How China censors Covid conversations with arrests, threats & disappearances

As China wages a political influence campaign overseas on Covid-19, at home it has intensified control of the spread of information, media and free speech to ensure no voice undermines or even brings nuance to its state-sanctioned version of events. Beijing has come under fire for delaying important information on the virus in the early weeks from the rest of the world, so it is no surprise that the censorship effort has been especially vigorous this time.

As China wages a political influence campaign overseas on Covid-19, at home it has intensified control of the spread of information, media and free speech to ensure no voice undermines or even brings nuance to its state-sanctioned version of events. Beijing has come under fire for delaying important information on the virus in the early weeks from the rest of the world, so it is no surprise that the censorship effort has been especially vigorous this time.

China has used Covid-19 to disappear journalists, doctors and those who write or post comments that spar with the official narrative.

Now even people who comment online about these disappearances are themselves starting to disappear.

Safeguard Defenders has been tracking the variety of approaches being used by Chinese authorities, including enforced quarantine, arrest, disappearance into Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) and RSDL’s Party-State equivalent, Liuzhi, and forced public confessions.

Disappearances

Many of those who were disappeared have reemerged weeks or months later arrested (see below). Several were placed into Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). This is a feared custodial system that was introduced in 2013. Victims are “disappeared” to a secret location, kept in isolation and incommunicado from family, friends, or any legal counsel, for a period of up to six months. RSDL is used widely on rights lawyers and activists, and has been called “tantamount to an enforced disappearance” by the UN Committee Against Torture.

In April, Chen Mei, an NGO worker, Cai Wei, a tech company staffer and Xiao Tang (Cai’s girlfriend) disappeared from Beijing. A few weeks later, it emerged that Chen and Cai were being held under RSDL, accused of “picking quarrels & provoking trouble”. All three had taken part in a project called Terminus2049 that archived stories on the coronavirus outbreak on Github as they were being scrubbed off the Internet by censorship directives from Beijing. After six weeks in RSDL, Chen and Cai were moved to Chaoyang District Detention Centre and formally arrested, according to detention notices sent to their families. There are reports that their families have not been allowed to appoint lawyers for them. There is no media report of Xiao Tang’s whereabouts.

For Party members or workers for the state there is a custodial system called Liuzhi that works just like RSDL. It amounts to an enforced disappearance and places the victim at high risk of torture and mistreatment. It is run by the National Supervision Commission (NSC).

Property tycoon and Party member Ren Zhiqiang, wrote an essay calling Xi Jinping a power-hungry “clown,” criticized the handling of the virus outbreak and published it on Chinese social media site. He disappeared on 12 March. On 7 April, it emerged he was being held by the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) for “serious violations of law and discipline.” It’s most likely he is being held under liuzhi.

Arrests

Citizen journalist, activist and former lawyer Zhang Zhan was livestreaming on Twitter and Youtube her reports from Wuhan, some of which was critical of government measures to control the virus. She disappeared 14 May. More than a month later, on 19 June, her family were informed that she has been formally charged for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble”. She is now being held in detention in Shanghai.

Activist Xie Fengxia (also known as Xie Wenfei) was detained and charged at the end of April in Hunan province with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” In the days before his arrest he had criticized the detention of Chen and Cai (above) and the disappearances of Fang Bin and Chen Qiushi (see below).

Retired professor Chen Zhaozhi, who called COVID-19 a “CCP virus” online, was detained 10 March and formally arrested 14 April for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” He is being held at Haidian Detention Centre in Beijing. Some reports say he suffers from Alzheimer’s.

Perhaps most serious is the case of Guo Quan, a former professor at Nanjing Normal University and a human rights activist. After he published online essays critical of the government’s handling of the outbreak online in January, he was arrested on 14 February, charged with “inciting subversion”. He is being held at Nanking No.2 Detention Centre.

Enforced quarantine

Li Zehua, a citizen journalist and former CCTV presenter, was using Weibo, YouTube and Twitter to upload videos of the Wuhan coronavirus situation including reports on alleged cover-up of cages and a video of a crematorium. He suddenly disappeared on 26 February. He reappeared 23 April in “confession” style video, saying he had been forcibly put under quarantine by police in Wuhan and then later in his home town. See here for our story on Li.

Forced Confessions

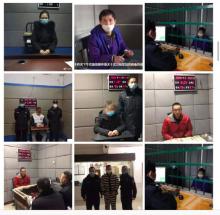

China also brought out a well-worn tool – public forced confessions -- to control the debate on the disease and humiliate and punish those who “spread rumours” or share unauthorized information. In most of these cases the police posted confessions they had filmed on their official Wechat or Weibo platforms.

China also brought out a well-worn tool – public forced confessions -- to control the debate on the disease and humiliate and punish those who “spread rumours” or share unauthorized information. In most of these cases the police posted confessions they had filmed on their official Wechat or Weibo platforms.

The targets are predomiantly ordinary people who had just posted about something they’ve heard or seen, rather than citizen journalists, activists or intellecutuals. This nationwide campaign to "refute the rumours" – which was at its peak in January – frightened people into thinking twice about discussing the disease on the Internet, and showed that if you get caught, not only can you be punished but you will be paraded humiliatingly online. While most of their their faces are obscured on camera, several of them are shown locked into a tiger chair.

In our research we found many dozens of victims. Our story here profiles six victims, three in Hainan, one in Sichuan and two in Jiangxi provinces. Their confessed “crimes” varied from hiking rice prices on rumours of Covid-related food shortages to a man who posted a video of hospital workers wearing PPE and writing a caption that said Covid had reached his town.

In one case, Li Zehua (above), published a video to his own social media that had all the hallmarks of being a type of forced confessions. Some of the comments he made – praising the police, for example – were very different in tone and attitude to his previous posts.

Still Disappeared

While many crackdowns begin with the police kidnapping their victims, usually they remerge later, either released or in detention and charged with a public order crime, or more seriously, national security crimes even if their only action has been to post something on social media. The following people remain disappeared, either still in the hand of authorities, or released but too scared to speak to media.

Fang Bin, a citizen journalist and Wuhan businessman has posted video of corpses on Youtube. He was last heard from on 9 February. As of 25 June, he remains disappeared.

Fellow citizen journalist, and former human rights lawyer, Chen Qiushi, had been uploading videos from hospitals and conducting interviews with medical staff in Wuhan. He disappeared on 6 or 7 February. Like Fang, he remains disappeared.

Tsinghua University law professor Xu Zhangrun disappeared shortly after he published an essay online, titled, “When Fury Overcomes Fear,” which criticized how China had handled the coronavirus pandemic and urged for freedom of speech. A Dui Hua report earlier this year said he had been placed under house arrest.

Doctor at Wuhan Central Hospital Ai Fen gave an interview in early March with Chinese People magazine confirming hospital did quash early reports of the outbreak. She disappeared in mid-March and hasn’t appeared in the media since then.

Several doctors in Wuhan were criticized and forced to sign a confession by police in December last year and early January for speaking out about the virus, including the famous whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang, who tragically died of the disease in February. See our story on Dr Li here.