Rampant Repression: up to 30,000 disappeared in China’s RSDL jails since 2013

This is the shocking new statistic from our latest research and published today in a new report Rampant Repression (download as PDF here) that used official statistics and is itself an underestimate.

They are part of some 30,000 people who have been taken by police into 'Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location' (RSDL) since it was legalized in 2013. This feared custodial process places the victim at a secret location, in isolation, and held incommunicado for up to half a year. There is no lawyer or family access. There is virtually no oversight. Torture is common.

Until now there has been little attention paid on this system, in part because China is so secretive about its operations. That's why it is so important that as much data as possible is gathered and exposed to shed more light on this abhorrent system.

Using data from court verdict cases posted to the Supreme Court database, we estimated that at least 28,000 to 29,000 people were placed into RSDL by the end of 2019 since the system came into effect in 2013. Since official data only publishes cases with verdicts, the real number of RSDL victims is much higher, and perhaps significantly higher when we count those cases without verdicts.

In higher-profile cases, Safeguard Defenders found that RSDL, supposedly a tool for investigation, was used more often for punishment. Victims, often lawyers, journalists or NGO workers, are released from a lengthy stay in RSDL without their case going to indictment and trial. These cases never appear in the official data, thus the numbers in our report are an underestimate.

As the above graph attests, by 2022 or 2023, more than 10,000 people could be disappeared into RSDL in one year alone. This is mass state-sanctioned kidnapping.

It constitutes widespread and systematic use of enforced disappearances. In fact, enforced disappearances – essentially state-sanctioned or organized kidnappings – are considered so severe a human rights violation that according to international law the widespread or systematic use of enforced disappearances may constitute a crime against humanity.

Anecdotal evidence collected through interviews show RSDL victims are systematically denied access to legal counsel, families or friends are not notified as to where the person is being held – in many cases police even fail to provide the legally mandated notice that they have even been placed into RSDL at all. When police do not inform families (which appears to be the norm rather than the exception), the use of RSDL qualifies as an enforced or involuntary disappearance.

In 2018, ten United Nations Special Procedures, wrote to the Chinese government, following an earlier review of China’s RSDL use submitted by Safeguard Defenders, calling RSDL a form of enforced or involuntary disappearance.

This report also reveals other concerning aspects about RSDL:

- First, police often use facilities that are not legally allowed to be used for RSDL;

- A not insignificant amount of RSDL cases last longer than the legal limit of 183 days; and many last longer than the 15 days that constitute not only ill-treatment (Article 16) but torture (Article 1) under the Convention Against Torture because RSDL is a form of solitary confinement.

Thus, this report concludes that the average duration of RSDL detention points to the systematic and widespread use of torture. In addition, anecdotal evidence presented to the UN in 2018 (see above) and other research conducted by Safeguard Defenders show that RSDL often involves physical and mental torture perpetrated by the police against the victim.

The continued increase in the use of RSDL, and other systems for enforced disappearance in China, are concerning, particularly considering there is no sign of its slowdown.

RSDL is essentially state-sanctioned kidnapping, something once popularised by the South American dictatorships of the 1960s and 1970s. The world should condemn China for this abusive custodial system and take every measure to urge for its abolition, otherwise many more thousands of Chinese people will suffer and it may well be exported to other authoritarian governments, particularly in Southeast and central Asia.

Want to learn more about RSDL?

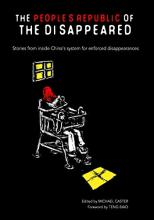

The People’s Republic of the Disappeared (2nd edition) includes RSDL victims’ own testimony of what goes on inside these secret facilities, as well as information on how China is expanding its use of different forms of disappearances, with a focus on the developments over the last two years, ranging from ad-hoc secret detentions, the new National Supervision Commission and the Liuzhi system, and mass disappearances of Uighurs in the Xinjiang region. It's available as a paperback or a kindle e-book.

The People’s Republic of the Disappeared (2nd edition) includes RSDL victims’ own testimony of what goes on inside these secret facilities, as well as information on how China is expanding its use of different forms of disappearances, with a focus on the developments over the last two years, ranging from ad-hoc secret detentions, the new National Supervision Commission and the Liuzhi system, and mass disappearances of Uighurs in the Xinjiang region. It's available as a paperback or a kindle e-book.