Gui Minhai by his friends and family

Gui Minhai – the Swedish man now held in secret detention for the second time in China -- is usually referred to as a bookseller or a publisher. But Gui is also a father and a friend; a poet and a writer; and a scholar and a businessman. RSDLMonitor has tried to capture the man behind the headlines. The man who remains disappeared by the Chinese state, the man forced to appear in three forced televised confessions and the man who his daughter fears she will never see again. The photo above shows Gui Minhai giving his third forced confession to pro-Beijing media from a screenshot on the Oriental Daily's website.

Gui Minhai – the Swedish man now held in secret detention for the second time in China -- is usually referred to as a bookseller or a publisher. But Gui is also a father and a friend; a poet and a writer; and a scholar and a businessman. RSDLMonitor has tried to capture the man behind the headlines. The man who remains disappeared by the Chinese state, the man forced to appear in three forced televised confessions and the man who his daughter fears she will never see again. The photo above shows Gui Minhai giving his third forced confession to pro-Beijing media from a screenshot on the Oriental Daily's website.

Brief bio

Gui Minhai was an undergraduate student at China’s prestigious Beijing University when he first met poet Bei Ling in the mid-1980s and they bonded over poetry. After he graduated, Gui worked for a government publishing house in Beijing; his interest in Sweden was sparked when he met Magnus Fiskesjö who was working at the Swedish embassy in the Chinese capital. Gui moved to Sweden to study for a master’s and then PhD at Gothenburg University. He settled in Sweden, became a Swedish citizen, got married and had a daughter, Angela Gui . Years later, Gui opened a green tech company in China, and then later moved to Hong Kong where he became a board member of free speech NGO, the Independent Chinese PEN Centre (with Bei Ling), worked for a publishing house, and then opened his own publishing company where he worked with bookshop manager Lam Wing-kee, producing salacious titles on China’s political elite. He was kidnapped from his home in Thailand in October 2015. He has not been truly free since.

Gui Minhai, my father and my friend: Angela Gui, daughter

What was your relationship with your father like? “[It’s] always been very laid back and friendly. We’ve been able to talk about most things. He’s been able to talk to me about personal things and I’ve been able to talk to him about things in my life as well. So that’s something I’ve always appreciated very much about our relationship -- that he was more like a friend as I grew older than a father.” Why did your father want to leave China for Sweden in the 1980s? “I know that he wanted to study outside China – to see something different. …Many of his friends at the time were interested in the western influences that were being let in at that time so I suppose he wanted to see this kind of new world, in a way for himself… I think he was happy [in Sweden]. He always tells me about the blue skies and the crisp fresh air in Sweden compared with Beijing.” Was he worried about his safety before he was kidnapped by the Chinese state in 2015? “Even though we had quite a friendly relationship he was still my father, so he probably wanted to protect me in a sense and didn’t want me to worry. I understand he must have had threats before he was taken but this was never anything that he would mention to me. I did ask him a few times whether he thought that what he was doing was safe and were there any risks and he would say: ‘I’m a Swedish citizen. What I’m doing is completely legal in Hong Kong, so there’s no way in which anything I could be doing could land me in trouble.’ … I think he was a bit cautious, but I don’t think he ever anticipated anything as dramatic as that would happen. “I’m afraid we’re at a point where intervention might be too late. I really wish that the international community would have taken a bigger interest and made clearer public statements at the beginning because I think it’s at a point now where the Chinese government -- or whatever part of the Chinese government it is that is holding my Dad -- has had plenty of time to construct a case against him. I think that especially after this latest incident [Gui Minhai’s second kidnapping on the train to Beijing] I’m afraid … it might be too late now."

‘I’m a Swedish citizen. What I’m doing is completely legal in Hong Kong, so there’s no way in which anything I could be doing could land me in trouble.’

What are your strongest memories of your father? “[My Dad and I] used to watch drama and action films together. Because they were kind of ridiculous, we used to laugh at them and incorporate the very dramatic dialogue and turns of phrase from these films into our everyday language. It was kind of an inside joke. The last one we saw was The Planet of the Apes. There’s this bonobo male, he was evil and he overthrew the chimpanzee leader and he says something like 'Apes Follow Koba now' because his name is Koba and that’s something we used to say to each other. It’s one of the particularities of a relationship between two people… It’s something that I would like to have …. [again].”

Gui Minhai the poet and free speech advocate: Bei Ling, Chinese exiled poet

How did you and Gui Minhai meet each other? “We met each other around 1984 when he was a university student at Beijing University. He just knocked on my door…He was very simple, and very young and a little shy… he wanted to show me some of his poems. We became very good friends, He always followed me to underground [writers’] salons; I introduced him to [lots of people, such as embassy staff, painters, writers and poets]. “We probably left China at the same time – I went to the US and he went to Sweden. He was working for some official publishing house. After he left China and I left China we didn’t meet each other until 2004 in Hong Kong. We lost connection, so many things were happening.”

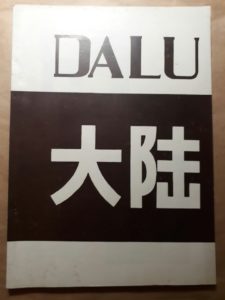

Cover of Dalu (Continent), an underground poetry journal from the 1980s with a copy of one of Gui Minhai's early poems titled "Longing for Greece", credit: Meng Lang (孟浪). Can you tell us a bit about how you were reunited in Hong Kong in 2004? “It was very emotional. He had totally changed. He was no longer shy and his whole body was bigger… Then we became good friends again, we always saw each other. I got a chance to visit his family in Germany. We saw each other in Hong Kong, I invited him to a literature congress in Taipei, and we saw each other at the Frankfurt Book Fair… "He cared about freedom of expression – especially in 2009. At the Frankfurt Book Fair, he supported me, in the same panel. But I do not know how involved he was with democracy but I think because he was a publisher, he cared about freedom of expression." Why do you think he began publishing books about China? "I think he got into publishing because he used to work for an official publishing house in Beijing as an editor… He had the experience, the training and the personal interest. He wanted to publish some politically sensitive books so [that’s probably why he wanted to open his own publishers]… "Before, he wrote scholarly works, then he wrote literature essays, later some publishing house asked him to write some politically sensitive books, about China. He was a very ‘eager’ person – he wanted to be number one… Later he wanted to publish books himself. The older publishers were very unhappy, and there was so much fighting. So many stories. If you want to know about him you have to spend several months interviewing lots of people in Hong Kong." What kinds of things did you do together? "He liked smoking, a little bit of drinking. We talked about publishing, political things, about the PEN Centre case and about Liu Xiaobo in jail and his Nobel Prize and underground literature… "He’s not a strong guy but he’s a smart guy. He knows how to play games with the government. .. He’s a very smart writer…"

Cover of Dalu (Continent), an underground poetry journal from the 1980s with a copy of one of Gui Minhai's early poems titled "Longing for Greece", credit: Meng Lang (孟浪). Can you tell us a bit about how you were reunited in Hong Kong in 2004? “It was very emotional. He had totally changed. He was no longer shy and his whole body was bigger… Then we became good friends again, we always saw each other. I got a chance to visit his family in Germany. We saw each other in Hong Kong, I invited him to a literature congress in Taipei, and we saw each other at the Frankfurt Book Fair… "He cared about freedom of expression – especially in 2009. At the Frankfurt Book Fair, he supported me, in the same panel. But I do not know how involved he was with democracy but I think because he was a publisher, he cared about freedom of expression." Why do you think he began publishing books about China? "I think he got into publishing because he used to work for an official publishing house in Beijing as an editor… He had the experience, the training and the personal interest. He wanted to publish some politically sensitive books so [that’s probably why he wanted to open his own publishers]… "Before, he wrote scholarly works, then he wrote literature essays, later some publishing house asked him to write some politically sensitive books, about China. He was a very ‘eager’ person – he wanted to be number one… Later he wanted to publish books himself. The older publishers were very unhappy, and there was so much fighting. So many stories. If you want to know about him you have to spend several months interviewing lots of people in Hong Kong." What kinds of things did you do together? "He liked smoking, a little bit of drinking. We talked about publishing, political things, about the PEN Centre case and about Liu Xiaobo in jail and his Nobel Prize and underground literature… "He’s not a strong guy but he’s a smart guy. He knows how to play games with the government. .. He’s a very smart writer…"

"[The only way to free Gui now] is not only one country, internationally – everyone – civil society, the German government, the US government, [everyone must call for Gui’s release]." Bei Ling

Was he worried about his safety before he was kidnapped by the Chinese state in 2015? "Gui did not realise that he could get into trouble in Thailand – he may have thought it would be sensitive in Hong Kong, but he never thought that he would have trouble in Thailand. If he knew this he probably would not have got in that car with those people [the Chinese agents who drove him away from outside his Thai apartment.]" How can the international community help Gui Minhai now? "It will be very difficult for him to leave China because the government doesn’t want him to say what happened to him [when they kidnapped him in Thailand in October 2015]. I’m very sure the Swedish government know these details now and that is why China is very unhappy [with Gui]. "[The only way to free Gui now] is not only one country, internationally – everyone – civil society, the German government, the US government, [everyone must call for Gui’s release]."

Gui Minhai, friend and writer on Nordic mythology: Magnus Fiskesjö, scholar at Cornell University

How did you and Gui Minhai meet each other? “I remember first meeting Gui Minhai in the mid-1980s, in Beijing, where he was a member of the new generation of poets and artists who were writing poetry and holding poetry readings. I knew him by the name Ahai, the pen-name he used. I remember him as a very cheerful and fun person. It's been many years since that time, so I don't remember every detail, but later I helped him apply to go to Sweden to study, and he completed a Master's degree at Gothenburg University, with a thesis that was later published in English in Copenhagen (NIAS, Nordic Institute for Asian Studies, 1992) [on] Chinese Marxist historiography…” When he lived in Sweden what kind of books did Gui Minhai write? “He was very interested in Sweden and Scandinavian culture, and he also wrote very interestingly about Scandinavia for Chinese audiences, including a book on Scandinavian mythology published in Chinese on the Chinese mainland.” When was the last time you saw him? “We sometimes corresponded, but later, over the years, I had infrequent and occasional contact with Gui. When I visited Hong Kong in 2012, we had a fun reunion with him and several other friends… I don't remember many details from that dinner. [But] I do remember that we both had put on weight! He was still his jovial, fun, old self.”

Gui Minhai, the smart businessman: Lam Wing-kee, colleague and Hong Kong bookseller

Lam Wing-kee gives a press conference in June 2016 about his kidnapping and time in Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location in China. Credit: screenshot from HKFP.

Lam Wing-kee gives a press conference in June 2016 about his kidnapping and time in Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location in China. Credit: screenshot from HKFP.

How did you and Gui Minhai meet each other? “I first met Gui more than ten years ago; he came to my store with some friends and came back several times. He established Mighty Current publisher around 2003 and as well as writing books himself, he paid friends from mainland China and North America to write for him.” What kind of books did Gui Minhai write? “If you want to understand Mr. Gui you need to understand his past. I heard that he graduated from Beijing University and was writing poems early on... and then he got into business... "He published nearly a thousand books after launching his publishing house.. He struck me as a smart businessman, nothing more." Why do you think Gui was singled out for the harshest treatment in the Hong Kong Booksellers case. “I believe it is related to Gui’s attempt to publish a book on Xi Jinping’s love life. This book included a copy of a ‘self-criticism’ Xi is [alleged] to have written while he was a governor of Fujian province for the Central government. You can say, that this book caused this bookshop incident; and all of us became funerary objects. “[After more than] two years being disappeared, Gui’s endurance must be stronger than mine. At least he is originally from the mainland and so more familiar with the situation and system there...

"You can say, that this book caused this bookshop incident; and all of us became funerary objects."

“I heard Cheung Jiping and Lui Bor [two other Hong Kong booksellers who were abducted in 2015] can’t come back to Hong Kong, but they are free to move around and work on the mainland. Lee Bo [the third bookseller] is free to come and go but not to talk to media. “I think that it will be harder for Gui to leave the country [now] unless more western countries and human rights NGOs call for his release.”

Final word: Since Gui Minhai's second kidnapping in January in front of two Swedish consular officials and his third staged confession on 9 February there has been no news of his fate. He remains in custody -- presumably at the Ningbo Detention Centre. Chinese authorities say he is being held on suspicion of leaking state secrets. Sweden continues to ask for access to see him.