Analysis - Swedish parliament’s report on mismanagement of Gui Minhai and Dawit Isaak case

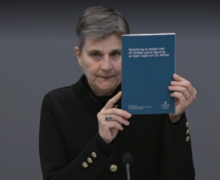

Review of the Granskning av arbetet med att försöka uppnå frigivning av Dawit Isaak och Gui Minhai SOU 2022:55 (Review of the work to try to achieve the release of Dawit Isaak and Gui Minhai[i])

Review of the Granskning av arbetet med att försöka uppnå frigivning av Dawit Isaak och Gui Minhai SOU 2022:55 (Review of the work to try to achieve the release of Dawit Isaak and Gui Minhai[i])

Released October 28, 2022, 158 pages

Link to the press conference (October 28), click here. The report, with English summary, can be downloaded as PDF here.

Guest post by Susanne Berger and Magnus Fiskesjö, November 1, 2022

Over the course of the last 30 years we have dealt with various official Swedish investigations into highly sensitive subjects, including several long-term missing person cases. In the process, We have reviewed and analyzed many so-called SOU (Statens Offentliga Utredingar) - Official Governmental Investigation reports.

Unfortunately, we have to conclude that the eagerly awaited review of the official Swedish handling of the lengthy, illegal imprisonment of two Swedish citizens abroad – Swedish-Eritrean playwright and author Dawit Isaak, who has been held in Eritrea without charge or trial since 2001; and the Swedish publisher Gui Minhai who was kidnapped from Thailand by Chinese Security forces in 2015 and subsequently incarcerated in China on trumped up charges – falls short of the mark.

This minimalistic volume, the result of a more than twelve months long investigation, does little credit to the commission that authored it; nor – more importantly - does it do justice to the two Swedish citizens and their families who are desperately waiting for a signal that the Swedish government is pursuing their cases with a proper sense of urgency and a willingness to maximize all reasonable options at its disposal. Instead, the message conveyed in the commission’s report sounds strangely anemic, perfectly reflected in the lifeless, somber grey tones that permeated the early Friday morning presentation of the group’s findings at an official press conference.

Photo: Gui Minhai's kidnappers entering his condo compound, Pattaya, Thailand.

While the chairperson of the commission Helena Jäderblom, a respected jurist and former judge at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), did her level best to infuse some life into proceedings, the impression left by her presentation was strangely uninspiring. Not even Jäderblom’s obvious dismay at the fact that – contrary to the Swedish government’s earlier assurances – the commission was not permitted to review all documentation in the Dawit Isaak case, due to unspecified secrecy restrictions, could light a spark with the dozen or so members of the Swedish media in attendance. In essence it means that the government prevented the commission from carrying out important aspects of its assigned task. This point alone should have engendered a lively discussion.

Our initial search of the text for the term “silent diplomacy” (tyst diplomati) yielded no hits. A closer inspection confirmed that this “investigation” was a more or less a summary of official Swedish steps taken through the years, with no serious analysis of their efficacy or detailed recommendations how to resolve the current stalemate. It was left to newly appointed Foreign Minister Tobias Billstrőm to sum up what everybody knows but few dare to publicly acknowledge – that the fact that the Swedish government has not succeeded in procuring the release of either Dawit Isaak or Gui Minhai or even managed to obtain any reliable information about their physical condition or whereabouts has to be viewed as a fundamental failure – even taking into account the extremely difficult challenges involved when dealing with not one but two totalitarian regimes.

On the positive side, it was heartening to learn that, according to the commission’s assessment, official Swedish efforts have not flagged through the years, and that Swedish officials have pursued both cases with “intensity and great engagement.” However, the commission report provides no meaningful details on the ultimate effects of these intense efforts – no comment on the strategic failure to cling to a policy of silent diplomacy that, in the case of Dawit Isaak, has not yielded any tangible results in over 20 years; or a proper evaluation of the Swedish government’s more recent decision to seek a constructive “engagement” with Eritrea while obtaining not even minimal concessions from the Eritrean regime in return; nor a detailed examination of the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s role in the Swedish Prosecutor’s Office repeated refusal to open a criminal investigation of the Eritrean leadership for crimes against humanity. Not to mention the fact that since 2018 Sweden has had no response from the Chinese government to its requests for a proof of life for Gui Minhai or any formal documentation regarding his trial and conviction in 2020 for alleged “illegal intelligence activities” which saw him sentenced to a ten-year prison term.

Instead, in a euphemistic understatement, the commission concluded that in spite of all the good faith efforts, there were “certain shortcomings” in the official Swedish management of the two cases. These include a failure to create a comprehensive compilation of relevant background facts, no proper analysis and evaluation of applicable domestic and international legal remedies (which instead have been pursued over many years, for example, in the case of Dawit Isaak by his Swedish legal team, with more recent support from an international coalition of human rights organizations, led by the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights in Montreal, Canada); and - last but not least - a serious failure in the Foreign Ministry’s internal and external communications.

To outside observers all this may sound a bit disconcerting, but not too bad overall. Well, this is what these "certain shortcomings" mean in reality: Dawit Isaak’s arrest in 2001 barely registered in the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s consular apparatus (which is tasked with assisting Swedish citizens abroad) – despite the fact that he was a Swedish citizen since 1992. It took months before Swedish diplomats felt it necessary to conduct certain inquiries on his behalf. When he was released from prison in 2005 – in what we now learn was merely a provisional release – careless self-congratulatory comments by Swedish officials in the international media led to Dawit’s almost immediate re-incarceration. He has never been heard from since.

Photo: Gui Minhai's condo apartment in Thailand after he had been kidnapped.

Similarly, instead of providing Gui Minhai with proper diplomatic protections, the decision to transfer him to Beijing for a medical examination by train after his initial release from a Chinese prison in 2017 instead of choosing a more secure means of transportation, i.e., by diplomatic car, turned out to be catastrophic. The equally disastrous decision by the former Swedish Ambassador to Bejing Anna Lindstedt to take up the offer of two unvetted Chinese representatives to provide Gui Minhai’s daughter Angela Gui with a job offer in return for her toning down the public advocacy on behalf of her missing father receives is but a passing mention. It still remains unclear what knowledge some members of the Swedish Foreign Ministry had of the scheme. The biggest revelation appears to be that in 2017, the former Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lőfven raised Gui Minhai’s imprisonment directly with Chinese Premier Xi Jinping, without mentioning Gui by name. However, the report stays mum on the question if Lőfven should have traveled to China in the first place without obtaining prior assurance of Gui Minhai’s release.

The commission clearly does not wish to enter into any such detailed examination. Instead, it appears content to skip along the surface, not creating too many waves. As Helena Jäderblom stated in her presentation, the commission members remain beholden to certain secrecy restrictions, but this alone cannot account for the overall vagueness and lack of depth of its findings. Surely both the Dawit Isaak and Gui Minhai cases involved interactions with Swedish and foreign intelligence representatives – no mention of any such contacts in the report. Source references of communications with foreign entities are noticeably absent. We also learn almost nothing about perhaps the most important avenue of all, the EU, of which both Gui Minhai and Dawit Isaak emain citizens. There have been hints in the press about the astonishment of EU countries noticing Sweden's passivity, yet Swedish authorities have claimed that they consistently utilize the EU route. The report’s recommendation section is as brief and incomplete as the foregoing text: Improve internal and external communications; get all your facts together (reports by Safeguard Defenders and Reporters without Borders show how it’s done); brush up on your legal options (which constitutes an acknowledgment, albeit implicitly, that all is not well with the government’s handling of the two cases). One cannot help but wonder what the failure to check off even these most fundamental boxes means for the seriousness of the Swedish Foreign Ministry’s campaign. The commission also has nothing to say on what role public advocacy can or should play in future official efforts to secure Dawit Isaak’s and Gui Minhai’s release.

Any hopes that the Swedish authorities could use the commission’s review as a decisive marker, a fresh impetus for seeking a broader, and possibly more effective approach, look dim. But then, the hopes for such an outcome were never that high to begin with. While providing a helpful summary and very useful outline of various legal and administrative aspects concerning the two cases, this commission did not manage to do what is needed most: To seize the moment and provide a comprehensive, unvarnished assessment of the government’s actions to date and pointing a more specific way forward to a possible resolution of Gui Minhai’s and Dawit Isaak’s tragic ordeal. As such, the report is of limited utility. This is especially regrettable since the commission interviewed numerous frontline activists with first-hand experience who, in great detail, outlined what mistakes had been made, what the missed opportunities had been, and where incompetence had led to numerous delays which put any effort to assist Gui Minhai in jeopardy. It also outlined failures in diplomatic communication bilaterally and multilaterally that the government could have employed to assist Gui, and how to better proceed, including specific types of leverage that could be employed to, if not free, then at least guarantee better treatment of Gui. None of this appears in the report, ensuring that the report, in its current form, stands no chance of helping improve future government assistance to political prisoners like Gui Minhai and Dawit Isaak.

- Susanne Berger is a Senior Fellow with the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights (RWCHR)

- Magnus Fiskesjö teaches anthropology and Asian studies at Cornell University, USA. Previously he was director of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm, Sweden, and in the 1980s, he was cultural attaché at the Swedish embassy in Beijing, which is when he first met the young poet and writer Gui Minhai.

End note from Safeguard Defenders: For more details on how the Swedish government missed opportunities, failed to seek input and information, and delayed actions, sometimes for months, see the end part of Safeguard Defenders mapping of how Gui Minhai was kidnapped in Thailand.

[i] See also Granskningskommissionen avseende två konsulära ärenden (UD 2021:01) [Investigative Commission concerning two consular issues]