Gui Minhai’s last days in Thailand

[Updated Oct 17, 2025] Some 10 years - or 3650 days - ago, Swedish publisher Gui Minhai was kidnapped from Thailand by Chinese state agents. He’s now serving 10 years in prison on charges of “illegally providing intelligence overseas". The Swedish government has had no contact with him since his sentence, and China has, in violation of its own Nationalities law, stripped him of his Swedish citizenship and given him his original Chinese citizenship back.

Today, the Swedish Foreign Minister, while visiting her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, publicly called for his release. She failed to point out that the manner in which Gui had had his Chinese nationality reinstated would be impossible using established legal procedure, hence that it is illegal. The Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson simply responded that the case has been handled "in accordance with the law".

--

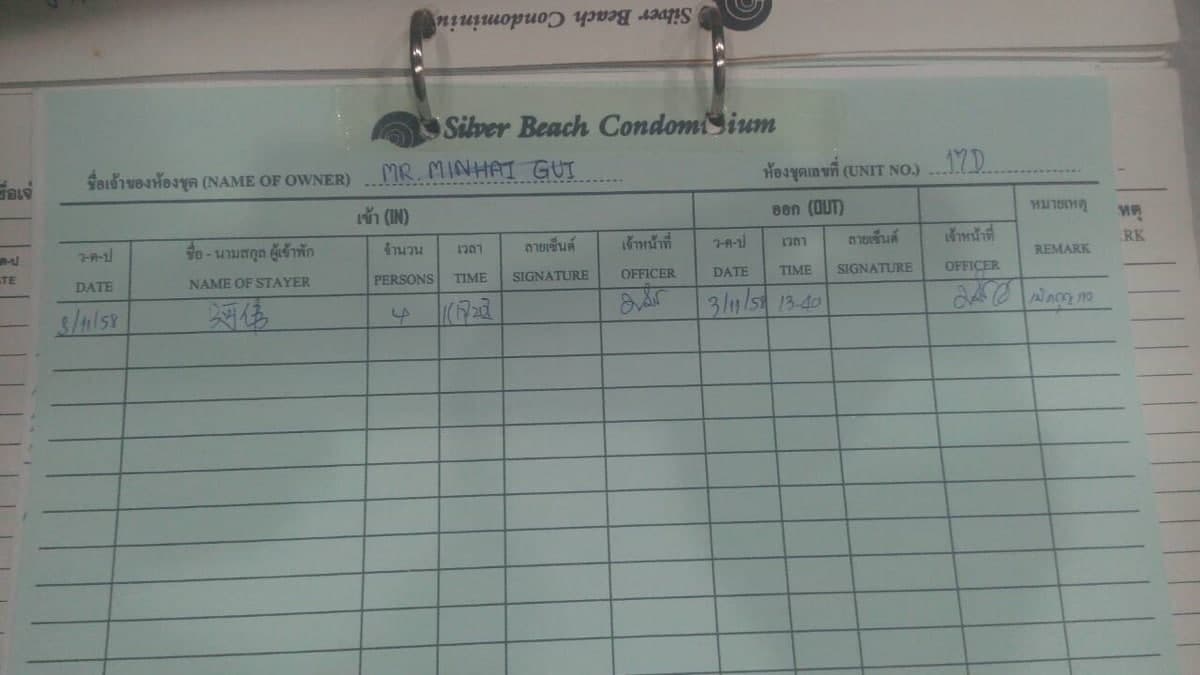

When Gui Minhai left Hong Kong on 6 October 2015, he thought he was simply going on a writing trip to his holiday home in Thailand. He had arranged for his Hong Kong apartment, walls stained by his incessant smoking, to be renovated. Gui was not a permanent resident of Hong Kong, and these trips also served as visa runs. After a four-night stopover in Bangkok, he arrived at his second home -- the Silver Beach Condo in Pattaya. His apartment, D, on the 17th floor boasts impressive views of the Gulf of Thailand. Days later he told his colleague Lee Bo, a UK citizen - who would later be kidnapped in Hong Kong - that he would be back in the city by 25 October as he had some visitors arriving.

But Gui would never go back to Hong Kong.

A brief recap of key moments is available in this video compilation. What happened to Gui Minhai – In Video

So what happened in those two weeks between Gui disappearing from his Thai home and when he surfaced in China? Amidst rumors, unverified information, and various people’s fanciful ideas, there is actually a fair amount, never properly presented. Even Gui’s own poetry can help us get closer to the truth.

So what happened in those two weeks between Gui disappearing from his Thai home and when he surfaced in China? Amidst rumors, unverified information, and various people’s fanciful ideas, there is actually a fair amount, never properly presented. Even Gui’s own poetry can help us get closer to the truth.

After having been in Pattaya for almost exactly a week, on 17 October, Gui returns by car from a morning shopping trip. Shortly before Gui returns, a Chinese man arrives at his Condo, a building, like most condos, protected by a guard station and gate. He talks on his phone in Chinese and then talks in bad Thai with the guard. The man then waits for Gui.

When Gui arrives, it’s a quarter past one. He drives past the entrance, later stopping to speak to the mysterious man. The timing of the man’s arrival seems odd until one realizes that Gui was using the Chinese social media app WeChat, and was easily traceable at all times because of it. Agents would have known his exact whereabouts no matter what.

When Gui arrives, it’s a quarter past one. He drives past the entrance, later stopping to speak to the mysterious man. The timing of the man’s arrival seems odd until one realizes that Gui was using the Chinese social media app WeChat, and was easily traceable at all times because of it. Agents would have known his exact whereabouts no matter what.

Gui asks the security guard to take care of his groceries – indicating that he expects to come back. The unidentified man, captured on security camera by the gate and guardhouse, wearing a striped shirt, gets into his car, and together they drive off. After this, his many phone calls to the people renovating his home back in Hong Kong stops abruptly.

We don’t see Gui again until exactly three months later when he appears in a forced TV confession in China, 17 January, early next year. The footage is beamed around the world, including in Sweden, where Swedish officials are duly humiliated by their inability to protect or even stand up for one of their own citizens. A day after the TV broadcast, Swedish police say that Thai immigration claims to have no record of Gui ever leaving Thailand.

--

Rewind back three months. Gui has just driven off. His car, a white Honda CR-V, license plate บจ 5870, is nowhere to be found (and is still seemingly remaining missing). Shortly afterward he calls Mai (Suriya [xxxxx]porn), the manager of the condo, and asks if they can put his groceries, left with the guard, into his fridge. He also asks her to lock all his windows and his door. Something has changed. It now looks like he thinks he might be some time before being able to go home.

A little more than two weeks after that happened, on a Tuesday afternoon, 3 November, four men appear at Gui’s condo. We know that at least three of them speak Chinese but the man in the striped shirt is not among them. Their apparent leader, in a red shirt, makes a call while they are all outside the gate. Soon after Gui phones property manager Mai and gives them permission to enter, and to stay the night (they don’t). The leader sign in using the name, 何伟. The characters are in simplified Chinese indicating they are likely from mainland China. [The police report later filed dates the phone call from Gui to Mai to November 2, one day before the four men arrived.]

The phone number from which Gui called, +783 8182216, is later in October no longer in service and is seemingly an internet number.

When the condo manager asks them where Gui is they say he is in nearby Cambodia gambling, and won’t be back for a while. Two of those statements are almost entirely sure to be true; that he was indeed in Cambodia and that was not coming back anytime soon.

When the condo manager asks them where Gui is they say he is in nearby Cambodia gambling, and won’t be back for a while. Two of those statements are almost entirely sure to be true; that he was indeed in Cambodia and that was not coming back anytime soon.

CCTV videos show that the men spend 26 minutes in his apartment, but is prohibited from taking Gui’s large stationary apple computer. They move quickly to turn on his computer. When they leave, CCTV shows them empty-handed, but no one has been able to find Gui’s travel documents so it’s possible they took them. They are not allowed to bring his computer. However, it is possible that his hard drive was copied.

It should be noted that Chinese police took a significant risk letting Gui’s co-worker Lam Wing-kee, who was also held in secret detention for a prolonged period, out of China and back into Hong Kong in mid-2016, for the sole purpose of having Lam retrieve the computers from their office in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong. In the end, Lam instead refused to go back as promised and held an explosive press conference that laid bare the Chinese police operation.

After the men left, fruit piled high in a bowl is left to rot and a large package from his colleague in Hong Kong with copies of one of their new books remains unopened. A finished book Gui never got to read.

At 13:44, the four men leave in a car outside the Condo. Later that day call Mai, apparently while in a taxi, to say they left the A/C on. The phone they used is left in the taxi, either intentionally or by accident. It’s a local sim card.

The next day, 4 November, the dissident-run news website Boxun runs a small story about the possible disappearance of Gui. A story that is noticed by Chinese dissidents abroad, but goes virtually unnoticed by everyone else.

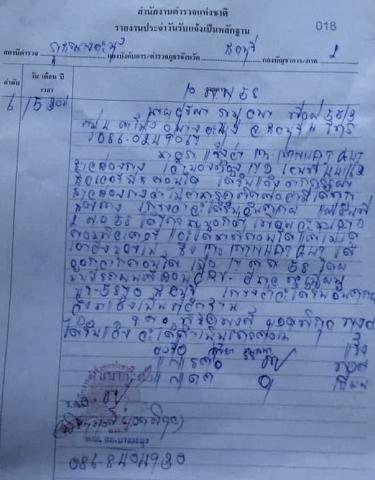

On 10 November Mai contacts the local Bang Lamung district police and Police Captain Pichitpong Yodpikul accepts the police reports, says it will follow up in accordance with set procedure, and signs it.

After people start calling and looking for Gui, Mai tries to contact the men who had gone into his flat. She calls up the phone the men used to call her earlier about forgetting to turn off Gui’s A/C. A local Pattaya cab driver, now in the Thai-Cambodian border area of Poipet picks up. The driver says that he had driven the men to the border town, a Wild West type area famous for prostitution and gambling. Later on, this number would go dead. But as the story of Gui’s disappearance starts growing, she later gets a call from Gui, who claims he is fine but then hangs up when Mai asks him more questions. These phone numbers are all registered to far-flung places, almost certainly internet phone numbers. By December, when these are tested, the numbers have all been disconnected.

There is now a real fear that something has happened to Gui. Quickly, Gui’s friend Bei Ling, another Chinese exile living in the US and Taiwan, asks two of his friends in Bangkok to go to his home and find out what happened. They meet with the manager and enlist her help in trying to find Gui, including getting access to the CCTV footage in the compound. On 8 December, The Guardian blows the story wide open with a larger piece, including photos of Gui’s flat.

--

At first, some people fear that that Gui was put on a chartered flight out of Bangkok together with two (UNHCR-protected) dissidents (Jiang Yefei and Dong Guanping) and two Falun gong practitioners, on 13 November. Later, after one of the Falun Gong practitioners and one of the dissidents were released from prison, they confirm that Gui was not on their flight. This rumor persists for a long time.

More likely than the above, Gui was perhaps illegally forced back to China on a 9 November flight out of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh. That day, four planes, chartered by Chinese police, took 254 people that had been rounded up in operations in Indonesia and Cambodia back to China. The coincidence of both time and place is striking, making many believe that Gui was on one of those flights.

Poipet, the hellish border town, is not just famous for its gambling – illegal in Thailand – but also a place where anything can be bought. A perfect place to smuggle Gui out of Thailand by bribing a guard or by sneaking him across one of the many small bamboo bridges that cross the tiny river that mark the border. This could explain why there is no official record of Gui having left Thailand. The other option, that Thai authorities are lying and have erased the record seems far less likely.

It’s a mere three to four hours’ drive from Gui’s home in Pattaya to Poipet. You would need to take highway 331 and then switch over to 351, all the way to the border. It is now almost certain this was how he left Thailand. This was the road taken by the four men after visiting his apartment and try to take his computer. The agents weren’t lying when they told the condo manager that Gui was in Cambodia, only that he wasn’t there to gamble.

We know with some certainty that by 13 November, he was already in China. That day he called his daughter on Skype. But, instead of speaking in Swedish as they would normally do, the entire conversation was in English. This way, the police, or more likely, Ministry of State Security (MSS) agents, almost certainly listening in, could ensure they would understand the conversation and he would keep to the script designed for the call. Languages outside of Chinese or English not allowed during such communication, nor in communication with consular officials either. The police or MSS must always be able to know what is being said.

So how did he make it back to China without being spotted or there being any official record of him leaving Thailand? Gui has given us some clues as to how this happened. And it’s also the way that many Chinese dissidents have escaped China – across the Golden Triangle that spans China, Laos, and Myanmar.

Gui was probably driven across northern Cambodia, a seven-hour drive to the border with Laos at Si Phan Don. There he was forced onto a small boat that would have slowly moved north along the long and winding Mekong River.

Later on, he shared a poem with his daughter, in which he alludes to such a journey. He made the same hints in several phone calls they shared. Called, ‘A night by the Mekong River’, he speaks of being ‘captured’ by the banks of the river, traveling upstream, often by night.

He may have tried to escape when he realized that he was running out of chances as they got closer to China; he writes about being beaten, tied up, and have a hood placed over his head.

Gui has never before many any such journey. In the poem, he wonders when he will pass Luang Prabang in northern Laos, a city he has indeed visited before. And about how he will travel toward Myanmar. The poem doesn’t describe what happens then. Likely they switched to a car since the Mekong becomes difficult to navigate close to China in the final stretch near to the notorious golden triangle area, although it is possible he was indeed smuggled into China by boat.

How he really did the journey is something that we will likely not know for a long time, for the simple reason that Gui’s kidnapping, his enforced disappearance, and torture are all “state secrets”. And these are the very “state secrets” that he is now in prison for.

--

Despite pleas to Thai police from several different friends of Gui’s to actively pursue this, the promise made to Mai, when she filed her police report on 10 November, seemingly went nowhere, and there are no further words from any findings from the Thai police.

By the time Guardian journalist Oliver Holmes visited his apartment – almost a month and a half after Gui disappeared – no Swedish or Thai police had visited or even called the condo. On 20 November, Swedish police said they would dispatch investigators, but seemingly nothing happens.

In fact, confirmation that there are no records of Gui ever leaving Thailand is made public only the day after his televised confession, on January 17 the next year (2016) – the first time most people learn what has happened to him. By this time - three months after his disappearance - Swedish police have still not visited the condo. Nor called it. Nor have they called the Guardian journalist who did visit. Or any of the others who had by this time been there and provided information.

It takes 10 days after Gui has been paraded on TV, globally, to the humiliation of the Swedish Foreign Ministry, for the police to arrive at his apartment in Thailand, by which time its 27 January – 102 days after his kidnapping. At this point, an iPad goes missing, likely taken by Swedish police – but his computer, there earlier in December, is by now already missing. Who took it no one knows, but management claims a long list of people has visited the apartment over the months. What happened to Gui’s expensive car, which he left with, also remains a mystery to this day.

Before Gui was re-arrested in dramatic fashion 20 January 2018, as reported by the Guardian, he spent some time living under house arrest, with limited freedom, but did manage to meet with consular officials at the nearby Swedish consulate in Shanghai. During one of these meetings, he shared as many details as he could about what actually happened to him. Despite this, the Swedish Foreign Ministry has chosen to not use this explosive information in public, in yet another failed attempt at quiet diplomacy, one that seemingly, over five years, have borne little fruit. Friends and family alike have been told more or less nothing by the Foreign Ministry about the reality of his capture, kidnapping, disappearance, and strange reappearance in a Chinese detention center.

--

We would like to thank Angela Gui, Bei Ling, Magnus Fiskesjo, Oliver Holmes, and Sheng Xue for helping piece together as much information as possible about Gui’s last days in Thailand. CCTV video recordings, visitor log from Condo, and photo of the initial police report filed provided courtesy of Li Fang. Photo of Gui’s apartment provided courtesy of Bei Ling.

To learn more about China's use of forced televised confessions - and to support our work in exposing it - buy our groundbreaking report Scripted and Staged on Amazon worldwide (also available for free as a PDF here), or our book, Trial By Media, also available on Amazon worldwide.