Disappearance of Chinese critic in Laos, feared kidnapped

A few days before June 4, the anniversary of the Tiananmen massacre, exiled Chinese critic Yang Zewei (杨泽伟), also known as Qiao Xinxin (乔鑫鑫), 36, disappeared from his home in Laos’s sleepy capital of Vientiane. According to a neighbour, six Chinese and two Laotian police officers raided his home.

He has been missing since then.

This happened just a few weeks after a similar suspected kidnapping of a Chinese activist took place in Mongolia.

This report on Yang’s disappearance was written with the help of the people named and/or referenced below.

It will be updated as more information is made available.

Yang and ‘Ban the Great Firewall’ movement

Yang was in Laos on a residence permit and had been a reporter for Radio Free Asia. He founded the Ban the Great Firewall (BanGFW) (Twitter account here), and was a co-author of a handbook on how to fight the Great Firewall.

Yang worked with a small team of exiled Chinese activists and volunteers who lived in Southeast Asia, the US, Canada and the Netherlands to help people inside China circumvent the great firewall and to advocate for China to end its censorship. In just the first four months of the year they had held many activities, such as publishing open letters and holding a street protest outside the Chinese Consulate in Los Angeles.

Yang had good reason to be worried he might be disappeared.

In April this year, his brother messaged him to tell him that Chinese authorities were harassing and threatening their family back in China.

He asked him to stop his activism and sounded desperate.

He asked him to stop his activism and sounded desperate.

Yang posted a screenshot of his brother’s messages in early April to Twitter (translation by Safeguard Defenders).

“You’re not a young kid anymore. Can’t you think about our parents before you do something? They’re already in their 60s and 70s, and they still need to worry about you.”

“I’m going to tell you something you won’t like. They’re living one day at a time. They’re not expecting you to be filial, just not to get them into trouble.”

“Think about the consequences before you doing something. Think about our elderly parents.”

“This is the era of big data, everything can be traced, everything can be monitored. Don’t think you’re safe just because you’re overseas. Your parents are still living at home, think about them.”

As an active Twitter user, with a good command of English (he had previously taught English) among other languages, and single, Yang threw himself into his activism work. He would have been acutely aware of reports of other activists’ families being threatened by Chinese authorities in China, as well as stories of kidnappings of the activists themselves in Southeast Asia when those threats failed to work. He was also likely aware of how local governments in the region often collaborated with Chinese police to have targets detained and illegally deported back to China. His visa would be no protection.

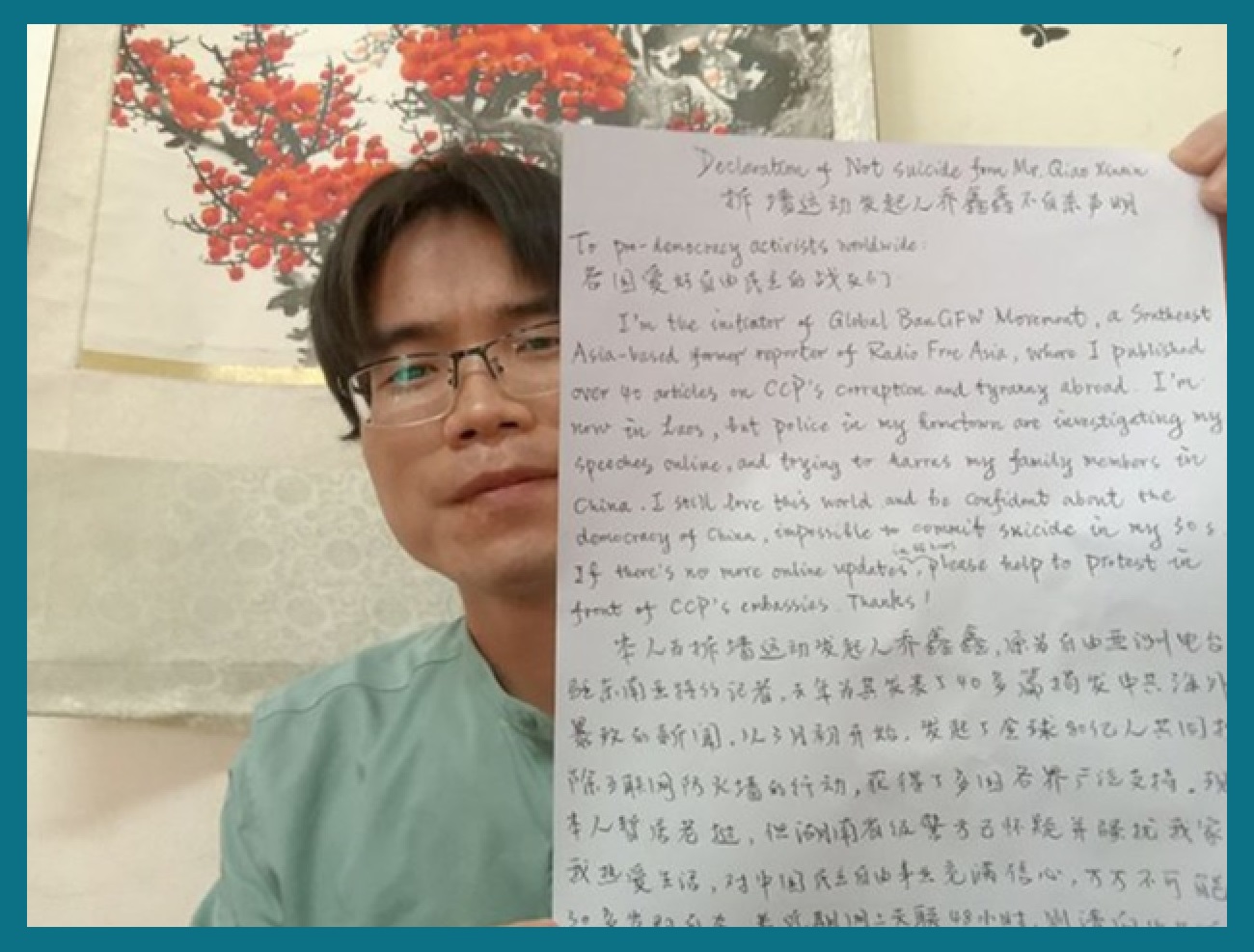

Facing these fears, on 20 April Yang published a “declaration to not commit suicide”, written two days earlier. He wrote:

“I still love this world… impossible to commit suicide in my 30s. If there’s no more online updates in 48 hours, please help to protest in front of CCP’s embassies.”

Yang communicated with BanGFW members daily on a variety of platforms. He had earlier asked group members Sheng Xue in Canada, Wang Qingpeng in the US, and Lin ‘James’ Shengliang in the Netherlands to republish that letter if he went missing for more than 48 hours.

On 28 May, Yang went to Vientiane’s Chinatown to do some work for the group. The next day, he found that his phone number was not working so he sent a message saying he was going out to buy a new SIM card.

It wasn’t until 2 June that his friends realized it had been 48 hours since he had posted on Twitter or messaged any of them on Telegram, or in any of their various chat groups. According to Wang Qingpeng, the last anyone saw of Yang online was 17:56 on May 31.

The group worked out that he had probably been taken sometime after 7pm on Wednesday, 31 May. It was Yang’s custom to go for a daily swim, which he had mentioned just before 6pm, likely returning home around 7pm. After that it went dark.

That same day, they asked one of their volunteers, Bai (not his real name), who lived nearby, to go to Yang’s home.

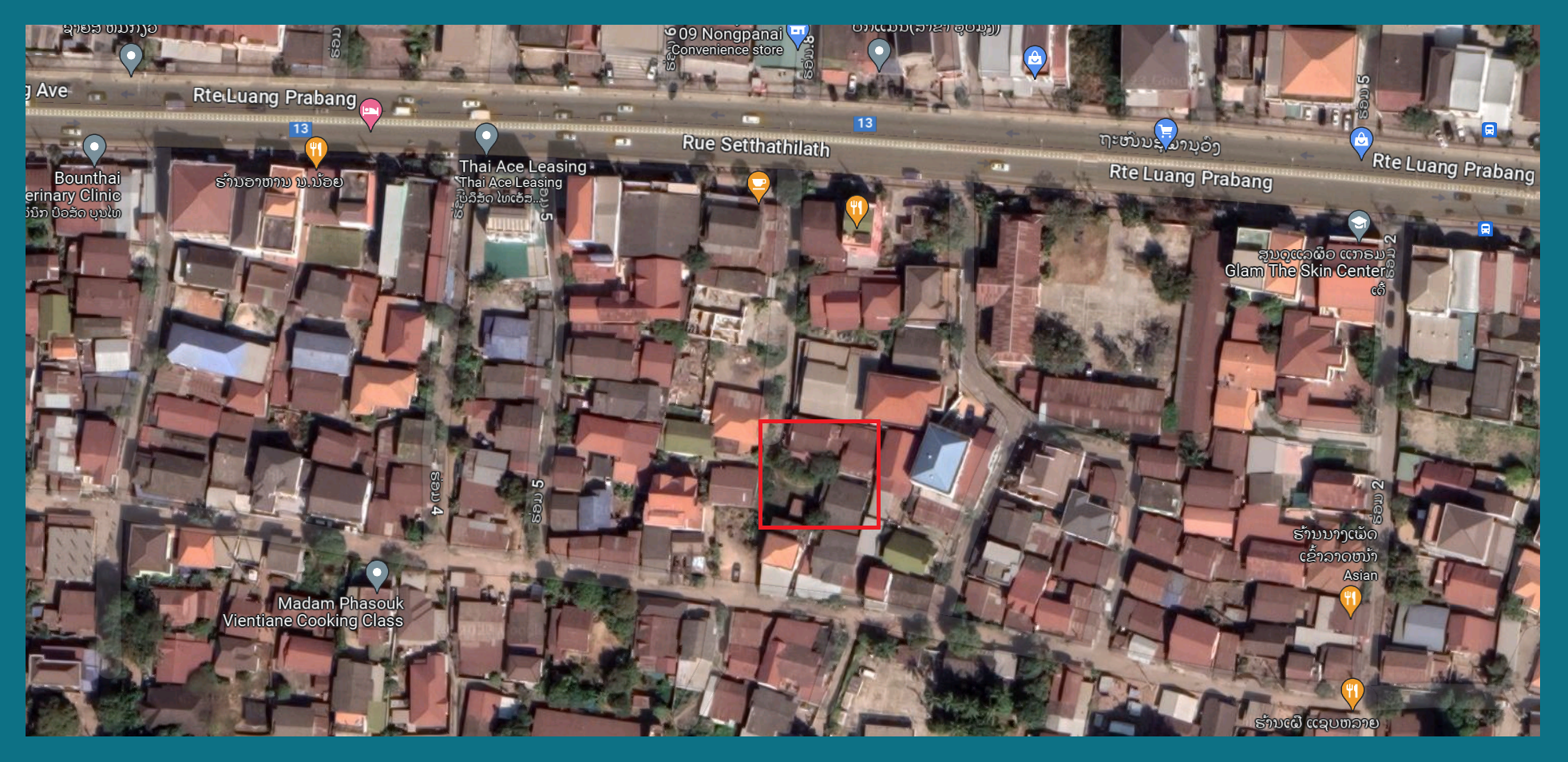

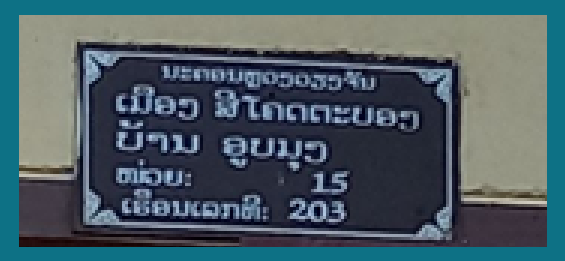

When Bai arrived there after a short ride in his car it was already 1am on 3 June, and he immediately noticed something was odd. Normally, there were no cars around Yang’s home, but Bai spotted two large black SUVs parked on the opposite side of Rue Setthathilath, the main road at the entrance of the alley where Yang lived.

Bai walked to Yang’s unlit residence in the far back of the alleyway using a flashlight and noticed someone staring at him. Startled, he ran back, got in his car, and sped away. He was followed closely by a motorbike and a car. Thinking he had shaken them off, he drove home. Around 2pm, not long after he had got home, three people came into his yard and peered into his window. He kept the lights off and waited. As soon as they had left, Bai packed his belongings and not long after fled the country.

The group asked another volunteer to look for Yang on 3 June. Ziyang (not his real name) found Yang’s door locked when he arrived. Using Google translate to help communicate with the Laotian neighbour, he found out that their worst fears had come true. The neighbour had seen two Laotian and six Chinese police officers come to Yang’s house, handcuff him and take him away a few days previously.

Ziyang returned the next day, June 4.

He found renovation work being done on Yang’s house but the landlord was not around. At least some of Yang’s possessions had been piled up outside on a table. Ziyang couldn’t see any phone or computer. They were almost certainly confiscated during the raid.

Ziyang is convinced he saw blood splatter on one of the walls and took a photo. It is hard to tell definitively if it is indeed blood from the photo he took. Like Bai, Ziyang felt scared and he fled the country too.

While local volunteers were finding out what they could in Vientiane, Lin started calling the police in Yang’s hometown in Lingguan Town, Hengyang City in Hunan province. Wisely, Lin recorded all these conversations, held on June 6, 7 and 8, available on his twitter feed.

He called the local Lingguan police, the national security unit of the PSB and the local Discipline Inspection Commission - the Party-run anti-corruption body that also overseas China’s long-arm policing operations known as Sky Net (and its sub-operation Fox Hunt). None of them admitted involvement but the Lingguan police, when pressed repeatedly finally said no, it was not involved, this case is being handled by a special task force.

This corroborates that a policing operation was indeed in place regarding Yang, but whether it refers to local operations against his family, or the policing operation in Laos is unclear. Regardless, police was most certainly after him, now admitted by themselves.

It wouldn't be the first time. In this detailed post (Chinese only), Chinese police brag about sending police officers to catch people, including in Laos, where they then targeted Chang Guohua and Wan Huijun, and they describe in great detail the practical operation, from planning in China to execution in Laos.

Laotian government remains silent

Inquiries to the government, the Laotian embassy in Washington DC, and its permanent mission to the UN in Geneva have all gone unanswered.

On 12 June, a US State Department spokesperson “condemned threats, harassment and cross-border abductions of activists by the Chinese authorities, saying there were concerns for Qiao’s [Yang’s] safety following media reports of his disappearance.”

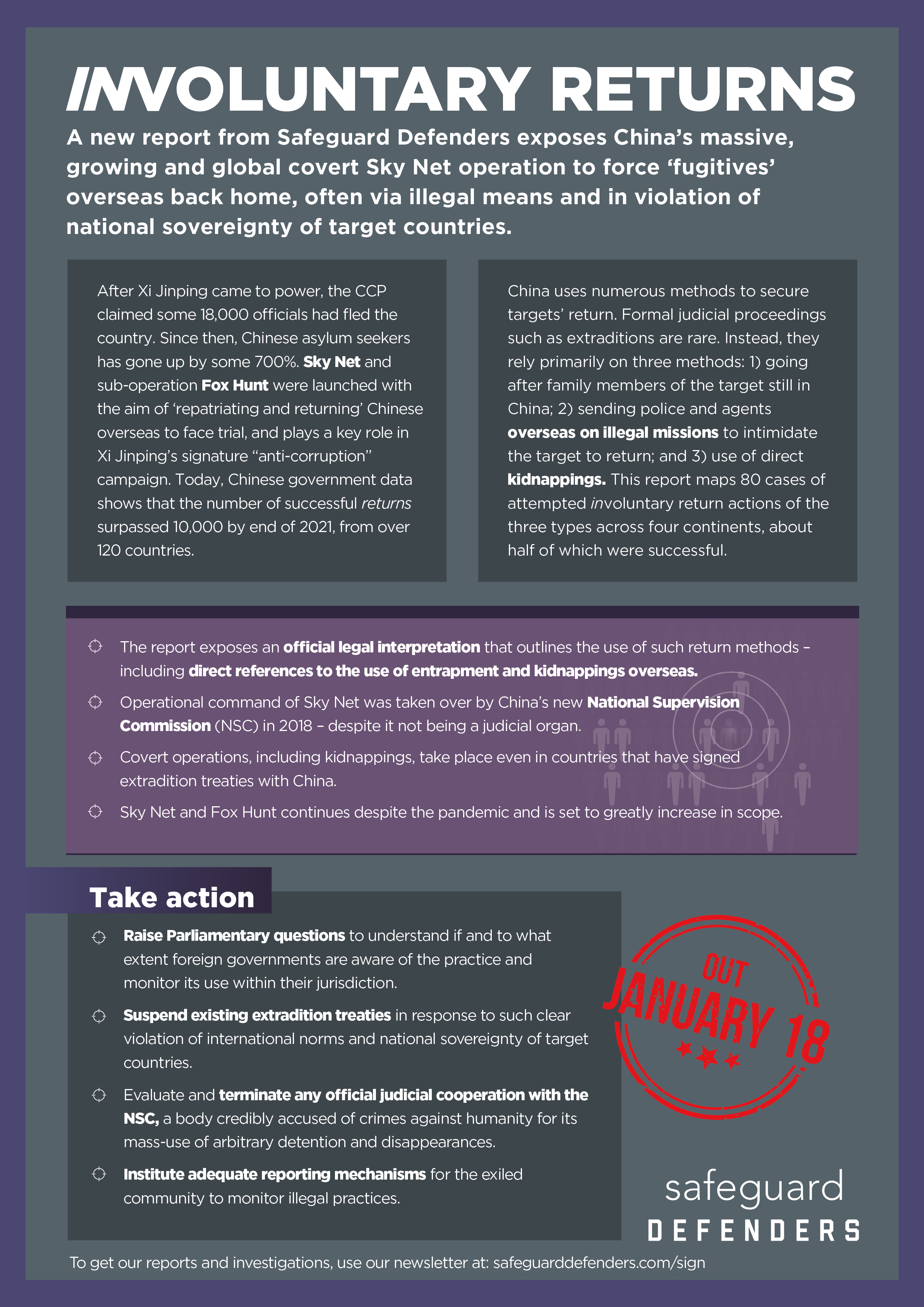

Safeguard Defenders’ report on Involuntary returns, exposed numerous cases where a combination of methods are employed to return individuals to China outside of judicial channels. These include threats against family in China, harassment or intimidation of targets in host countries by Chinese agents, as well as a direct kidnappings and illegal policing actions with the support of usually authoritarian host governments.

Safeguard Defenders’ report on Involuntary returns, exposed numerous cases where a combination of methods are employed to return individuals to China outside of judicial channels. These include threats against family in China, harassment or intimidation of targets in host countries by Chinese agents, as well as a direct kidnappings and illegal policing actions with the support of usually authoritarian host governments.

Safeguard Defenders is currently tracking a number of other cases in the region (11 in Laos, four in Vietnam, nine in Thailand, and four in Myanmar), including for example Wang Bingzhang, Li Xin, Peng Ming, Gui Minhai, Jiang Yefei, and Dong Guangping.