China is using forced confession playbook for Uyghur propaganda videos

China is using the techniques of its now famous televised forced confessions to refute widespread global claims that it is persecuting Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

China is using the techniques of its now famous televised forced confessions to refute widespread global claims that it is persecuting Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

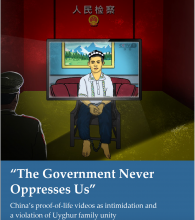

A new report out by US-based Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), The Government Never Oppresses Us, reveals how since February 2019, China’s Party-state media have broadcast at least 22 hostage-style “proof-of-life” (POL) videos of Uyghurs largely to dispute claims they are being kept in re-education camps or even that they are dead. They are a direct response to the political and media attention on the mass internment of Uyghurs and Kazakhs in re-education camps in Xinjiang since 2017 and to social media campaigns by Uyghurs overseas desperate to receive newss about their disappeared family members. Many were aired within just a few weeks of a public plea for information being made.

Using interviews and analyzing footage content, UHRP found credible evidence that, like the televised forced confessions (FCs) exposed in Safeguard Defenders’ Scripted and Staged, the individuals in these POL videos are coerced and told what to say.

They most closely resemble a particular type of televised FC that we called “Deny”; confessions that included statements that were an obvious response to criticism from overseas, for example, a denial that the victim had been tortured or kidnapped (when in fact the CCP had indeed tortured or kidnapped them).

Both televised forced confessions and POL videos are disinformation and lies. The truth is the very opposite of what the victims in these crude propaganda videos are forced to say. UHRP called them a “tool of misinformation, intimidation and fear”.

The fact that FCs and POL videos are so similar strengthens the argument that POL videos are not only fake news, but are a grievous abuse of human rights perpetrated by the CCP and all media that collude in their production and distribution.

POL videos violate international rights laws pertaining to the right to privacy and to family unity and prohibitions on degrading treatment. While these videos are also a clear attempt to frighten relatives overseas to stop their campaigning, UHRP argue that there are clear examples that campaigning has helped in individual cases and that demands on China to end this persecution should continue.

Safeguard Defenders has campaigned tirelessly to de-platform China’s Party-state media CGTN on grounds they have broadcast rights abusing forced confessions. Just a few weeks ago, our campaign got CGTN banned in the UK over an ownership regulation but also earlier convicted for airing FCs.

De-platforming such media is an important way to not only limit the audience for these videos but also to discourage the CCP from making them in the first place.

Key features of China's proof-of-life videos

-

Deny

“Our life here is great, our life is getting better and better.”

The greatest similarity between POL videos and FCs is they that are both denials. Overseas campaigners accuse China of persecuting Uyghurs, POL victims are on screen to claim that is not true. They claim they are free; others stress their financial stability – making unnatural references to savings and pension payments, presumably refuting accusations of forced labour.

-

Denounce

"Sayragul Sauytbay is a degenerate member of all women. She is a real scumbag!”

Both POL videos and FCs also have what UHRP calls “character assassinations”. The target of these in the POL vidoes is the relative overseas pleading for news of their family. The POL victim attacks their relative overseas, accusing them of rumour-mongering or worse. In FCs, many detainees were forced to smear and discredit the key target of the case, often accusing them of being morally degenerate or unprofessional. Notably, FCs would also include self-criticism.

-

Defend

"Now the country promotes many kinds of favourable policies, such as medical care for senior citizens.”

Both POL videos and FCs contain praise for the CCP and the authorities (called “defend” in Scripted and Staged). In POL videos, victims tend to focus on how the “motherland” has created wealth and stability in Xinjiang; in FCs, the victim talked about how helpful the police had been in handling their case and educating them as to the error of their ways.

-

Setting

POL videos often place the victim(s) in a carefully staged home setting, such as a living room but surrounded by Uyghur cultural objects – wall hangings, traditional rugs, and plates of Uyghur food as if to refute allegations that the government has been trying to eradicate the local culture. There are reports that China has ordered Uyghur households to Sinicize their homes. In FCs, victims were either shown in civilian clothes, even though they were detainees, or portrayed as criminals with prison garb, shaved heads and bars, even though they had not been convicted in a court of law.

-

‘Normalcy’

“I work eight hours now every day. My salary is 2,000 to 2,500 yuan a month. During my spare time I like to play basketball. I also like to have dinner with my girlfriend. We have known each other for four or five years. Yesterday we got married.”

Some victims reel off a list of unrelated statements, which the UHRP report argues is an attempt to prove the victim is leading a normal life, and not interred in a re-education camp. In China’s televised FCs, many victims did not discuss the alleged crime – indeed, many of the rights defenders had committed no crime – but rather issues unrelated to why they were being arbitrarily detained.

-

Warning

“Don’t be deceived by overseas anti-China forces again and stop saying those things.”

Victims in POL videos appealed to their relatives to stop campaigning. Similarly, televised FCs contained “warnings” to others to avoid copying their example of “colluding with anti-China forces.”

-

Ill health

Several of the POL victims looked visibly unwell, possibly the result of being mistreated in a re-education camp or forced labour programme. Some had “dark circles underneath eyes, explicitly declared health problems, and an inability to stand straight or walk freely.” In several FCs, victims looked unwell, most notably Swedish publisher Gui Minhai who had visibly lost several teeth since he was last seen free.

Background

There is ample evidence that since 2017 China has forcibly detained at least 1 million Uyghurs and Kazakhs into re-education camps in Xinjiang, where grave human rights abuses have taken place including rape, forced sterilisations and beatings. There is also evidence that many have also been drafted into forced labour. Some critics have argued that this constitutes genocide of an ethnic group. Since China does not allow outside observers to freely travel in Xinjiang and it does not provide any credible data on its re-education or labour programmes, there is no way to assess the true extent of the human rights atrocities taking place in Xinjiang today.

As family members disappeared, many relatives overseas took part in global campaigns demanding China prove that their loved ones were still alive using hashtags like #StillNoInfo and #ShowThemAll. The POL videos are China’s propaganda response.