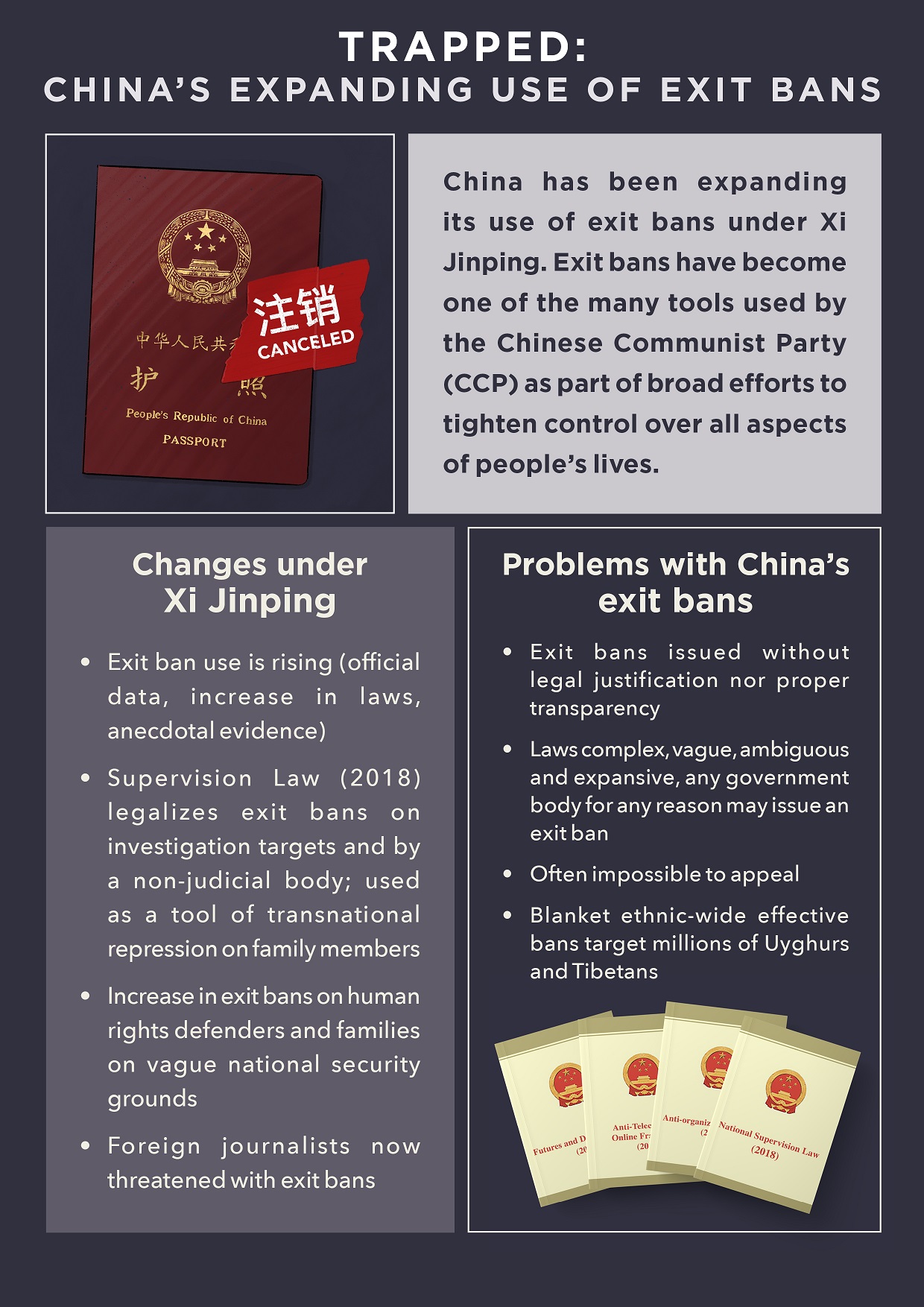

Trapped - China’s Expanding Use of Exit Bans

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been widening the legal landscape for imposing exit bans and is increasing their use against everyone from human rights defenders to foreign journalists.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has been widening the legal landscape for imposing exit bans and is increasing their use against everyone from human rights defenders to foreign journalists.

Safeguard Defenders’ new report Trapped: China’s Expanding Use of Exit Bans uses official data, an examination of new laws and interviews with victims to explore how the country is increasingly resorting to exit bans to punish human rights defenders (HRDs) and their families, hold people hostage to force targets overseas to come back to China (a practice called persuade to return, a form of transnational repression), control ethnic-religious groups, engage in hostage diplomacy and intimidate foreign journalists.

Download the report (PDF) here, or click on cover image above.

[Exit Ban: state-initiated ban on an individual from leaving the country, either at the border or by cancelling or confiscating their passport.]

Another exit ban law

Just last week, China approved new amendments to its Counter-espionage Law, that will allow exit bans on anyone under investigation (Chinese and foreigners) or on Chinese nationals if deemed a potential national security risk after leaving the country.

This means that between 2018 and July of this year, no less than five new or amended laws provide for the use of exit bans, for a new total of at least 15 laws.

In the absence of transparent official data and excluding ethnicity-based exit bans, which number in the millions, we estimate that at least tens of thousands of people in China are placed on exit bans at any one time. Many of these exit bans are illegitimate and violate the Universal Declaration of Human Right’s principle of Freedom of Movement.

Targeting HRDs

Anecdotal evidence points to an increasing use of exit bans on both HRDs and their family members - including young children - and cases where a family member is terminally ill.

In 2021, activist Guo Feixiong was prevented from leaving China to see his wife, Zhang Qing, who had been hospitalized in the US with cancer. Border guards told him that he was banned from leaving on national security grounds – a vague term often used as justification for harassing HRDs.

Guo then disappeared, only surfacing months later. As Zhang’s condition worsened, she wrote from her hospital bed:

“Never could I imagine the Chinese authorities were capable of such inhumane cruelty – to keep him locked up when my life is coming to an end.”

Zhang died in January 2022. Two days later police arrested Guo.

Persuade to Return

As part of the CCP’s expanding practice of transnational repression, family members are often held as hostages in China with exit bans to force a target to return to China. Sometimes the target is an individual under investigation for economic crimes, sometimes they are political targets, including HRDs.

One of the latest cases to emerge is that of Xie Fang, the wife of Yu Miao, the former owner of a Shanghai bookstore that sold titles on politics and law. After the bookstore was forced to close down in 2018, the couple relocated to the US with their children. Xie, who went back to China to visit her sick mother in 2022, has not been allowed to leave the country since. Police said they would only remove her exit ban if her husband, who they suspect of posting articles online from the US, came back to China.

Foreigners have also been targeted under persuade to return operations. Americans Daniel Hsu and siblings Cynthia and Victor Liu were given exit bans to force their fathers, who were suspected of economic crimes, to come back to China. Such exit bans can linger for years. Hsu was prevented from leaving for four years, the Lius for three. None of them was legally connected to their parents’ suspected crimes.

Business disputes

Dozens of foreigners are also being prevented from leaving China if they work for a company that is involved in a civil dispute. Deliberately vague wording in the Civil Procedure Law means that individuals not even connected to the dispute can be trapped in China. Irish businessman Richard O’Halloran was barred from leaving China for more than three years (2019 to 2022) because the company he worked for was involved in a commercial dispute, even though he wasn’t even working for the firm when the dispute began.

In some cases, the targeting of foreigners is part of Beijing’s hostage diplomacy, a tit-for-tat retaliation aimed at a foreign government or a tactic to extract concessions. Often, the action is more serious, such as arbitrary detention, or sometimes exit bans are used in the initial stages. For several years now, the US State Department’s travel advisory on China has warned that Beijing uses exit bans to “gain bargaining leverage over foreign governments.” The targeting of some foreign journalists falls under this category.

Intimidating foreign journalists

Under Xi Jinping, exit bans are being weaponized to target foreign journalists. Since 2018, there have been at least four known cases of foreign journalists being targeted, or threatened with, exit bans, including BBC reporter John Sudworth and Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Matthew Carney.

No way to appeal

Many people find out they cannot leave the country only when they arrive at the airport. Often no reason is given, and channels to challenge the ban are either non-existent or ineffective.

In March 2023, police in Lvliang City in Shanxi province told Chinese activist Gao Xuqiang that they could not reveal why he was under an exit ban because it was a state secret!

Gao had earlier filed a Freedom of Information request to force the police to explain why he had been prevented from flying to Europe last year to attend a workshop. Border guards even snipped off a corner of his passport at the time.

He told Safeguard Defenders that in the beginning he felt: “desperate and helpless… my plans had been ruined.” Later he came to terms with it and decided to challenge the ban through the courts, a practice he says is “a relatively safer way to resist.”

Trapped, escape is the only option

Since exit bans can drag on for years, some human rights defenders have resorted to smuggling themselves out of the country in desperation.

In 2017, artist and activist Xiang Li escaped to Thailand after she was prevented multiple times from leaving China and her efforts to get an official explanation for why were ignored.

“I felt that I would be banned forever from leaving China so that’s why I decided to escape,” she told Safeguard Defenders.

Read Trapped: China's Expanding Use of Exit Bans here.

Download the Executive Summary here.