Extradition in Morocco, Interpol and secretive agreement with Turkey

On October 27th, Yidiresi Aishan (also known as Idris Hasan) will reappear before Morocco’s Court of Cassation in Rabat over a pending extradition request from the People’s Republic of China. In a case that has gathered worldwide attention, this will be the fifth session before the Court since Aishan was arrested on the basis of a (flawed and later canceled) Interpol Red Notice upon arrival at Casablanca airport on the night of July 19.

Three months into his detention and ahead of his latest Court date, time for a quick recap and some impelling questions over the international policing cooperation framework crucial to Beijing’s increasing long-arm repression and persecution.

Key points

- Updated status of judicial proceedings before Morocco’s Court of Cassation

- UN Special Procedures appeal to Moroccan authorities to stop the extradition

- Turkey’s secret Joint Security Cooperation Mechanism with China and communications confirming China’s pressure over Uyghur residents in the country, and of direct pressure from local police in Xinjiang

- Interpol fails to provide his defense with the “new information” that led to the cancellation of the Red Notice

- Interpol’s review was based only on international media reporting and failed to vet the request despite the extensive reporting on abuses in Xinjiang and against Uyghurs

- Interpol General Assembly at end of November an opportunity to adopt a resolution regarding “cases concerning serious international crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes)” in the PRC under Article 3 of Interpol’s Constitution.

Background

After graduating in Xinjiang, Aishan moved to Turkey in 2012 where he worked as a computer engineer and lived with his wife and three children. Members of the Uyghur community state he was frequently active in assisting other members from the exile community in translation efforts with local authorities. At least from 2016 onwards he becomes active in an Uyghur diaspora newspaper in Turkey, assisting other activists in media outreach and collecting testimonies on the atrocities in Xinjiang, and has been a public speaker at Uyghur diaspora events.

Between 2016 and 2018, he was detained three times by Turkish authorities and held for a span of several months. A Turkish tribunal document from 17 March 2017, ordering his immediate release from the Kayseri Removal Center, documents his first detention starting 29 October 2016 with the express scope of deportation. Following two more stints in the center, Aishan is issued a Turkish residence permit on 2 April 2020, and a criminal record issued by Turkish authorities in March 2021 holds no citations.

Aishan had expressed repeated fear of being deported, both due to direct requests made by local county police in Bugur County, Xinjiang, and a document marked “secret” from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Turkish Ministry of Justice (with copy to the Head of the Turkish National Intelligence Agency) on 26 March 2020, citing:

Likewise, in the aforementioned Ambassador's Note attached, it is requested to share the details of the judicial process carried out regarding the individuals named Idris Hasan, Anver Turde, Abdulhever Celil, Nesrullah Maimaiti, Abuduriyimu Maimaitiali, Ali Ablat and Mehmet Yusuf Adbulhkerem.”

At the time of writing, SD has not been able to obtain any further details on the scope or date of entry into force of the cited Joint Security Cooperation Mechanism between Turkey and the PRC.

The above naturally spooked Aishan. Feeling increasingly unsafe, he attempted to leave Turkey three times prior to boarding his fateful July 19th flight to Casablanca. His relatives relay how while he was not rebuked from leaving this time, Istanbul airport border control questioned him for half an hour and reportedly warned him that “if he left, he would not be able to return”. At no point was he informed that an Interpol Red Notice had been issued in his name. Upon his arrival at Casablanca Airport he was immediately detained and transferred to Tiflet Detention Centre from where he called his wife on July 24th stating he had been informed that he was to be deported to the People’s Republic of China.

At the very time he was being arrested in Morocco and after three years without any contact whatsoever, his family suddenly received a call from Aishan’s father-in-law in Xinjiang, asking where he was. Together with the direct approaches made prior by local county police, these are trademark practices of Chinese authorities, indicating the clear intent to have the person returned by any means necessary.

SD was contacted by members of the Uyghur activist diaspora and informed of the case on July 25th and asked to provide Aishan with legal counsel, a process formally initiated on July 27. In the meantime however, Morocco’s General Prosecutor met with an unassisted Aishan on July 26th, issuing an immediate recommendation to proceed with the requested extradition to the Court of Cassation despite the objections and fears of torture made by Aishan and the fact that no official extradition request had been made by Chinese authorities at that time.

During his formal deposition on July 20th, Aishan stated: “I have been informed of the international arrest warrant regarding a terrorism affair, but I am not aware of its subject. This is my first visit to Morocco. I have been accused of this because of my Muslim religion and if I am extradited to China, I will be executed” (Translation from official document in Arabic).

Despite these objections, on July 27th the General Prosecutor recommended: “It is requested that the received documents are presented before the Criminal Chamber of the Cassation Court, while awaiting the official extradition documents, in order to issue a decision delivering a favorable opinion regarding the extradition the subject to the Chinese authorities” (translation from official document in Arabic).

Morocco – China Extradition Treaty

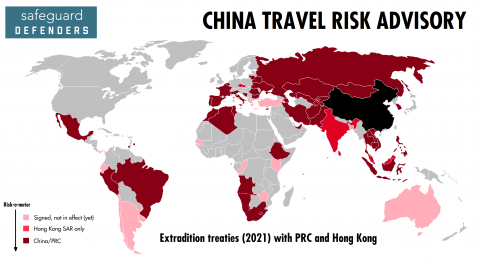

Aishan’s case is the very first since the entry into force of the Extradition Treaty between Morocco and the PRC, following China’s ratification only last January 22nd. The PRC’s recent heavy investment on the signing and ratification of such bilateral treaties has been highlighted by SD before and will be extensively examined in two comprehensive forthcoming reports on extradition and involuntary returns.

Morocco and China had signed the Treaty on May 11, 2016, in the framework of a strategic partnership between the two countries with no less than fifteen agreements signed on the same day by King Mohammed VI and Xi Jinping at the People's Palace in Beijing, relating in particular to the judicial, economic, financial, industrial, cultural, tourist, energy, infrastructure and consular fields. Morocco ratified the extradition treaty in 2017.

On the basis of this treaty, Moroccan authorities informed Chinese authorities of Aishan’s arrest on July 20th. A communication acknowledged by Beijing on August 13th:

“Reference is made to your message dated 20/07/2021 regarding our fugitive AISHAN Yidiresi. NCB Beijing extends its warm regards to NCB Rabat and extends our sincere greetings and thanks for your great efforts on this case. According to Article 6 of the Extradition Treaty between People’s Republic of China and the Kingdom of Morocco, you are kindly requested to provisionally arrest the fugitive AISHAN Yidiresi with a view to extradition and keep him in custody until the extradition is completed. We will submit the extradition request through diplomatic channel as soon as possible.”

The July 20th date is relevant as it started the clock on the 45-day time limit Chinese authorities had to transmit the formal and documented extradition request to Morocco per the terms of the bilateral extradition treaty. This request did not arrive until the very last moment as communicated during the Court’s third hearing in the case on September 1st, explaining why prior Court sessions of August 12th and 26th led to successive postponements.

The legal defense team was provided with a copy of the formal extradition request by the Cyber Security Department of the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MPS) dated 24 August 2021, on September 7th. The request cites charges for “forming, leading and participating in terrorist organizations, advocating terrorism or extremism or instigating terrorist activities”.

During the subsequent Court hearing of September 22nd, Aishan’s legal defense team raised questions over the legal standing of Aishan’s arrest given the suspension and subsequent withdrawal of the Red Notice by Interpol (see below) as well as the standing of the extradition request’s issuing authority MPS per provisions of the bilateral treaty. The requests were granted by the Court and session was postponed to October 27th.

In the meantime, four UN Special Procedures issued a letter to Moroccan authorities on August 11, published following the 60-day time limit, stating: “Although we do not wish to prejudge the accuracy of the allegations above, we express our deep concern about the potential extradition of Mr. Aishan to China, where he is at risk of torture and other mistreatment, both for belonging to an ethnic and religious minority and for his accusation of being affiliated with a terrorist organization. We wish to remind your Excellency's Government of the absolute and indiscriminate prohibition to return persons to a place where they are at risk of being subjected to torture or other ill-treatment. Article 3 of the Convention against Torture (CAT) provides that "no State Party shall expel, refouler or extradite a person to another State where there are serious grounds for believing that they might be subject to torture ”and that“ in order to determine whether there are such grounds, the competent authorities will take into account all relevant considerations, including, as in the present case, the existence in the State concerned of a series of systematic serious, flagrant or mass human rights violations.” (Translation from original in French).

Safeguard Defenders provided the defense team with an extensive brief into systematic and widespread practices of violations of international legal safeguards and standards in judicial proceedings in the PRC, enforced disappearances, torture, forced confessions as well as consistent violations of diplomatic assurances and consular agreements.

Interpol

While Aishan was arrested on the basis of a Red Notice issued in his name, Interpol quickly moved to first suspend (prior to the provisional arrest request from the PRC to Morocco on August 13) and then cancel the notice following the global media and political attention surrounding the case. However, while citing “newly received information”, Interpol has not provided any further insight into its content.

As it appears evident that any such “new information” - considered substantial enough to quickly suspend and withdraw the Red Notice – might be paramount to the defense in Morocco, especially given the fact that Morocco’s internal extradition process does not provide for an appeal procedure to the Court of Cassation’s decision, his advocates hoped Interpol would be more forthcoming.

Instead, a first request to the organization made on behalf of Aishan’s wife to obtain such “new information” on September 15th - prior to the September 22nd Court session - was returned to sender on October 7th with the statement that such a request can only be made on express power of attorney of the defendant himself, clearly underestimating the obvious difficulties faced in a transnational case and the severe time restraints on the defense team. A renewed request to the Commission for the Control of Interpol’s Files was made on October 8th by Mena Rights Group and Safeguard Defenders.

It is striking that in ignoring the urgency in the defense’s needs for a case where they clearly “dropped the ball” in performing the necessary checks prior to issuing the notice given its swift repeal as soon as the case came to public attention, Interpol seemingly continues to ignore its moral obligation to provide Aishan with all information at their disposal in a timely fashion. As time passes, the looming doubt is that Interpol may not in fact have acted on the basis of new substantial information, but rather felt the heat created by international media reporting. In either case, its direct and grave responsibilities in the persecution of this Uyghur man are evident.

Aishan’s case once more highlights the dangerous role played by international judicial and policing cooperation mechanisms when these include countries not abiding by the rule of law and international human rights standards. Urgent scrutiny and reform of these mechanisms is needed as authoritarian regimes such as the PRC seek to extend their long-arm policing efforts to crack down on dissent around the world.

Their unquestioned inclusion legitimizes its (extra-)judicial system despite repeated grave concerns over enforced disappearances, unfair trials, torture and forced confessions raised by multiple independent UN human rights mechanisms. Furthermore, its lack of transparency and adequate means for independent checking poses a serious and constant risk to fundamental rights such as freedom of speech and movement around the world, as exemplified by the warnings issued recently by intelligence services to Danish and British activists and lawmakers vocal in their condemnation of the Chinese Communist Party. The recommendation to avoid travel to countries with bilateral extradition treaties (of which ten are within the European Union alone) immediately impacts their rights and their ability to conduct their work freely.

While some recent extradition cases to the PRC within the European Union have all been rejected after lengthy judicial proceedings, the cost on the individuals struck by Red Notices of which they were unaware has been too high. In Poland, Swedish Falun Gong adherent Li Zhihui was detained for two years as the local court debated his extradition. During his time in prison, a man facing his same unfortunate fate, Yu Hao, did not resist to the stress of uncertainty and fear of being extradited to the PRC. Yu took his own life at the same Warsaw detention center after more than two years of waiting.

Interpol’s Constitution expressly states the organization must operate with respect for fundamental human rights (Article 2) and strictly forbids it to undertake “any intervention or activities of a political, military, religious or racial character” (Article 3). The fact that despite the right granted to each individual to request access to files potentially filed in their name, such access is not granted on a timely basis but may take up to four months and that the burden of contrasting potential filings lay on those listed, creates a clear tension with the obligation to safeguard fundamental human rights when authoritarian regimes accused of genocide and crimes against humanity are an integral part to it.

Not all blame can be put onto the poorly staffed organization itself though. With the upcoming Interpol General Assembly at the end of November, its democratic Member States have a possibility to act to counter the PRC’s abuse of the system in proposing and adopting a resolution in line with the repeated condemnation by Parliaments around the world and UN Special Procedures regarding the allegations of “cases concerning serious international crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes)” in the PRC, thus allowing the Commission for Control of Interpol’s Files to take these into account when reviewing PRC requests under Article 3 of its Constitution. Secondly, as repeatedly demanded by the European Parliament, EU Member States must suspend or end their bilateral extradition treaties with the PRC as a matter of urgency given they are in direct violation of fundamental freedoms guaranteed to all its citizens. Thirdly, countries all over the world need to review their judicial and policing cooperation mechanisms with the PRC to ensure they are in line with basic human rights protections and international legal standards.