New data exposes increased use of NSC's Liuzhi system

Recently, Safeguard Defenders released an investigation into how the UNODC agency is cooperating with China's non-judicial organ the National Supervision Commission (NSC). Related to that, new data on the use of secret detentions, liuzhi, by the NSC was filed to relevant United Nations bodies. The information on the NSC's use of liuzhi is here published in stand-alone form for ease of access.

The NSC and its mass use of disappearances to fight “corruption”

Based on the one-year pilot project before the NSC’s launch, it has mandate to investigate a group of up to 300,000,000 people. The system - operating outside any judicial bounds, and which is not a judicial organ, nor does it have, in theory, any relation to the investigation of crimes as such – was created to expand the scope of supervising and ‘controlling’ not only party members, state functionaries, management at schools, hospitals, universities, mass organizations, and state-owned enterprises, but also journalists, business people, and local contractors.

The system, which employs mass use of enforced disappearances and torture, and undermines any chance of a fair trial, was denounced by Safeguard Defenders on the International Day of the Disappeared in 2019 and a comprehensive review of the system was provided to the relevant UN organs at that time, along with a call to review the system and condemn any and all practices found to be in violation of key human rights protections. A new submission was made in 2021, with added data.

Depending on which statistic from the Chinese government is used - a minimum average of 16 to 76 people are put into the NSC’s liuzhi detention system, every single day. Once placed into the system, the victim can be held for up to six months, without the right to consult a lawyer, without the right for judicial review, without contact or information to family members. There is no external appeal or redress possible. At all. Even when the NSC clearly violates the law and keeps the suspect beyond the time limit of six months.

Depending on which statistic from the Chinese government is used - a minimum average of 16 to 76 people are put into the NSC’s liuzhi detention system, every single day. Once placed into the system, the victim can be held for up to six months, without the right to consult a lawyer, without the right for judicial review, without contact or information to family members. There is no external appeal or redress possible. At all. Even when the NSC clearly violates the law and keeps the suspect beyond the time limit of six months.

The system closely resembles the Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location custodial mechanism, which the UN Human Rights Mandates have called a form of enforced disappearance - except that it does not form part of any criminal procedure, and stands entirely outside the judicial system.

Once inside, the victims are simply and literally disappeared.

Liuzhi is a legalized system for disappearances. It came into effect in 2018, under the NSC and operates with total impunity. It is not a judicial organ, and those taken away and disappeared are not part of any judicial process. The investigators are not classified as judicial personnel, and therefore they are excluded from already non-effective anti-torture provisions in Chinese law. The victims must be kept at secret facilities outside the judicial system. The NSC has also been explicitly classified as “a non-administrative organ”, which renders it immune from any lawsuits based on China’s administrative law. This grants it complete im(p)unity for any wrongdoing it may be responsible for. In fact, it is also tasked with investigating police, prosecutors, and courts for malpractice, which in practical terms expands on its impunity even further, as no judicial organ would dare go against the NSC.

Liuzhi is a legalized system for disappearances. It came into effect in 2018, under the NSC and operates with total impunity. It is not a judicial organ, and those taken away and disappeared are not part of any judicial process. The investigators are not classified as judicial personnel, and therefore they are excluded from already non-effective anti-torture provisions in Chinese law. The victims must be kept at secret facilities outside the judicial system. The NSC has also been explicitly classified as “a non-administrative organ”, which renders it immune from any lawsuits based on China’s administrative law. This grants it complete im(p)unity for any wrongdoing it may be responsible for. In fact, it is also tasked with investigating police, prosecutors, and courts for malpractice, which in practical terms expands on its impunity even further, as no judicial organ would dare go against the NSC.

In the establishment of the NSC, the former Ministry of Supervision, the Procuratorate’s anti-corruption bureau, and the National Audit Office were merged. All these bodies handled investigations of economic crimes by state functionaries. The Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) – which has long been tasked with both ‘discipline inspection’ and investigating economic crimes by party members continues to exist alongside the NSC, in effect the same body but with two different names.

Before the establishment of the NSC, any investigation for a breach of law, including for economic crimes, had to be investigated and pursued through the legal system, unless the suspect was a member of the Chinese Communist Party. By creating the NSC, the judicial system no longer has the right to investigate such crimes but must hand cases over to the NSC for investigation, allowing exclusive competence for presumed violation of duties and economic crimes to this non-judicial organ operating outside any legal bounds.

In the words of Zhejiang province’s anti-graft chief Liu Jianchao: "These are not criminal or judicial arrests and they are more effective.” Jiang Mingan, a Peking University law professor elaborated further: corruption cases are "heavily dependent on the suspect’s confession. (...) If he (the suspect) remains silent under the advice of a lawyer, it would be very hard to crack the case".

In sum: an extra-judicial ’anti-corruption’ body on steroids, created to legalize mass human rights abuse and instill fear in the hearts and minds of the CCP’s subjects.

New data on the mass use of Liuzhi

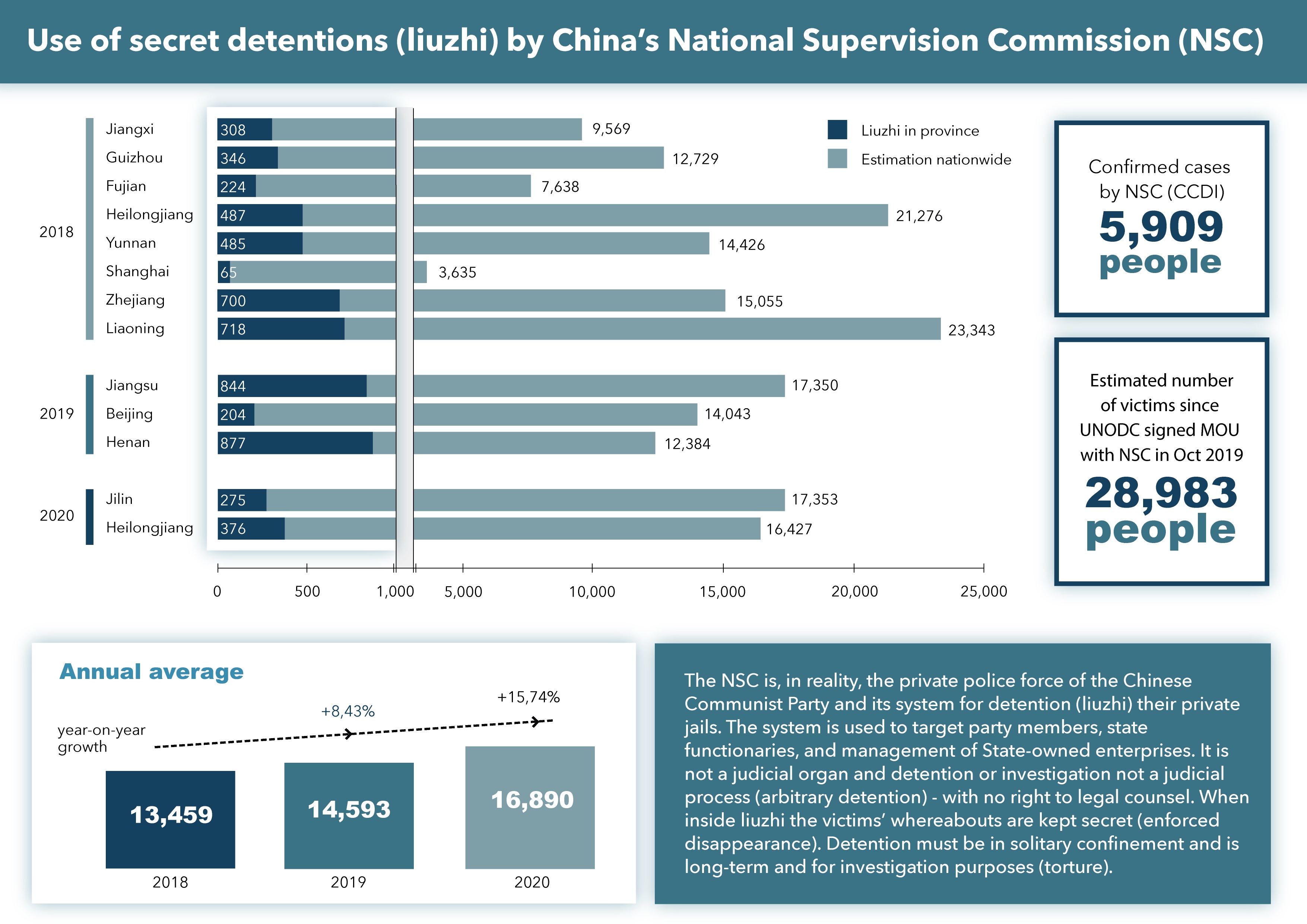

Even though the government intentionally does not release nationwide data on liuzhi use, and many times only fragmented data from select provinces is made available, and not always for entire calendar years, there is nonetheless data available. Since 2018, the following data, per province, has been released (column Liuzhi in province):

Sources: See tables and list of sources in the appended UN submission, or download directly by clicking here.

Even though there are only a few data points, especially for 2019 and 2020, based on extrapolation, one can calculate nationwide figures based on each provinces’ level of (admitted) use of liuzhi (column Estimation nationwide based on Liuzhi in province and province’s % of total population). The calculations allow to infer some averages nationwide, as shown above.

In fact, even without any extrapolations, or attempts to gain nationwide data, the above data from the NSC itself still admits to 5,909 cases of liuzhi in the select provinces during the period. As this comes from the NSC itself, those 5,909 cases are irrefutable. As the NSC is not a judicial body, and their investigations are not, by definition, judicial procedures, they are all by definition arbitrary detentions. The UN has, in addition, clearly laid firm that the use of solitary confinement, which is a prerequisite in law for liuzhi, amounts to both torture (article 1, CAT) and maltreatment (article 16, CAT) if it is a) prolonged (over two weeks) and b) performed during the investigative period and for investigative purposes. A detailed analysis released by SD of this is available.

Denial of knowledge to the family of the whereabouts of the victims, the lack of any right to access legal counsel, and that they are kept in non-judicial system facilities, and denied communication, also means, as ten Special Procedures of the UN has already established, ‘enforced or involuntary disappearances’.