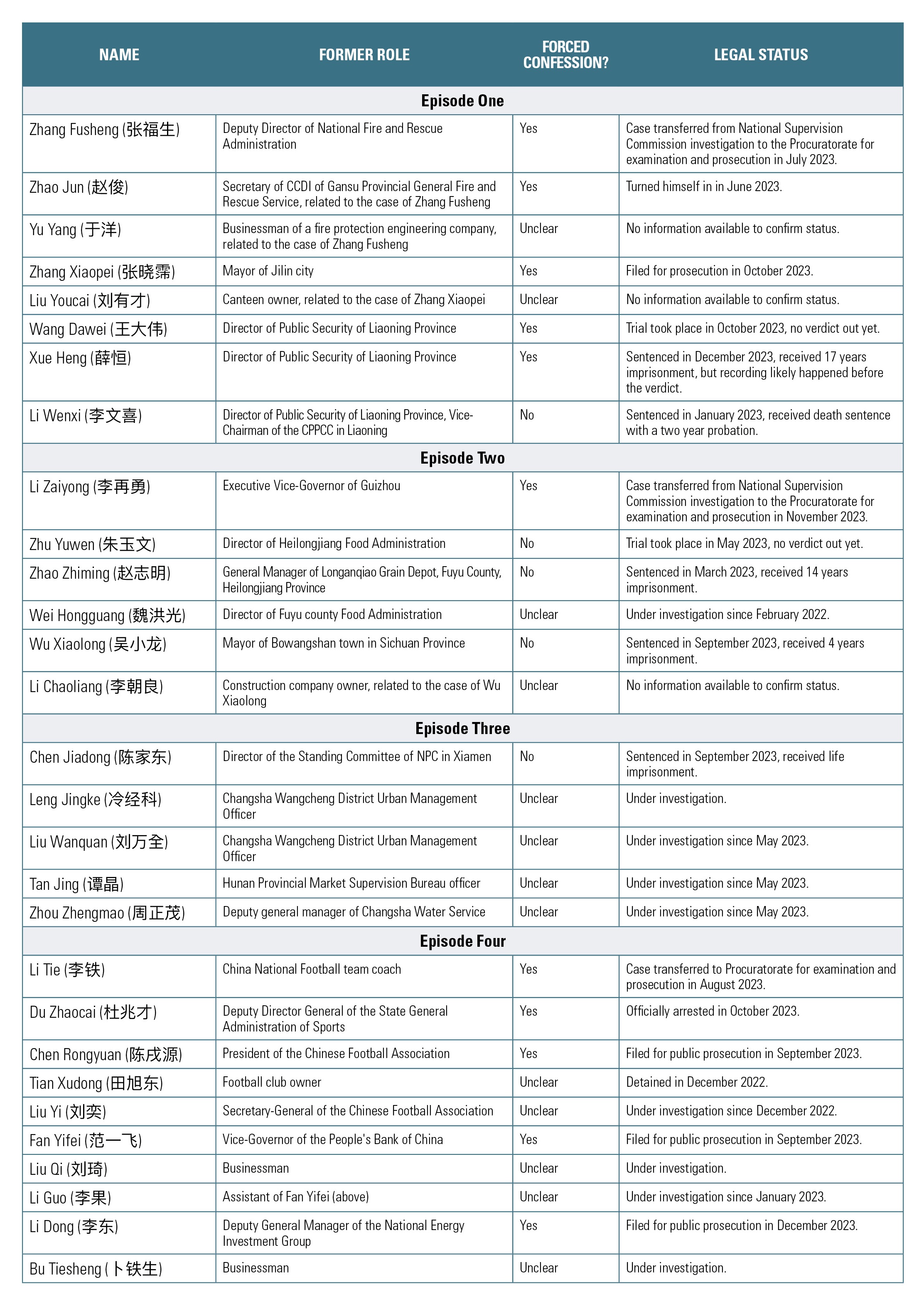

A total of 29* people in, or believed to be in, custody appeared to confess in the four-part series. Confessors ranged from former senior central government officials and provincial leaders, officials from State-affiliated organs, leaders of banking institutions, to people considered responsible for the current housing market situation, and people linked to the sporting industry. In fact, it was members of China's sporting industry that received the most attention, including many senior figures within its football industry. The (former) Chinese National Football team coach, Chen Xuyuan, who is in custody and still awaiting trial, was paraded and said (translation):

“The corruption in Chinese football does not only exist in certain individual areas – it’s everywhere, in each and every aspect”.

For most of them – 21 out of 29 - no known trial has taken place nor has any sentence been issued. This makes their appearances clear-cut forced TV confessions, matching CCTV’s prior and long-standing behaviour. Five of them have already been sentenced and transferred to prison, including one person who was sentenced to death. The status of three victims remain unclear, with no public information available on the status of their trial and/or sentence.

(*Many more appeared in confession-like performances, but are not detained or under criminal investigation, and are therefore not included in our mapping of targets here.)

The broadcast of this “documentary” and the confessions coincide with a reinvigorated mass campaign in the PRC to "clean up" the targeted industry sectors. It is not unusual for the State to use TV propaganda to bolster these recurring mass campaigns, as it did in January 2023. This connection is made all the more clear by the fact that this series was a joint production between CCTV and the Communist Party’s internal anti-corruption and discipline body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI).

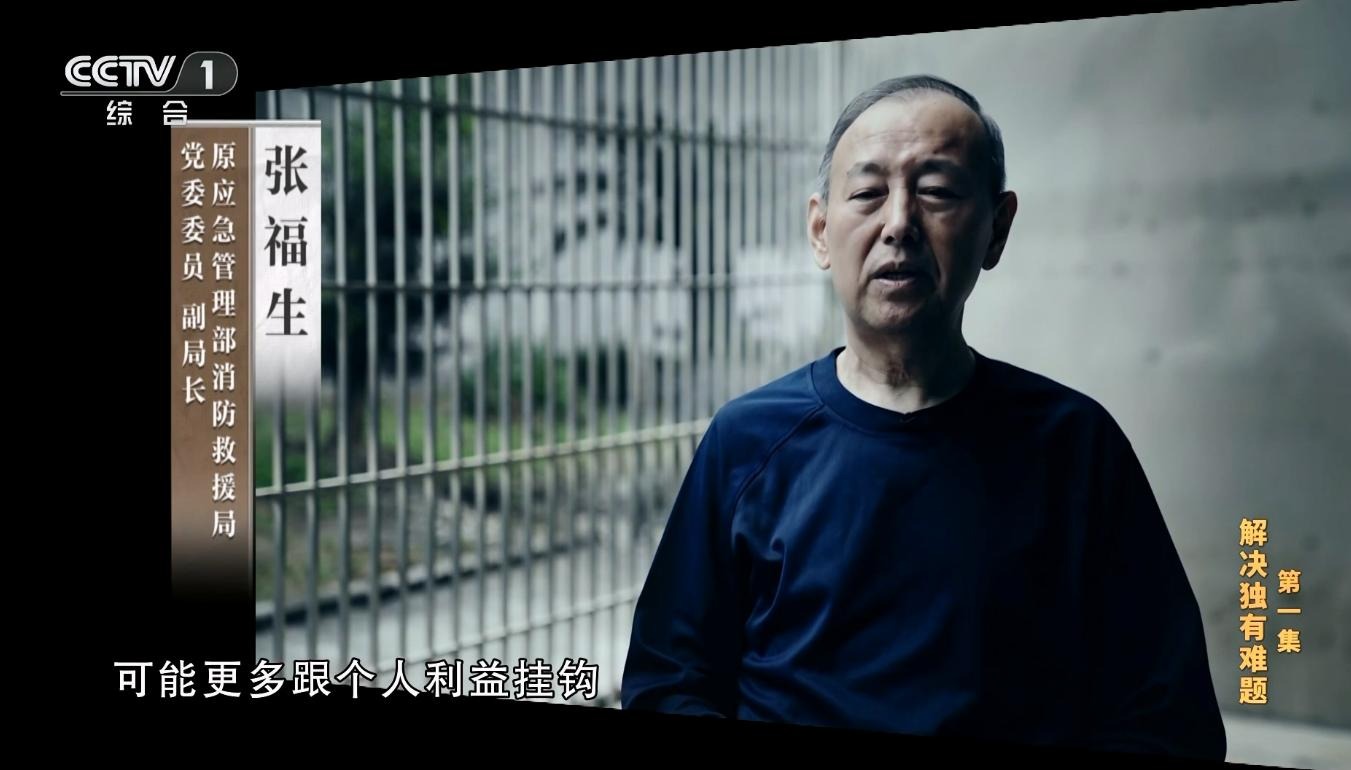

As in more traditional forced TV confessions of lawyers, journalists, and civil society figures, each of these broadcasts has one or a few main targets (main confessors), along with a number of supporting confessors to denounce the main confessors.

This is a well-established tool of political terror. As we have learned from the forced TV confession campaigns against lawyers, journalists, and NGO workers in the past decade, the main aim of these forced TV confessions is to parade a few individuals as examples to scare the larger community into towing the party line and to instill "discipline" and political loyalty into the wider industry/field. A few victims are used as tools to silence the larger community they represent.

As many observers have noted, “anti-corruption” work has taken up notably under Xi Jinping’s chairmanship of the Chinese Communist Party. It is often used - both domestically and abroad - as a guise to purge critical voices from within the establishment or bring entire sectors into line with the central party leadership.

Find the four episodes here: