China’s missing verdicts

This is the first in a series of small investigations and larger reports that look at changes in China’s criminal justice system and human rights since COVID-19. This article is best read as a PDF, click here to download it. The graphics may not be suitable for reading on mobile devices.

Following Safeguard Defenders’ investigation China’s criminal justice system in the age of Covid, comparing data 2018/2019 (pre-pandemic) with 2020/2021 (pandemic), released on 8 June 2022, this brief investigation, China’s missing verdicts - The demise of CJO and China’s judicial transparency, outlines the unfortunate deterioration of China’s earlier attempts at greater judicial transparency.

In 2013, China announced the establishment of a nationwide database to host not only criminal verdicts but also other court decisions. In 2016, this was followed by the establishment of a platform for videos of court and trial proceedings in 2016 (CTO, or China Trials Online). Together with an institutionalized mechanism for seeking public input into the drafting of key laws and revisions to existing laws, these moves were rightfully identified as positive developments for China’s opaque legal system.

In 2013, China announced the establishment of a nationwide database to host not only criminal verdicts but also other court decisions. In 2016, this was followed by the establishment of a platform for videos of court and trial proceedings in 2016 (CTO, or China Trials Online). Together with an institutionalized mechanism for seeking public input into the drafting of key laws and revisions to existing laws, these moves were rightfully identified as positive developments for China’s opaque legal system.

The database, China Judgments Online (CJO) or wenshu, has been instrumental for both domestic and international analysts to look at the execution of China’s criminal justice system on a macro-level, and played a key role in allowing Safeguard Defenders to produce a number of significant reports, among which for example exposés on the expanding use of secret detentions via the RSDL (‘residential surveillance at a designated location’) system, but also for two major upcoming releases on Exit Bans and the use of house arrests.

Unfortunately, these positive developments have come to a screeching halt, with significant consequences for our ability to identify and understand trends in Chinese law enforcement. It also coincides with a number of related and equally negative developments. This article sets out to do four things, namely:

- Briefly outline the rise of CJO

- The negative developments contributing to its demise as a research tool

- What kind of verdicts are going missing

- How the CJO can still be used to extrapolate data for a macro-level analysis of trends

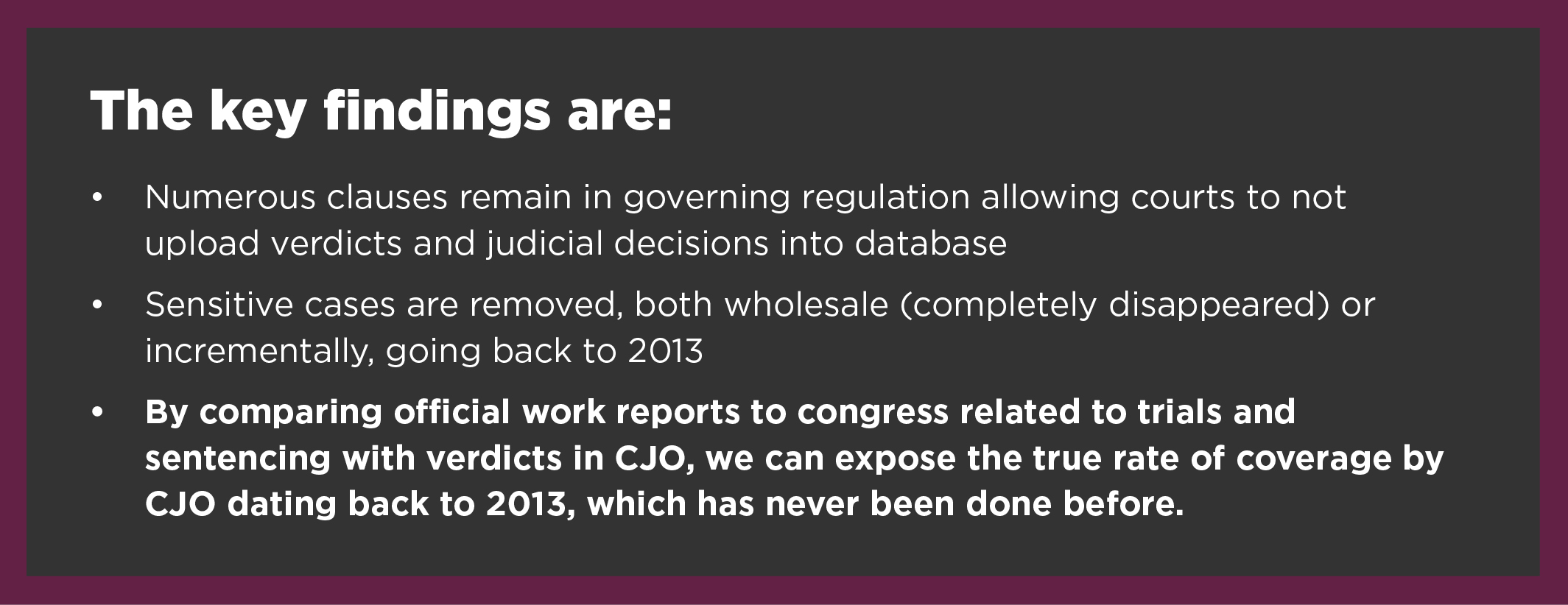

This brief article presents some key findings on how to use CJO, and how to extrapolate the data that does exist into something closer to the truth. The problem, from the very beginning, has been that a very significant amount of verdicts are never uploaded. It leaves gaping holes, as the difference between the amounts of verdicts concerning any given issue that is actually logged in CJO represents only part of the actual number of such verdicts. Safeguard Defenders can now present additional data, using official sources, to better understand the difference between the two, which will be of use for all future research drawing on CJO data.

The rise and fall of CJO

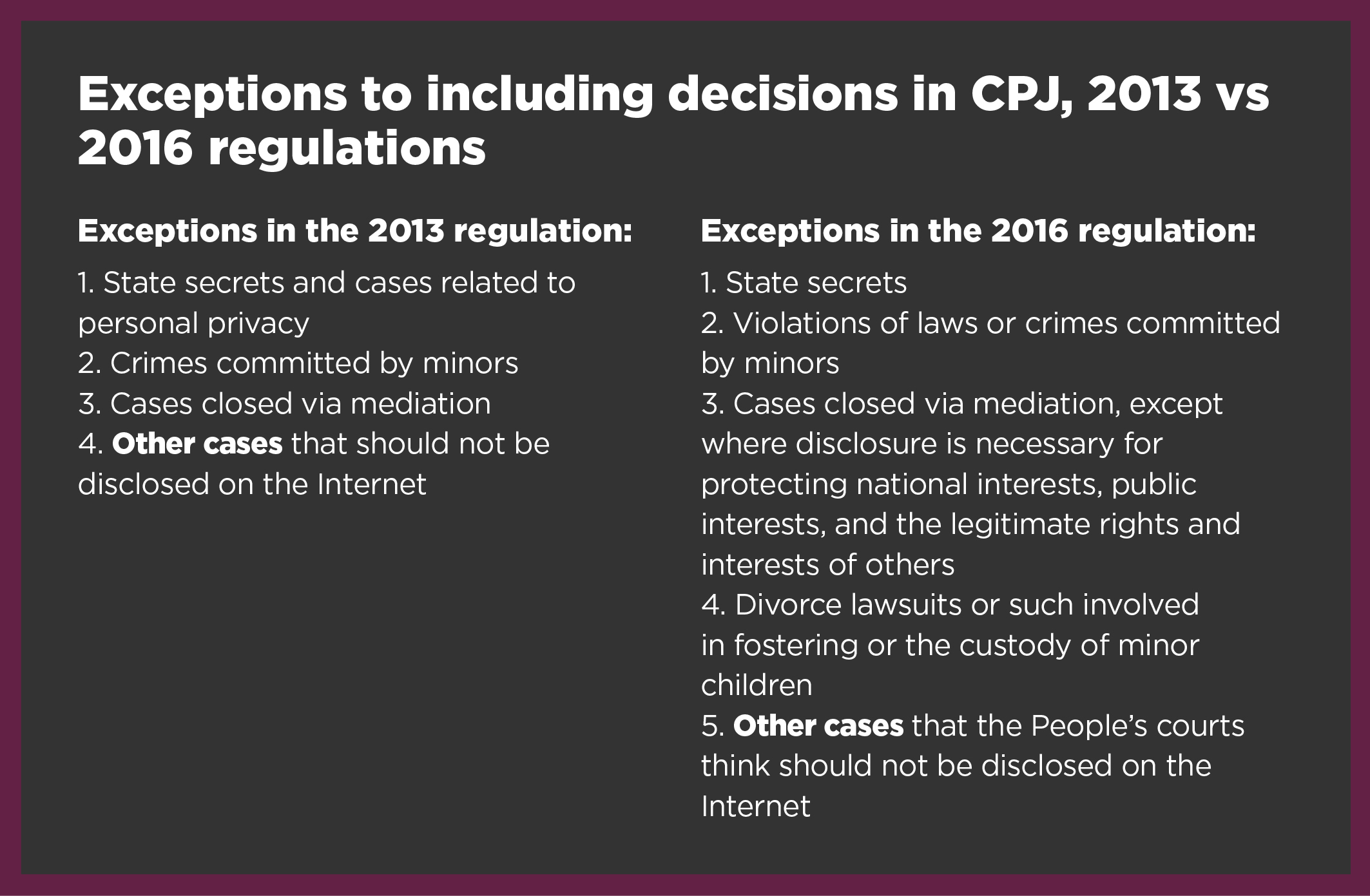

Upon the launch of the then much-heralded database, the Supreme Court (SPC) issued a regulation stating that all courts were to upload their verdicts within a week of their issuance, with some exceptions. This was followed by another regulation in 2016 which was supposed to limit the ability of judges to find ways to avoid uploading verdicts, an endemic problem from the very beginning. However, it also formalized more reasons why verdicts need not, or should not, be uploaded, thereby effectively institutionalizing exclusion of decisions and verdicts, with a catch-all category without any set definition.

There was resistance from the courts and judges from the very start. The SPC might have said that open access to judicial decisions would increase accountability and raise trust in the system, but it might easily have been seen by judges as a way to force their hands in how they carried out their sentencing and judgments, especially as the judicial corps in China continues to be woefully under-educated in the area of law. It was also thought of as a way to limit local authorities’ ability to influence court operations and outcomes, which, not surprisingly, would face resistance. If all judgments were made public, it would certainly be harder for local and regional courts to stray from the intended policy in Beijing, which could be seen as another attempt at centralizing power and control.

Nonetheless, the system was a marked improvement. One Beijing-based lawyer said to SCMP in an interview that “getting access to judicial decisions had been virtually impossible in the past but the situation had improved since the database, the world’s largest collection of judicial decisions, came online”. The then-President of the SPC said when it was launched that it would allow “…the public [to] see the judges’ efforts and better understand the ruling. The judicial process will no longer be a ‘black box’ and judicial credibility will be significantly improved.” The system, in its early years, received considerable praise from law scholars internationally and domestically, as well as by local legal practitioners. Yet, seemingly, it was not to last.

In a ChinaFile article published February 2022, Luo Jiajun and Thomas Kellogg said that during interviews with people within the judicial system, one judge at the Supreme Court itself stated there was concern some people might use the information as blueprints for copycat crimes, a rather ludicrous charge as verdicts rarely contain such detailed information that would allow replication based on those verdicts alone. Rather, as has been observed by Safeguard Defenders and various analysts, the verdicts most likely to disappear are those that may be considered sensitive in any respect.

“Judicial transparency in China has taken a significant step backward in recent months” Luo and Kellogg write in their article. They took note, like several other independent scholars and analysts, that going back to early 2021, perhaps even late 2020, verdicts and other judicial decisions on CJO were disappearing.

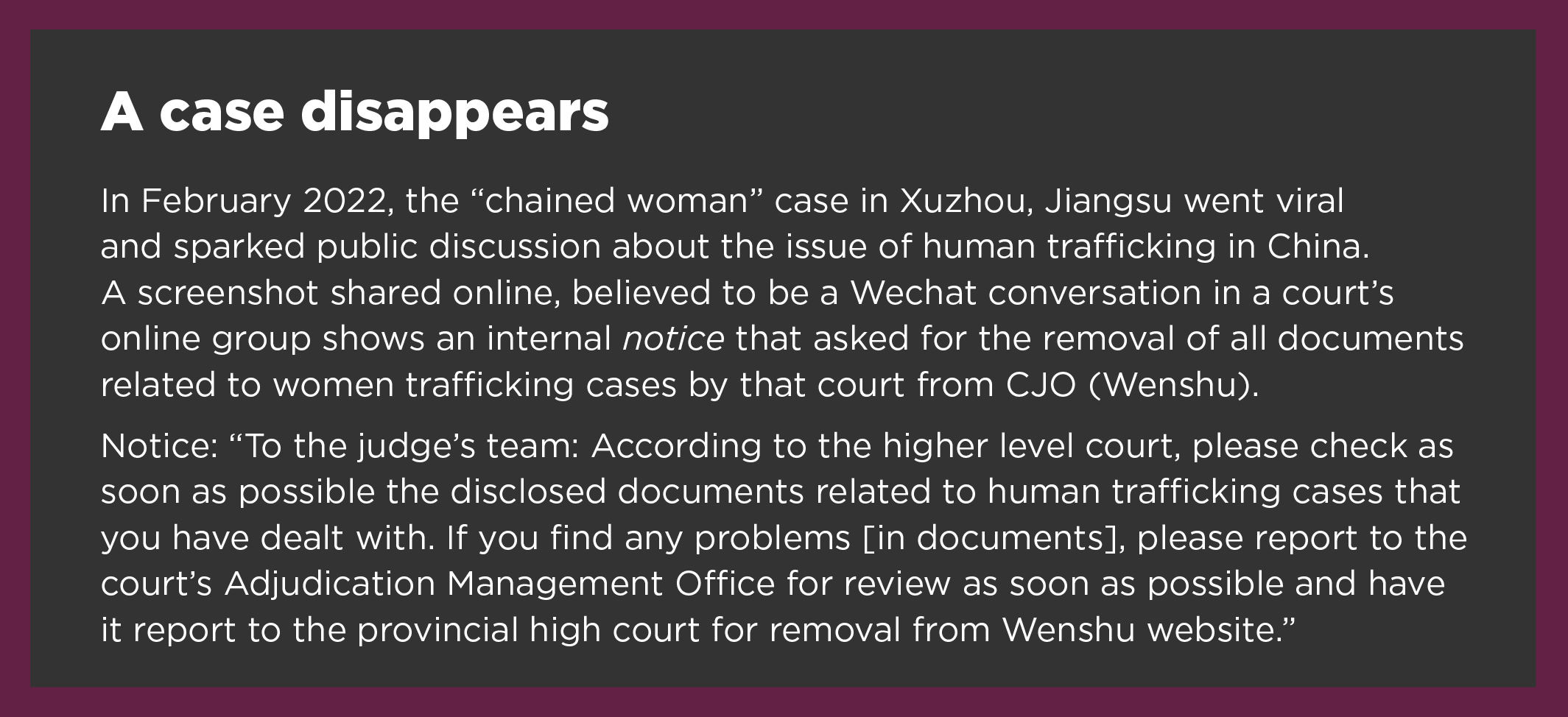

Around this time, Twitter user @SpeechFreedomCN, started collecting verdicts from trials related to social media use and “freedom of expression”, because he noted that they were rapidly disappearing. During this period, he identified and downloaded some 2,300 cases related to these keywords, available in aggregate form here (in Chinese), all of which have since disappeared.

Safeguard Defenders itself, which performs searches regularly on RSDL, started noting changes in the numbers, and not just for recent years, but going back all the way to 2013, and how the number of verdicts for each year started decreasing.

Then, in mid-2021, the Supreme Court announced it was ‘migrating’ court rulings in the database, and in one fell swoop 11 million judgments (of all kinds, not just criminal trial verdicts) were taken offline (although some may have reappeared later).

Safeguard Defenders’ study of RSDL illustrates how verdicts are disappearing. Our studies on the number of verdicts that have gone missing between 2013 and 2018, based on comparison searches carried out February 2020 and May 2022, showed that 736 verdicts, out of a total of 14,532, had gone missing for the period of 2013 to 2018, ranging, annually, from a high of nearly 17% of verdicts gone (2013), to a low of about 2% (2016), with an average for the entire period of 5.06%. It should be noted that since the RSDL issues received far more scrutiny from 2016 onwards, the number of cases in CJO was likely very low to start with. An earlier study, by CCP-aligned Jiangxi University researcher Xie Xiaojian, on RSDL cases in 2013 and 2014, showed 569 RSDL cases logged for 2013. Today that number is 270: 52.55% of verdicts related to RSDL for 2013 have since disappeared, step by step.

To give another example: the catch-all crime “picking quarrels and provoking troubles” (article 293 of the Criminal Law) has, when Safeguard Defenders conducted its latest search on 8 May (2022) zero entries. A search performed in May 2020 by Luo and Kellogg showed verdicts in the tens of thousands.

Searching for verdicts (criminal trials, first instance) that contain the words for Twitter, Facebook or Weibo yields merely 95, 170 and 2,179 results respectively, ever since 2013 (combining both Chinese- and English language search terms). Other verdicts being culled and disappeared are those referring to other sensitive issues and phrases, such as “freedom of speech,” “rumour,” “feminism,” and “national leaders”. There are, as of today, only three cases that refers to “freedom of speech”, and a total of 312 verdicts that have any mention of the Ministry of State Security (MSS).

Corruption and abuse of power cases have not been spared and as one would expect anecdotal searches and analysis confirm that verdicts that reflect badly on the Party or State are included in this purge. Often, media attention to a case can lead to a verdict’s abrupt removal. Luo and Kellogg identify an example:

“On June 8 [2021], a vice president and two fellow judges in the intermediate court in Jinan, the capital of Shandong province, were convicted of bribery after taking millions of renminbi from over 60 lawyers from different law firms over several years. The case highlighted systemic judicial corruption that included a number of key players, including judges, lawyers, large corporations, and state-owned enterprises. Lawyers caught up in the scandal included top members of the provincial-level lawyers’ association and well-known legal academics, which suggested that bribery had permeated both the court system and the legal profession up to the very highest levels in the province. After the scandal attracted national media attention, the verdicts in the case were removed from the CJO database, and further media reporting on the case abruptly ceased, most likely on orders from the propaganda authorities.”

To make things worse, there has been several studies on the regional disparities on how many cases are logged. One study (Ma Chao, Yu Xiaohong, He Haibo: Big data analysis: Report on the publication of Chinese judicial decisions on the Internet), China law review, 12(4), 2016: 208) found that by 2015, about 50% of decisions were being published, but it ranged from a high of 78% in Shaanxi, to a low of 15% in Tibet, with extensive variations in-between those extremes, with places like Beijing also scoring very poorly.

Beyond the culling and disappearance of a great number of verdicts, and other judicial decisions, there has also been a tightening of who can access the database, and how results can be collected. Users now need register with a local phone number (which since 2013 need be registered in your name and with ID card/passport information provided). With this, any searches performed can be traced to the individual user. Repeat searches and extended use often leads to time outs. And even though the total search result number still appear, only the initial results are viewable, and only those viewable allows the user to access the individual case, a severe constraint for any extended data collection.

At the same time lawyers noticed that China Trials Online, which publishes videos from trials, had also seen the disappearance of previously available videos of court proceedings.

The key problem is not actually the removal of ‘historical’ data, although it is a significant blow to macro-level analysis, but rather, if old cases related to topics now deemed sensitive are removed, then what does it mean for current cases? The answer of course is that restrictions on uploading new cases are likely even harsher than the removal of old ones. Hence, at whatever level old cases about a certain issue are being removed, it will likely have an even greater impact on the level of new cases related to the same topic being uploaded. It is, as far as studying Chinese law enforcement is concerned, the intentional application of fog of war. But all hope is not lost.

How to extrapolate data from CJO and counter the fog of war

A key issue in using the CJO for macro-level analysis - as done by Safeguard Defenders to expose the scale and scope of the use of the RSDL system - is to have an understanding how complete, or incomplete, the CJO is. Much research released by SD clearly separates between ‘officially logged’ number of cases, sentences or verdicts on a particular subject – the amount actually recorded in CJO, and an estimate on the true number.

Bridging this gap by being able to extrapolate realistic estimates based on ‘officially logged’ cases or verdicts is and will become even more important. It will also become harder as the amount of cases in CJO decreases, and as there seems to be top-down instructions to completely erase a certain type of verdicts, which in all likelihood also means to stop uploading new ones.

This in itself is nothing new, as cases related to ‘national security’, cases concerning or handled by the Ministry of State Security (MSS), cases related to ‘state secrets’ etc., have always or most often been excluded. What we are seeing now is that much broader categories, such as the crime of picking quarrels and provoking troubles, but also in general verdicts referencing feminism, rumours, or freedom of speech are disappearing, which could cut across a whole range of crimes.

Lawyers across China have for years operated under the assumption that only roughly 50% of verdicts that should be uploaded are actually uploaded (not counting the categories mentioned above that should never be included). A study by CCP-aligned Jiangxi University researcher (and former State Prosecutor) Xie Xiaojian analysed 1,694 verdicts related to RSDL between 2013 and 2014, and found that only 37.02% where found on CJO, and concluded that for some types of crimes, including corruption or cases concerning government officials, the number was even lower.

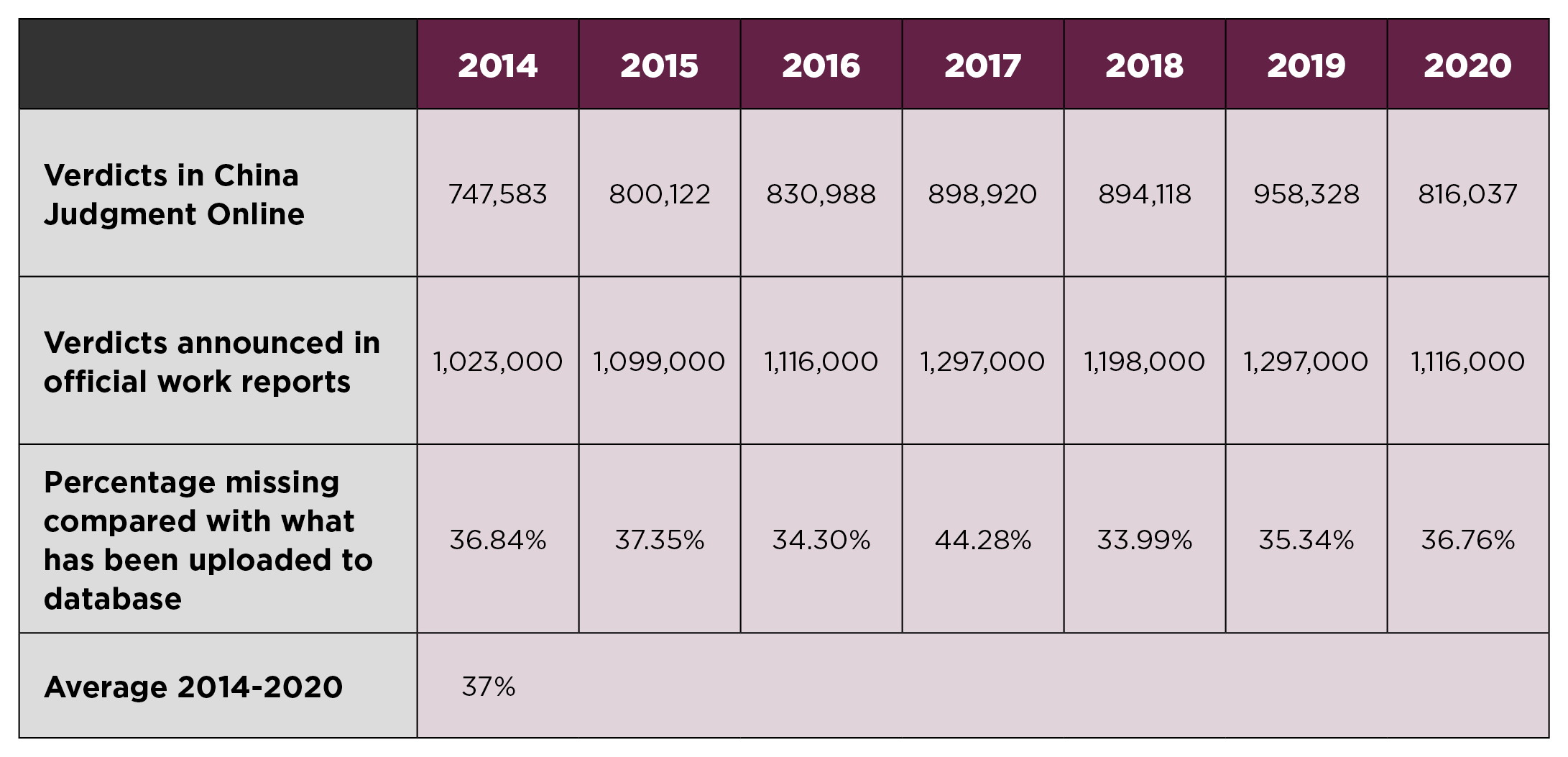

However, for issues, keywords or crimes that are not yet on the ‘kill list’ or otherwise deemed overly sensitive, there is a way to establish a rough idea of the amount of cases on CJO, which can then be used to extrapolate true estimates for non-sensitive issues. Safeguard Defenders has analysed the official Supreme Procuratorate and Supreme Court work reports submitted to the National People’s Congress in March each following year, and collected data on the number of judgments (criminal trials, first instance) for the years 2014 to (and including) 2020. It has then compared those numbers with the total number of verdicts found on CJO for those corresponding years, using the same specifics (verdicts, criminal trials, court of first instance).

The data shows that on average, for the years 2014 to 2020, some 37% of verdicts are missing from the database, varying between a low of 34% and a high of 44% for these years. As verdicts are often slow to be uploaded, using the last full year (2021) for comparison is not useful, and is not presented in the data below.

The average for the time period is thus that 37% of verdicts for criminal trials at court of first instance are missing. For more sensitive issues, or any issue under heightened scrutiny, that number is certainly much higher, and for some areas deemed off-limits now at 100%.

This to some extent corresponds to a paper by Tsinghua University professor He Haibo, who has long studied the CJO, and whose research showed that after the 2016 regulation came into effect, the amount of cases being uploaded did increase, and in 2017 reached about 60% or about 14 out of 23 million judicial decisions in total (not just criminal trial verdicts).

In addition, this is only the amount of cases missing based on what is reported to the NPC, and it is possible national security trials, state secrets trials, etc., are not included in their reporting, meaning this percentage of missing verdicts is a minimum.

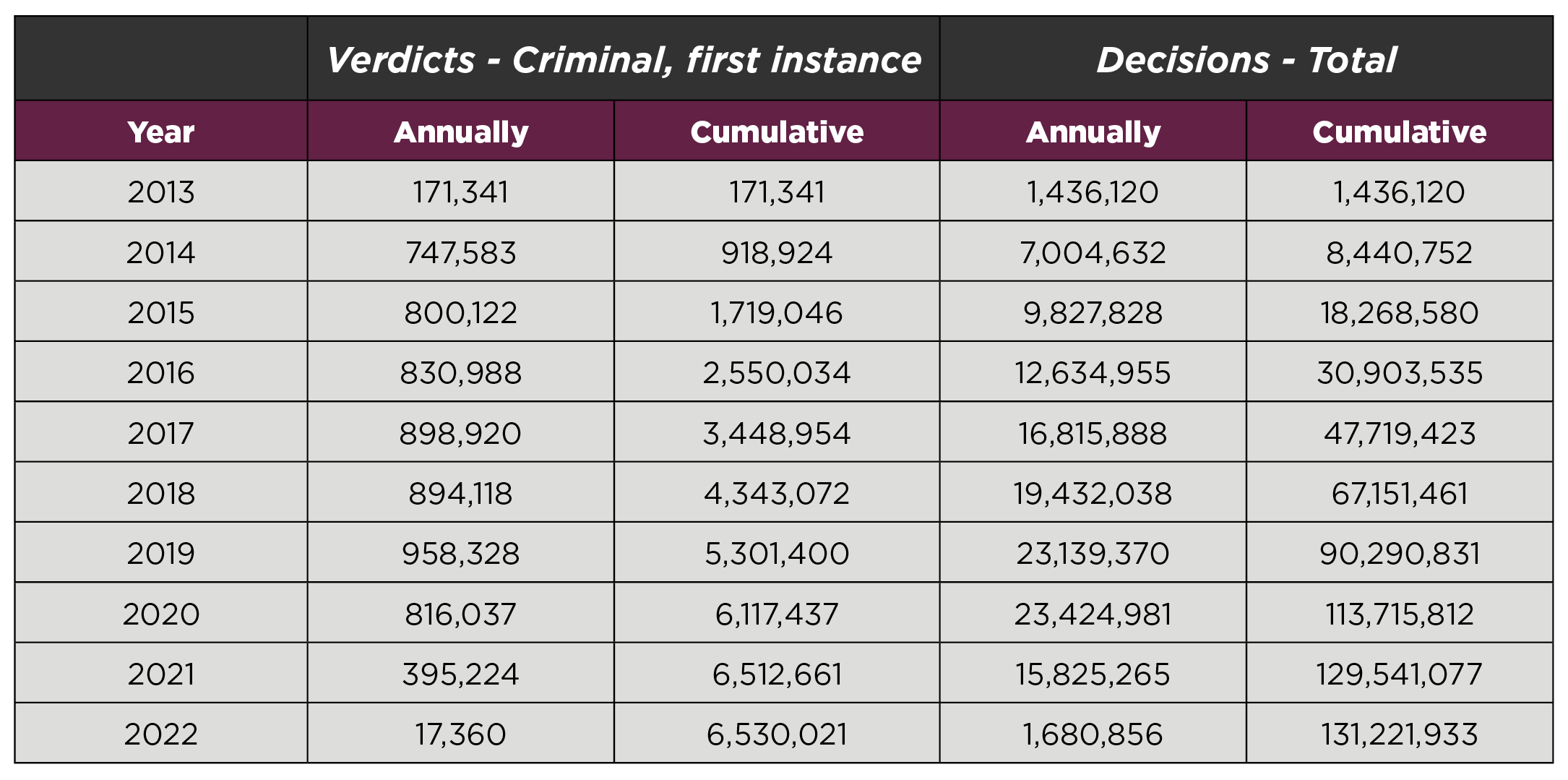

There are, as of 8 May 2022, 6,530,021 verdicts for criminal trials for court of first instances in CJO (dating back to 2013), while the total number of judicial decisions number 131,221,933.

Data breakdown, by year, for both verdicts in criminal trials (first instance) versus total number of judicial decisions, is as follows (as of 8 May 2022), with cumulative value at end of each year.

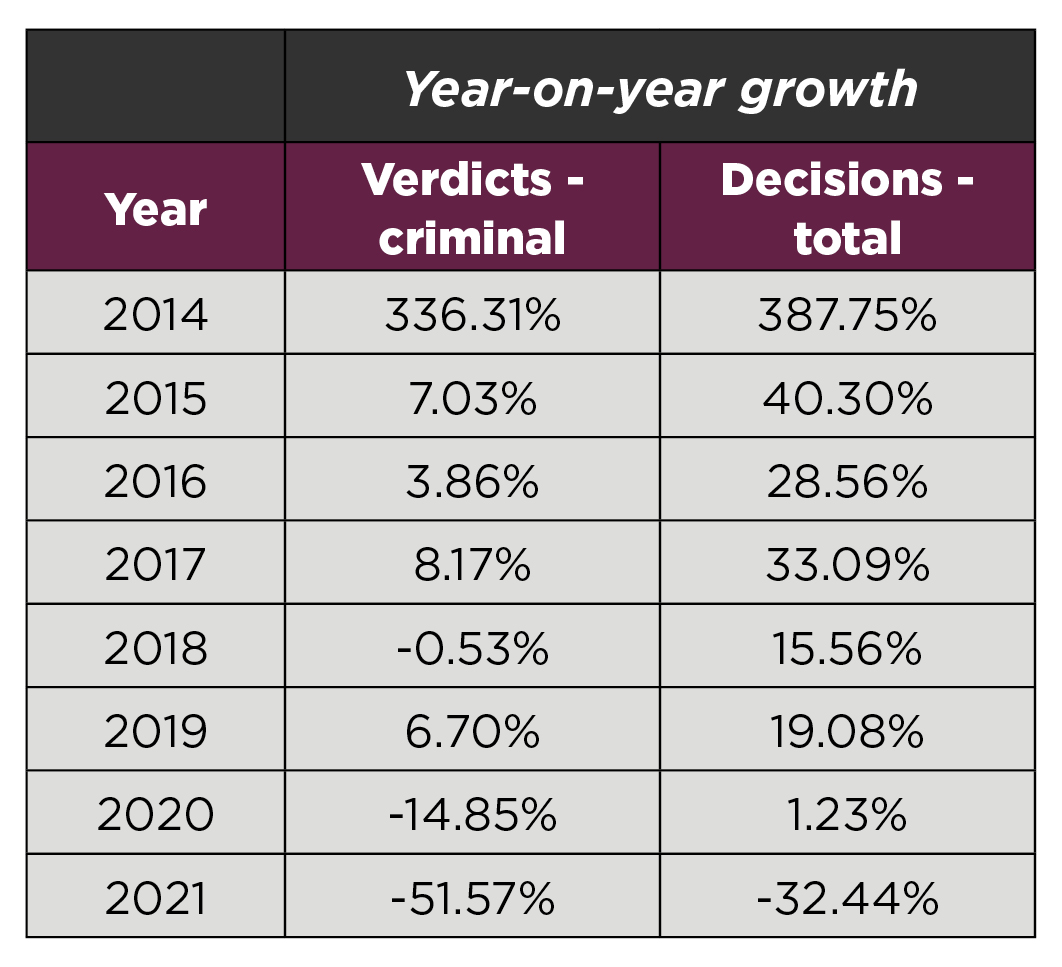

The year-on-year growth, for 2014 to 2021, for both verdicts at criminal trials at first instances vs judicial decisions in total, provides the following data. This data does show that in 2017, following the new 2016 regulation, there was an unusual increase in verdicts being uploaded, as analysed by He Haibo at Tsinghua University, but it was a short-lived boom. And even though data for 2021, and perhaps to some extent 2020, is simply too new to be fully usable, the dramatic decline in uploading verdicts, which is far greater than the more modest decline for all judicial decisions, may indicate which way things are going.

For further comparison with the number of actual prosecutions, trials and sentences delivered, year by year, which has grown continuously for all years (with exception of 2020, the first year of the pandemic) see SD’s investigation China’s criminal justice system in the age of Covid, which makes clear that these variations in uploading of verdicts to CJO has little do to with the growth in trials and sentences.

As the data herein can be of great use in macro-level analysis of China’s criminal justice system, and helps SD uncover the scale and scope of numerous human rights violations which otherwise cannot be analysed in terms of quantity, it is our belief that understanding how CJO works, and how much is missing from it, can and will be an important tool.