN reports, Country reports, Other reports.

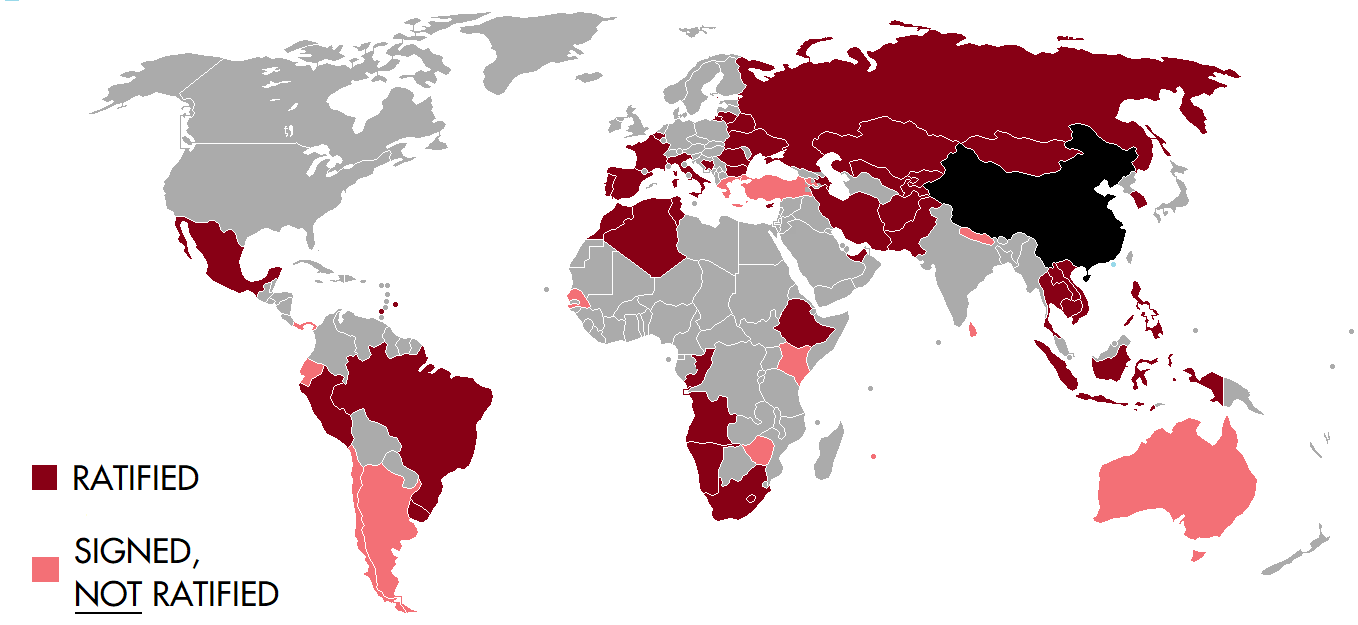

China has also invested heavily in extending its long-arm policing capacities abroad, both through judicial and extra-judicial means (for the latter, see Section 6). This has translated in the signing and/or ratification of a long series of bilateral extradition treaties (as well as mutual legal assistance treaties, prisoner swap treaties and various law enforcement cooperation agreements at both the bi- and multilateral level). Oftentimes, such treaties have been attached to a package deal of economic and cultural cooperation agreements.

*For details on the status of signed and ratified treaties see our reports, Hide and Seek and Returned Without Rights (downloadable as PDFs on the top right of this page).

The aim of such agreements is two-fold and mutually reinforcing: 1) Enhance bilateral police and judicial cooperation to extend long-arm policing capacities and create a global climate of fear for those fleeing persecution inside China; 2) Legitimize China’s judicial system: Chinese authorities have expressly and repeatedly claimed the signing of such agreements “effectively demonstrates China’s good image and the confidence of the international community in China’s rule of law”.

RISKS

Legitimization

China claims that bilateral extradition treaties “effectively demonstrate China’s good image and the confidence of the international community in China’s rule of law”.

In 2015, an Italian Court of Appeal ruled in favour of extradition to China and dismissed the defense’s claims of risk of torture and other inhuman and degrading treatment by stating that the “advanced stage of legislative approval of the bilateral extradition treaty signed between Italy and the People’s Republic of China on October 7, 2010, demonstrates the political will of the State parties to extradite wanted individuals […] on the basis of mutual reliance on the effective recognition of fair trial standards and the full respect of fundamental human rights in the respective detention facilities”.

A similar assessment was made by Morocco’s Rabat Court of Appeal when it ruled in favour of the extradition of Uyghur human rights defender Yidiresi Aishan (aka Idris Hasan). It was the first extradition to China case following the ratification of the bilateral extradition treaty in January 2021, a treaty that had been part of a “package deal” of 16 economic and cultural agreements. While interim measures barring execution of the extradition were imposed by the UN Committee Against Torture following the Court’s ruling, two years later Idris Hasan is still in solitary detention in Morocco.

Moreover, standing extradition treaties with democratic nations directly contribute to China's ability to entice more countries into entering the “growing weave of international judicial and police cooperation”. During a 2020 court hearing in Cyprus, a representative for the Ministry of Justice testified how little attention had been paid to examining the human rights situation on the ground before the signing of the extradition treaty, as the fact that other European Member States maintained them was found to be sufficient grounds.

While the recent pilot judgment by the European Court of Human Rights may have significantly increased judicial protection within Council of Europe Member States, the maintenance of bilateral extradition treaties continues to send a political message that legitimizes China’s judicial system around the world.

Since May 2021, at least seven European Parliament resolutions calling for the immediate suspension of all bilateral extradition treaties with China and Hong Kong have been adopted by overwhelming majorities.

For an overview of European Parliament resolutions, see the downloadable PDF on the top right of this page.

Non-Refoulement

China’s abysmal record led the European Court of Human Rights to define China’s judicial and penitentiary system as a “general situation of violence” in its landmark Liu v. Poland judgment of October 2022 (Entry into Effect: January 31, 2023). This erga omnes assessment effectively bars all extraditions to China from the territory of the 48 Council of Europe Member States as they would constitute a violation of the principle of non-refoulement under the Convention (article 3).

Non-refoulement is an absolute and core principle of international refugee and human rights law that prohibits States from returning individuals to a country where there is a real risk of being subjected to persecution, torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or any other human rights violation.

Similar assessments have been consistently made by relevant UN Human Rights Procedures with regard to individuals at risk of extradition to China: “No State has the right to expel, return or otherwise remove any individual from its territory whenever there are 'substantial grounds' for believing that the person would be in danger of being subjected to torture in the State of destination, including, where applicable, the existence in the State concerned of a consistent pattern of gross, flagrant or mass violations of human rights.”

Both the European Court of Human Rights and UN experts have also repeatedly stressed that the existence of a bilateral agreement on extradition, or diplomatic assurances, where provided, do not release States from their obligations under international human rights and refugee law, in particular the principle of non-refoulement.

In the past, some Governments have erroneously argued that the maintenance of bilateral extradition treaties increases the level of protection for individuals targeted by China with extradition requests. This is factually untrue. International, regional and national legal instruments provide all the - if not more - judicial safeguards and human rights protections contained in any given bilateral extradition treaty. The proof can be found in the relevant case law itself, where for example a Czech court denied an extradition to China on human rights grounds and international human rights conventions, despite the absence of a bilateral extradition treaty.

See an overview of judicial decisions in the application of the principle in Previous Court Rulings.

Arbitrary Detention and related risks

The European Court of Human Rights’ Liu v. Poland pilot judgment further condemned Poland for the lengthy deprivation of liberty during judicial proceedings on the request of extradition, ruling it to have constituted arbitrary detention (violation article 5 §1 of the Convention).

Numerous reports have consistently denounced the Chinese authorities’ abuse of international judicial and police cooperation mechanisms (such as INTERPOL) to persecute human rights defenders, political opponents and individuals belonging to ethnic or religious minorities, exposing them to the risk of lengthy stints of arbitrary detention in other countries’ jurisdictions.

Furthermore, while extradition or deportation through official bilateral judicial channels may be avoided, the execution of international arrest warrants may aid the Chinese authorities in locating a target and inadvertently assist them in the execution of extrajudicial measures to force their return to China. Democratic authorities must pay increasing attention to this issue.

Hostage Diplomacy

The maintenance of bilateral extradition and mutual legal assistance treaties or – worse – prisoner exchange agreements may expose nationals of other countries to the risk of arbitrary detention and sham trials in China as a means of hostage diplomacy to exact the return of wanted individuals.

In February 2021, Canada launched the Initiative against Arbitrary Detention in State-to-State Relations, stating: "Around the world, foreign nationals are being detained arbitrarily and used as bargaining chips in international relations. Such tactics expose citizens of all countries who travel, work and live abroad to greater risk. Not only is this practice contrary to international law, but it also undermines friendly relations between states, global cooperation, travel and trade." While the Initiative and accompanying Declaration signed by 74 countries (and endorsed by the European Union) do not single out China, it came at the height of tensions over the almost three-year long unlawful and arbitrary detention of Canadian citizens Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor on trumped up espionage charges, in a Chinese bid to stop or otherwise influence extradition proceedings between Canada and the United States of Meng Wanzhou, chief financial officer of Chinese telecoms equipment giant Huawei.

Chilling Effect

The recent increase in the number of extradition treaties, in combination with China's more assertive global stance and growing extraterritorial provisions in its criminal and national security legal framework are putting a severe strain on the enjoyment of fundamental rights such as freedom of expression and movement for citizens around the world.

In recent years, citizens of multiple democratic nations have been expressly warned against traveling to countries with standing extradition treaties with China or Hong Kong. These include activists, dissidents and sitting Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom and Denmark. Within the European Union alone, ten Member States* – including the seat of many European institutions, Belgium – maintain active extradition treaties with China, while two – Czech Republic and Portugal – maintain active extradition treaties with Hong Kong.

They directly contribute to the chilling effect Chinese authorities seek to instate around the world, effectively limiting individuals' ability to freely express themselves and associate.

*EU Member States with active extradition treaties with China: Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, France, [Greece (not ratified)], Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Romania, Spain.

THE CASE OF HONG KONG

Following the imposition of the so-called National Security Law (NSL) by Beijing, no real distinction can be made between the situation in mainland China or Hong Kong for the purposes of respecting the principle of non-refoulement. As the UN Human Rights Committee's findings on the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in Hong Kong of 27 July 2022 stated: “The Committee underscored the shortcomings of the NSL, including the lack of clarity of “national security” and the possibility of transferring cases from Hong Kong to mainland China, which is not a State party to the Covenant, for investigation, prosecution, trial and execution of penalties.”

The concern regarding the possibility of transferring a case from Hong Kong to mainland China is further exacerbated by articles 55 to 61 of the NSL, attributing discretionary power of jurisdiction to the Office for Safeguarding National Security of the Central People’s Government in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region constituted under that same NSL, and expressly instating mainland bodies (Supreme People’s Procuratorate and Supreme People’s Court) to exercise jurisdiction over the cases.

The express possibility of transferring “suspects” to the mainland for prosecution, as well as the possibility of unsupervised prosecution by mainland bodies and methods in Hong Kong, should clearly extend the cited application of the principle of non-refoulement to Hong Kong.

In fact, since Beijing’s imposition of the NSL in violation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration and Hong Kong SAR’s own Basic Law, ten democratic nations suspended their extradition treaties with Hong Kong as part of a package of responses to the new security law China has imposed on the region.

The European Council conclusions of 24 July 2020 provide that “as an initial response, the EU has decided to endorse a coordinated package responding to the imposition of the national security law, to be carried out at EU and/or Member State level, as deemed appropriate, within their respective areas of competence, ia. reviewing the implications of the national security legislation on the operation of Member States’ extradition and other relevant agreements with Hong Kong.” Since then, at least seven European Parliament resolutions have expressly called for the suspension of remaining bilateral extradition treaties with Hong Kong (and China) within the European Union. Today, only the Czech Republic and Portugal still maintain an active extradition treaty with Hong Kong SAR.

For more on post-Hong Kong NSL actions by democratic nations, please click the link to a downloadable PDF on the top right of this page.

CONCLUSION

The maintenance of bilateral extradition treaties rewards the Chinese authorities’ consistent pattern of gross, flagrant and mass violations of human rights, and expands its long-arm policing footprint around the world.

It makes signatories complicit in China's efforts to restrict individuals’ fundamental freedoms (chilling effect), engage in arbitrary detention and breach the non-derogable principle of non-refoulement. It may further expose its own nationals to the risk of hostage diplomacy in a tit-for-tat for the return of individuals wanted by Beijing or Hong Kong.

There is no argument of reciprocity to be made, as few countries seek to have individuals extradited from China.

There are both judicial and political precedents for the suspension of bilateral extradition treaties with China and Hong Kong. Moreover, according to article 62 (1, a) and b)) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, signed at Vienna on 23 May 1969, States may terminate and suspend the operation of Treaties when a fundamental [and unforeseeable] change of circumstances has occurred with regard to those existing at the time of the conclusion of a treaty, leading to a radical transformation in the extent of obligations still to be performed under the treaty.

In this regard, it is worth recalling the preamble to the Vienna Convention: "The State Parties to the present Convention […] noting that the principles of free consent and of good faith and the pacta sunt servanda rule are universally recognized, […] having in mind the principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United Nations, such as […] universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all.”

To all effects, the onus is on the Chinese authorities to reverse its abysmal trend of gross, flagrant and mass human rights violations by accepting and implementing the numerous recommendations made by UN Human Rights Procedures and other relevant bodies to ensure its judicial and penitentiary system is in line with universal human rights standards.

In the absence of such significant reforms, countries should suspend their bilateral extradition treaties with both China and Hong Kong as a matter of urgency.