中国维权人士在老挝失踪,恐被绑架

在6月4日天安门大屠杀纪念日的前几天,流亡的36岁中国评论家杨泽伟(又名乔鑫鑫),从他位于老挝的首都万象的家中消失了。据他的一位邻居说,六名中国警察和两名老挝警察搜查了他的家。从那时起,他就失踪了。

无独有偶,几周前一名中国活动家疑似在蒙古遭绑架。

这篇关于杨泽伟失踪的文章在撰写时获得以下提到的人的协助,并将随着更多信息的出现会再次更新。

杨泽伟和 “拆墙运动”

杨泽伟持有老挝的居留证并曾是自由亚洲电台的记者。他创办了“拆墙运动”(英文Ban the Great Firewall或BanGFW)(推特号链接在这),同时也与一些人共同撰写了一本突破中共互联网防火墙的指南。

杨泽伟与居住在东南亚、美国、加拿大和荷兰的流亡中国活动家和志愿者组成的小团队合作,帮助中国境内的人们规避中国政府的互联网防火墙,并倡导中国结束审查制度。在今年头四个月,他们就举行了许多活动,如发表公开信和在中国驻洛杉矶领事馆外举行街头抗议活动。

来自中国的压力不断增加

杨泽伟有足够的理由担心他可能会被失踪。

今年4月,他的哥哥给他发信息,告诉他中国当局正在骚扰和威胁杨泽伟仍在中国的家人。

他的哥哥要求他停止他的活动,同时听起来很绝望。

他的哥哥要求他停止他的活动,同时听起来很绝望。

杨泽伟在4月初将他哥哥的信息截图发到了推特上,原文如下:

「你也老大不小了,做事能不能考虑一下父母,他们六七十岁的人了。还要为你担心」

「说句不好听的,他们活一天选一天的人,不指望你孝敬他们,但是也不要给他们惹麻烦」

「做事情想想后果,想想你年迈的父母。」

「现在大数据时代,什么都能查到,什么都能监控到,你不要以为你在国外就安全,你家里还有你的父母,想想他们。」

作为一个活跃的推特用户,杨泽伟精通英语(他以前曾教英语)和其他语言,而且是单身,他全心全意投入到他的倡议工作中。他应该很清楚其他活动人士的亲友在中国受到中国当局的威胁,以及当这些威胁不起作用时,倡议者本人也可能在东南亚被绑架的故事。他应该也知道该地区的地方政府如何经常与中国警方合作,将目标人物任意拘留并非法遣送回中国。他的居留证实质上不能保证他的人身安全。

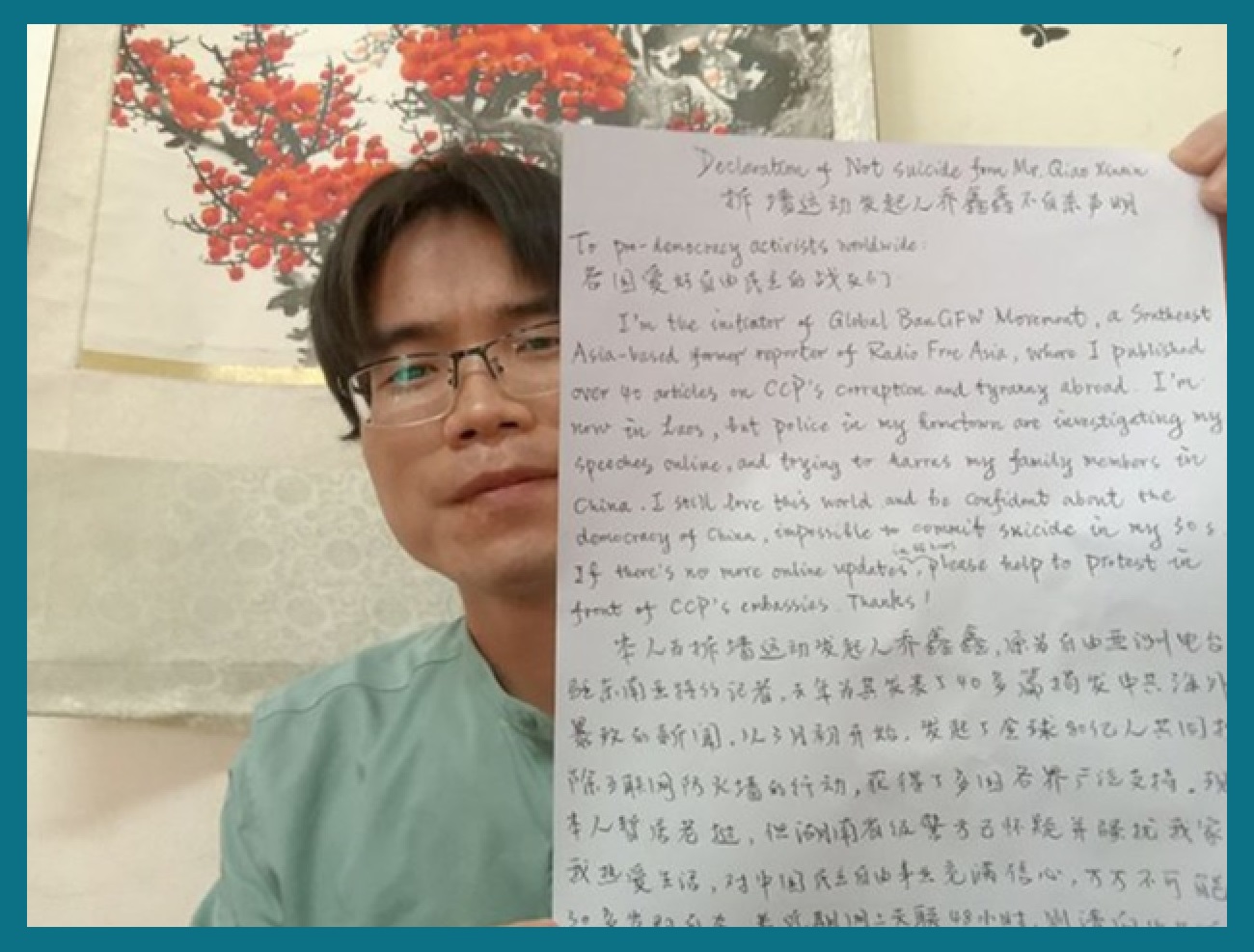

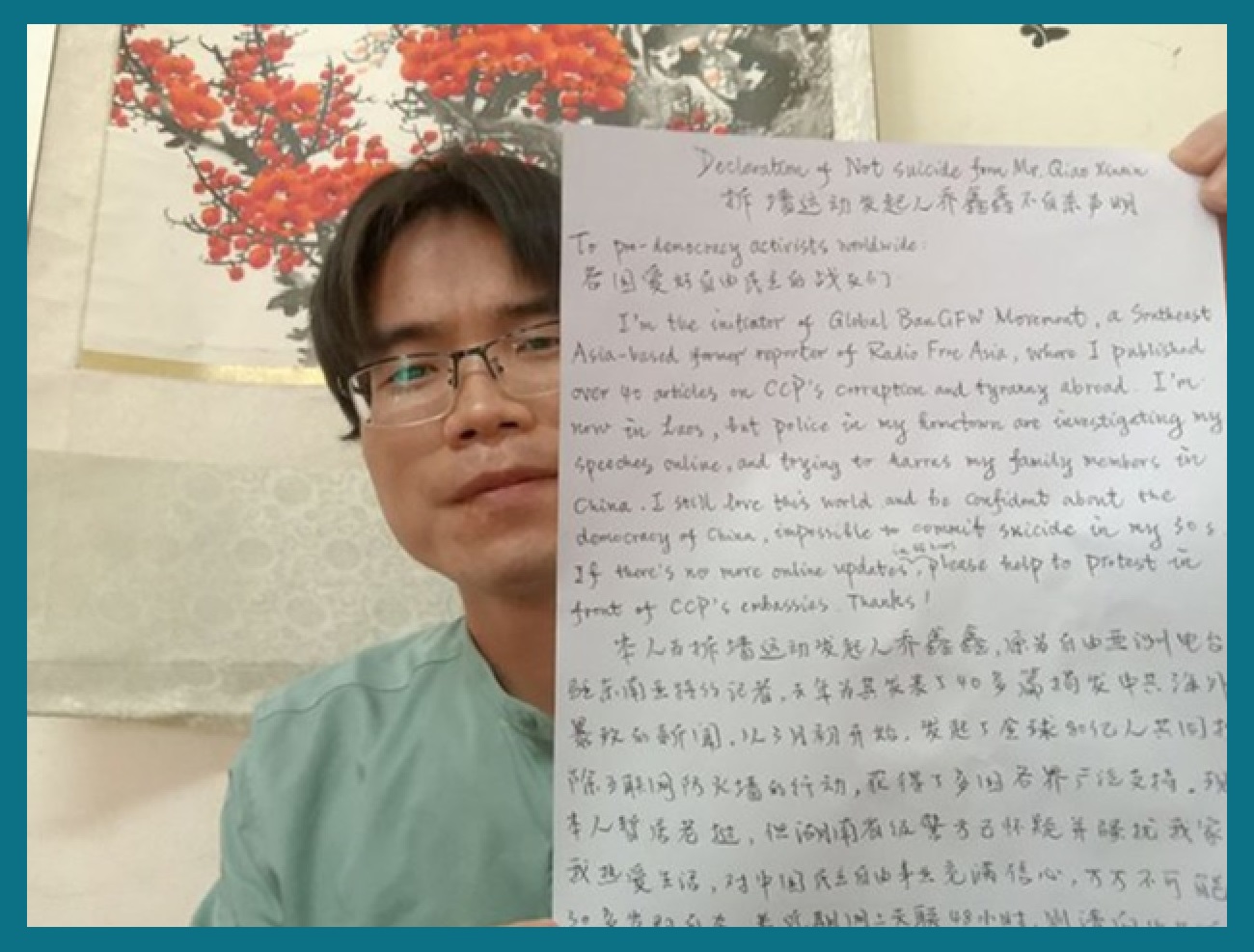

面对这些恐惧,4月20日,杨泽伟发表了两天前写的 "不自杀的声明"。他写道:

「我热爱生活,对中国民主自由事业充满信心,万万不可能在30多岁即自杀。若近期间失联48小时,则请向中共追责。」

杨泽伟消失了

杨泽伟每天都会通过不同的管道与拆墙运动的伙伴联络。早前,他曾告知群里的成员盛雪(加拿大),王清鹏(美国)和林生亮(荷兰),如果他失踪超过48小时,请他们转发他的声明 。

5月28日,杨泽伟去了万象的唐人街为该运动搜集资料。第二天,他发现自己的手机号码无法使用,于是他发了一条信息,说他要出去买一张新的电话卡。

直到6月2日,他的朋友们才意识到,他已经48小时没有在推特上发文,也没有在电报上给任何一个人发信息,或者在他们的各种聊天组中更新。根据王清鹏所说,最后一次有人注意到到杨泽伟的在线时间是5月31日下午5点56分。

拆墙运动的成员推测,杨泽伟可能是在5月31日星期三晚上7点以后被带走的。他的习惯是每天去游泳;也曾提到在下午6点前去游泳,很大可能在晚上7点左右回家,因为此后,天就黑了。

同日,他们请住在附近的一名志愿者白(化名)去杨泽伟的家中看看。

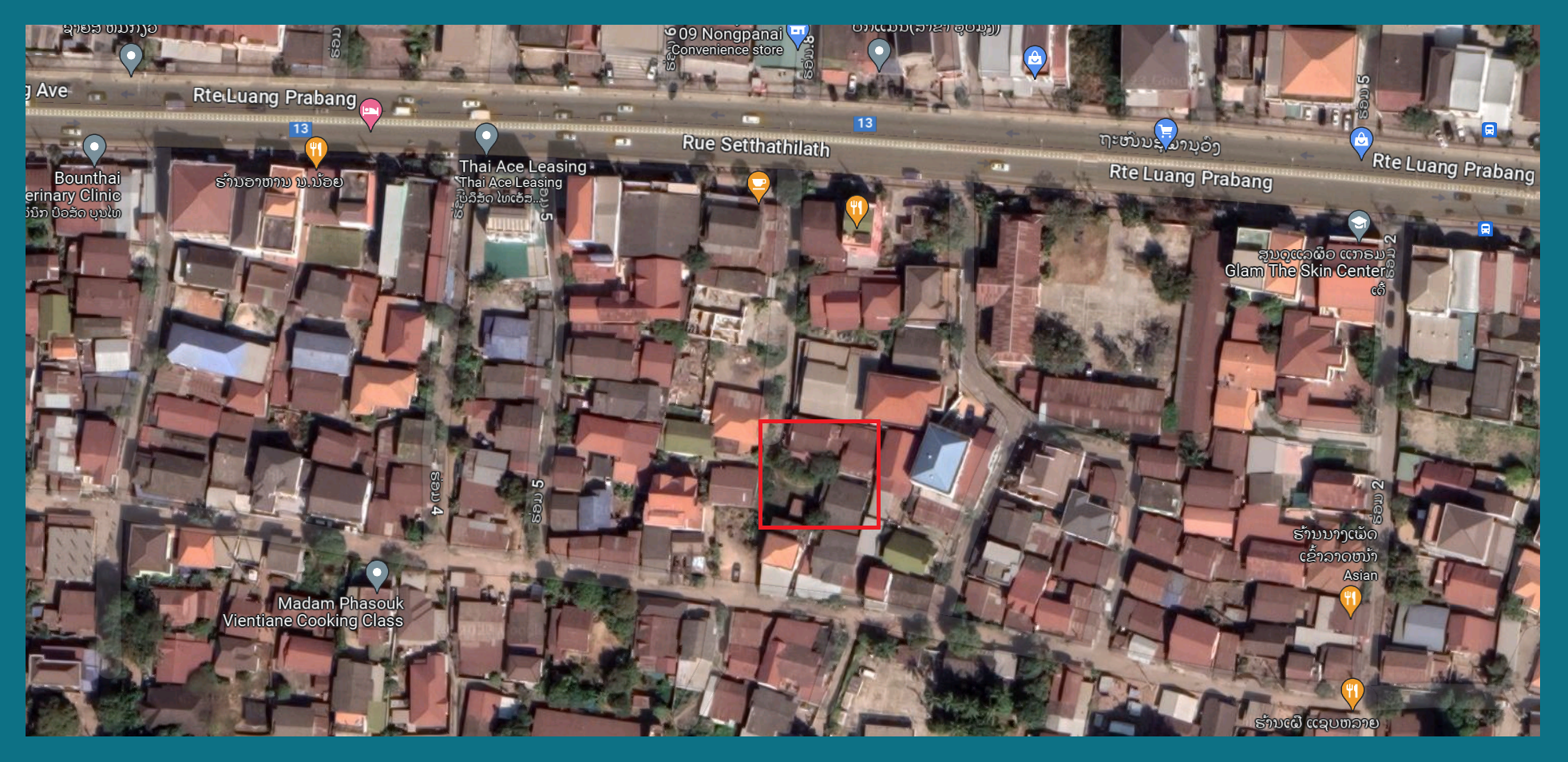

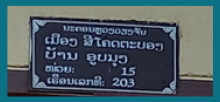

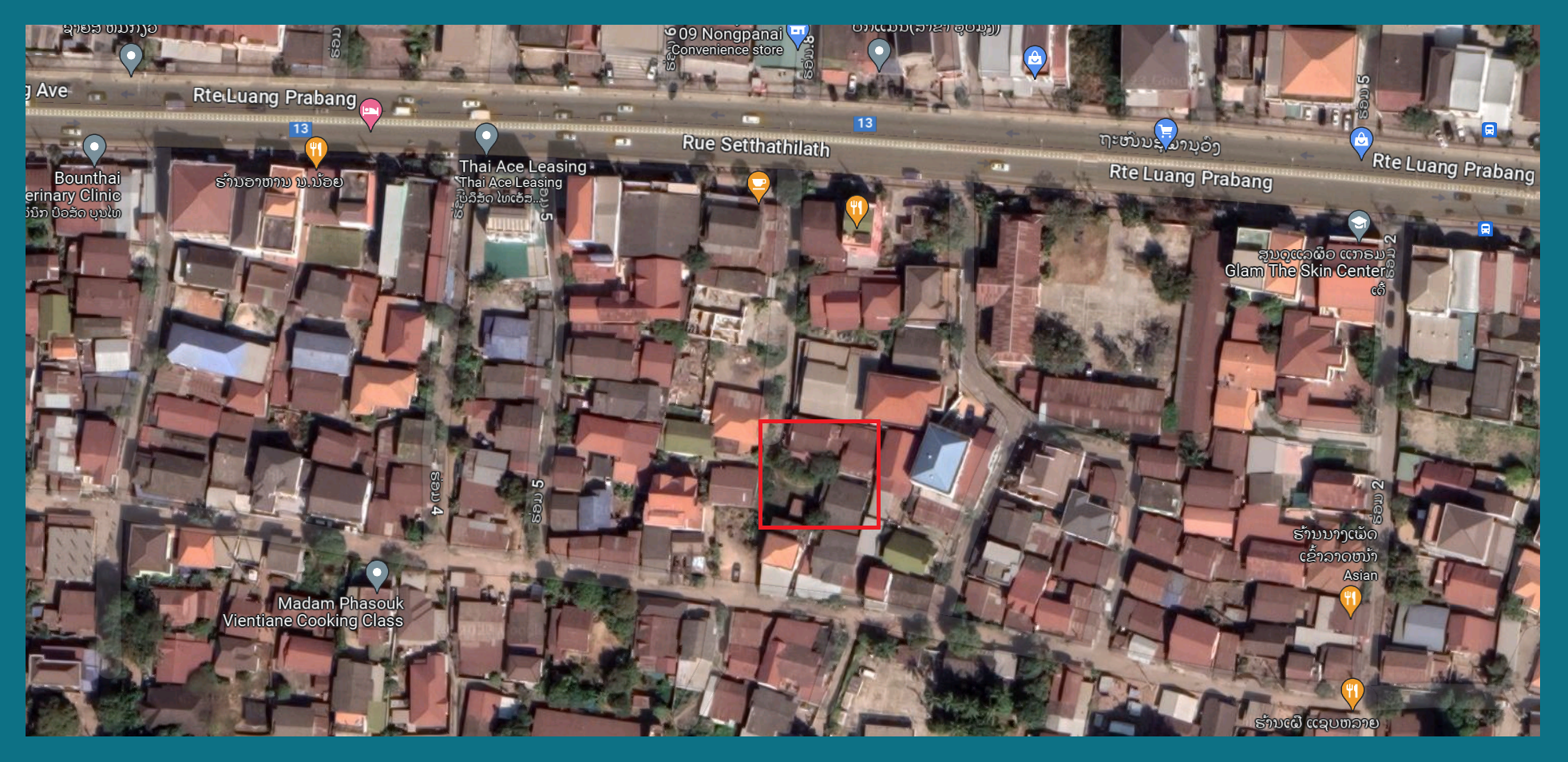

当白开车到达那里时,已经是6月3日凌晨1点了,他立刻发现了一些奇怪的迹象。通常情况下,杨泽伟的家附近不会有汽车,但白却发现两辆大型黑色休旅车停在街道“Rue Setthathilath” 的对面,这街道是连接杨泽伟居住的巷子的主要道路。

白拿着手电筒走到杨泽伟在巷子最里面的黑灯瞎火的住所,却突然发现有人在盯着他。他吓了一跳,马上跑回车上开车逃离现场。随后发现有一辆摩托车和一辆汽车紧紧尾随他。不久,他认为自己已经甩掉了这些人,便开车回家。深夜2点左右,在他回家后不久,有三个人来到他的院子里,向他的窗户窥视。白不敢開灯,静候他们离开。當他们一走,白马上收拾细软,辗转逃离老挝。

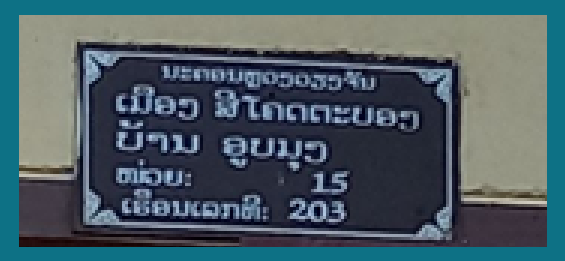

拆墙运动的成员后来又找到另一名志愿者在6月3日寻找杨泽伟的下落。子洋(化名)到达时发现杨泽伟的家门是锁着的。他使用谷歌翻译与老挝邻居沟通后得悉他们最担心的事情已经发生。几天前,这位邻居看到两名老挝警察和六名中国警察来到杨泽伟的家里,随后他被戴上手铐押走。

拆墙运动的成员后来又找到另一名志愿者在6月3日寻找杨泽伟的下落。子洋(化名)到达时发现杨泽伟的家门是锁着的。他使用谷歌翻译与老挝邻居沟通后得悉他们最担心的事情已经发生。几天前,这位邻居看到两名老挝警察和六名中国警察来到杨泽伟的家里,随后他被戴上手铐押走。

子洋在第二天,也就是6月4日再次返回杨泽伟家。

他发现杨的房子正在进行装修工作,但房东不在。有一些杨泽伟的物品被堆在外面的一张桌子上。但子洋没有看到任何电话或电脑,不过这些装置几乎可以肯定是在警方突击检查中被没收了。

子洋确信他看到了房子其中一面墙上有血溅痕跡,并拍了一张照片。但从他拍的照片中很难确定那是否真的是血。和白一样,子洋也感到恐惧便也逃离了这个国家。

中国警方承认参与其中

正当当地志愿者在万象寻找蛛丝马迹时,林生亮开始给杨泽伟老家湖南省衡阳市灵官镇的警察打电话。相当明智的是,林生亮记录了所有这些对话,可以在他的推特上看到。

他打电话给灵官镇当地的警方、国保大隊和当地纪律检查委员会的书记(这个由中国共产党管理的反贪腐机构也是中国的长臂警察行动“天网”及其子行动“猎狐行动”的管理机关)。他们都不承认参与其中,但灵官镇警方在林的反复追问下,最终表示他们没有参与其中,此案正由一个专案组处理。

这证实了有关杨泽伟的执法行动确实存在,但这是指当地针对杨泽伟家人的行动,还是在老挝的执法行动还不清楚。不管怎么说,根据他们的说词警方肯定在追捕他。

这类型的行动已经不是第一次了。这篇详细的文章記錄了中國警方吹噓派警察在异国他乡抓人,包括老挝。文章非常详细地描述了从中国策划到在老挝抓捕常国华和万慧君的实际操作。

老挝政府仍旧保持沉默

到目前为止,所有向老挝政府、老挝驻华盛顿特区大使馆和常驻联合国日内瓦办事处的代表团提交的询问都没有得到答复。

6月12日,美国国务院发言人谴责中国当局对活动人士的威胁、骚扰和越境绑架。在媒体报导乔鑫鑫[杨泽伟的别名]的失踪后,发言人亦表示关切杨的安全。

跨界执法、跨境镇压和非自愿回国

保护卫士早前关于《非自愿回国》的报告,揭露了许多在合法的司法渠道之外采用各种方法将个人送回中国的案例。这些方法包括威胁目标在中国的家人,由中国特工骚扰或恐吓在海外居住国的目标,以及在通常专制的东道国政府的支持下直接绑架和非法跨境执法。

保护卫士早前关于《非自愿回国》的报告,揭露了许多在合法的司法渠道之外采用各种方法将个人送回中国的案例。这些方法包括威胁目标在中国的家人,由中国特工骚扰或恐吓在海外居住国的目标,以及在通常专制的东道国政府的支持下直接绑架和非法跨境执法。

保护卫士目前仍正在追踪调查东南亚地区的其他一些案件(老挝11起,越南4起,泰国9起,缅甸4起),包括王炳章、李新、彭明、桂民海、姜野飞、董广平等。

Yang had good reason to be worried he might be disappeared.

In April this year, his brother messaged him to tell him that Chinese authorities were harassing and threatening their family back in China.

He asked him to stop his activism and sounded desperate.

He asked him to stop his activism and sounded desperate.

Yang posted a screenshot of his brother’s messages in early April to Twitter (translation by Safeguard Defenders).

“You’re not a young kid anymore. Can’t you think about our parents before you do something? They’re already in their 60s and 70s, and they still need to worry about you.”

“I’m going to tell you something you won’t like. They’re living one day at a time. They’re not expecting you to be filial, just not to get them into trouble.”

“Think about the consequences before you doing something. Think about our elderly parents.”

“This is the era of big data, everything can be traced, everything can be monitored. Don’t think you’re safe just because you’re overseas. Your parents are still living at home, think about them.”

As an active Twitter user, with a good command of English (he had previously taught English) among other languages, and single, Yang threw himself into his activism work. He would have been acutely aware of reports of other activists’ families being threatened by Chinese authorities in China, as well as stories of kidnappings of the activists themselves in Southeast Asia when those threats failed to work. He was also likely aware of how local governments in the region often collaborated with Chinese police to have targets detained and illegally deported back to China. His visa would be no protection.

Facing these fears, on 20 April Yang published a “declaration to not commit suicide”, written two days earlier. He wrote:

“I still love this world… impossible to commit suicide in my 30s. If there’s no more online updates in 48 hours, please help to protest in front of CCP’s embassies.”

Yang communicated with BanGFW members daily on a variety of platforms. He had earlier asked group members Sheng Xue in Canada, Wang Qingpeng in the US, and Lin ‘James’ Shengliang in the Netherlands to republish that letter if he went missing for more than 48 hours.

On 28 May, Yang went to Vientiane’s Chinatown to do some work for the group. The next day, he found that his phone number was not working so he sent a message saying he was going out to buy a new SIM card.

It wasn’t until 2 June that his friends realized it had been 48 hours since he had posted on Twitter or messaged any of them on Telegram, or in any of their various chat groups. According to Wang Qingpeng, the last anyone saw of Yang online was 17:56 on May 31.

The group worked out that he had probably been taken sometime after 7pm on Wednesday, 31 May. It was Yang’s custom to go for a daily swim, which he had mentioned just before 6pm, likely returning home around 7pm. After that it went dark.

That same day, they asked one of their volunteers, Bai (not his real name), who lived nearby, to go to Yang’s home.

When Bai arrived there after a short ride in his car it was already 1am on 3 June, and he immediately noticed something was odd. Normally, there were no cars around Yang’s home, but Bai spotted two large black SUVs parked on the opposite side of Rue Setthathilath, the main road at the entrance of the alley where Yang lived.

Bai walked to Yang’s unlit residence in the far back of the alleyway using a flashlight and noticed someone staring at him. Startled, he ran back, got in his car, and sped away. He was followed closely by a motorbike and a car. Thinking he had shaken them off, he drove home. Around 2pm, not long after he had got home, three people came into his yard and peered into his window. He kept the lights off and waited. As soon as they had left, Bai packed his belongings and not long after fled the country.

The group asked another volunteer to look for Yang on 3 June. Ziyang (not his real name) found Yang’s door locked when he arrived. Using Google translate to help communicate with the Laotian neighbour, he found out that their worst fears had come true. The neighbour had seen two Laotian and six Chinese police officers come to Yang’s house, handcuff him and take him away a few days previously.

Ziyang returned the next day, June 4.

He found renovation work being done on Yang’s house but the landlord was not around. At least some of Yang’s possessions had been piled up outside on a table. Ziyang couldn’t see any phone or computer. They were almost certainly confiscated during the raid.

Ziyang is convinced he saw blood splatter on one of the walls and took a photo. It is hard to tell definitively if it is indeed blood from the photo he took. Like Bai, Ziyang felt scared and he fled the country too.

While local volunteers were finding out what they could in Vientiane, Lin started calling the police in Yang’s hometown in Lingguan Town, Hengyang City in Hunan province. Wisely, Lin recorded all these conversations, held on June 6, 7 and 8, available on his twitter feed.

He called the local Lingguan police, the national security unit of the PSB and the local Discipline Inspection Commission - the Party-run anti-corruption body that also overseas China’s long-arm policing operations known as Sky Net (and its sub-operation Fox Hunt). None of them admitted involvement but the Lingguan police, when pressed repeatedly finally said no, it was not involved, this case is being handled by a special task force.

This corroborates that a policing operation was indeed in place regarding Yang, but whether it refers to local operations against his family, or the policing operation in Laos is unclear. Regardless, police was most certainly after him, now admitted by themselves.

It wouldn't be the first time. In this detailed post (Chinese only), Chinese police brag about sending police officers to catch people, including in Laos, where they then targeted Chang Guohua and Wan Huijun, and they describe in great detail the practical operation, from planning in China to execution in Laos.

Laotian government remains silent

Inquiries to the government, the Laotian embassy in Washington DC, and its permanent mission to the UN in Geneva have all gone unanswered.

On 12 June, a US State Department spokesperson “condemned threats, harassment and cross-border abductions of activists by the Chinese authorities, saying there were concerns for Qiao’s [Yang’s] safety following media reports of his disappearance.”

Safeguard Defenders’ report on Involuntary returns, exposed numerous cases where a combination of methods are employed to return individuals to China outside of judicial channels. These include threats against family in China, harassment or intimidation of targets in host countries by Chinese agents, as well as a direct kidnappings and illegal policing actions with the support of usually authoritarian host governments.

Safeguard Defenders’ report on Involuntary returns, exposed numerous cases where a combination of methods are employed to return individuals to China outside of judicial channels. These include threats against family in China, harassment or intimidation of targets in host countries by Chinese agents, as well as a direct kidnappings and illegal policing actions with the support of usually authoritarian host governments.

Safeguard Defenders is currently tracking a number of other cases in the region (11 in Laos, four in Vietnam, nine in Thailand, and four in Myanmar), including for example Wang Bingzhang, Li Xin, Peng Ming, Gui Minhai, Jiang Yefei, and Dong Guangping.