Trapped in Dubai – China’s hunt for a teenage dissident

Update: July 29: Wang and girlfriend Wu Huan are in Amsterdam in immigration detention, pending a decision on their asylum request.

Update: May 27: Wang Jingyu released from detention, deported back to Istanbul, Turkey, where he arrived from. He says he was handcuffed in the middle of the night and taken to the airplane and sent back to Istanbul. Given one (of two) phones and his passport. His computer, most clothes, etc, remain with Dubai police.

***

What started as a solitary, early evening post on China’s Weibo platform on February 21 earlier this year, questioning the PLA and the Chinese government after its conflict with India the year before, is rapidly turning into an international incident in a dramatic standoff between a lone teenage Chinese dissident and the Chinese State. At play is also the Dubai authorities, who in determining the fate of the teenager, will also seal the fate on whether Dubai, like Hong Kong, is to become yet another transit hub no longer safe for anyone that has questioned the Chinese State or its policies.

Wang Jingyu was only 17 or 18 years old when he left China, back in July 2019, and relocated to Istanbul, Turkey, after having offered public support for the anti-extradition protests in Hong Kong on Tiktok. In April this year, after having questioned the PLA and the Chinese State about hiding the death toll among Chinese soldiers following the June 2020 Galwan valley clash between China and India, and feeling the increased persecution of himself and his parents, he hastily booked a flight out of Turkey to the safety of the United States. He never made it to New York, his intended destination.

The capture of a teenage dissident

On April 5 armed with a first class ticket, Wang boarded Emirates flight ER122 from Istanbul to Dubai for a quick stopover of just under two hours before planning to continue to New York’s John F. Kennedy airport on ER203. As recent reporting has made clear, he never made his connection. At some point after arriving just before 1 AM on the morning of April 6, he was taken into custody by two plainclothes policemen. He spent the first 48 hours with immigration police near the airport before being transferred to the detention centre of Al Barsha Police Station, some 30 kilometres away.

Photo: Wang Jingyu

What unfolded over the course of the last month is the culmination, so far, of an ever more desperate struggle for Wang. Right now his friends in the U.S. are trying to raise support for him. His girlfriend, in order to stop the Dubai authorities from sending Wang back to China, has traveled to Dubai to try to help any way possible.

Back in China, local police had begun their campaign to capture Wang long before. After his Weibo post in February they quickly mobilized a campaign to try and get him to return ‘voluntarily’, by detaining and harassing his parents, and attacking him on State/Party media, and by reaching out to him directly. When all that failed they went on to pressure Dubai authorities to agree to what would in effect amount to a ‘disguised extradition’: China’s growing long-arm policing on full display. [An investigation into the use of ‘disguised extraditions’ is forthcoming from Safeguard Defenders].

While first held by the immigration police Wang himself has stated in interviews with Deutsche Welle (in English here) and Epoch Times that he was never told why he had been taken and blocked from transiting to the U.S., merely that he had to “wait, wait, wait”. Only after being transferred to the detention centre and after a lawyer was arranged for him by girlfriend, by April 15, did he become aware of the full situation: he was purportedly taken because he had committed the crime of criticising Islam (سب أحد الأديان السماوية المعترف بها, or roughly insulting one of the recognized monotheistic religions).

This reason is listed on the police report on Wang which was opened on April 11, when his arrest was approved, some five days after he was first taken, by public prosecutor Ammar Mohammed Abdullah Al-Marzouki. Police however later started telling Wang that he was being investigated because of threats to national security.

Image: Al Barsha Police Station and detention center

It should be noted that Wang has had no involvement in Dubai or UAE politics or religion ever before, and his past experience with Dubai was merely as a transit hub.

Wang was granted bail by the court on April 26 but through the use of immigration law, police re-detained him immediately, citing the need to deport him. At this stage, Wang was without a legal right to be in Dubai as arrivals need to secure visas on arrival to enter the city-state. However, as his presence in Dubai is entirely based on his detention and as such a permit could easily be arranged by the police to allow him to continue his travel, there are clearly other reasons behind this.

Document: Bail approval, which includes a ban on travel.

Such is rendered more evident by the fact that while the charges against him were dropped on May 20, after the prosecutor recommended it on May 11 due to a lack of evidence, Wang remains in custody at the detention centre.

The prosecutor’s office, when asked for details about his situation on May 23 refused to divulge any information (email: info@dxbpp.gov.ae, phone +971-43346666). The case file with the public prosecutor currently reads as follows:

Document: Case file of Wang Jingyu. The Charge listed at bottom reads insulting one of the recognized monotheistic religions.

What is China after?

On February 19, 2021, Chinese State/Party media admitted that four PLA soldiers had died in the June 2020 clashes with the Indian army. Two days later, on February 21, Wang - who had encountered repeated problems with local police in China in 2018 and 2019, often called in by police for posting online information and views antithetical to the Chinese Communist Party - used his Weibo account to question why it had taken the Chinese government some eight months to admit to these casualties.

According to Chinese party-state television, CCTV, on that same day, at about 7 PM someone reported his Weibo tweet to the local police in Shapingba district of Chongqing city, his hometown. Within two days, on February 23, a notice from the local police was posted on State/Party media about the incident, stating that Wang was under investigation for “Picking quarrels and provoking trouble”. It also noted that Wang was abroad and was being pursued online. He had officially become a fugitive.

Document: Notice from local police on Wang Jingyu as a suspect.

Later on, State/Party media would instead report that he was being sought for violation of the 2018 Law on Protection of Heroes and Martyrs.

Recently seven people were charged with defaming “heroes and martyrs”. One of them, Pan Rui, is, like Wang, living abroad, and is now being sought after by Chinese police for a Weibo post on June 23 last year. Police in Beijing Haidian district that launched the investigation quickly noted that Pan had left China on February 2, 2020, and had been living abroad since then. This did not stop them from pursuing the case, and Pan is now a fugitive. He also happens to be the son of businessman Pan Shiyi, whose work as a real estate mogul is well known to anyone who has spent time in Beijing - being the man behind Soho China and its many iconic buildings around the capital. Pan Rui himself lives in the UK, where he also has a registered business. Pan has not responded to inquiries about the situation of Wang nor about his own situation.

Drama behind the scenes during Wang’s detention

On May 20, when the court approved dropping the charges against him (requested on May 11 by Dubai’s prosecutor), he was twice asked by Dubai police to sign a document in Arabic, without understanding its content. He refused. Police refused to tell him any specifics about what the document contained.

While held in the detention centre, he also received three visits by staff from the Chinese consulate in Dubai and the Chinese embassy in nearby Abu Dhabi. All three visits took place in April, one with two people from the embassy, the other two meetings with two people from the consulate. These visits had one purpose: to get Wang to sign a document, again in Arabic, agreeing to return to China. They told him they wanted Wang on a flight to Guangzhou on May 1.

A similar situation occurred in Thailand in 2015, when dissidents Dong Guangping and Jiang Yefei were asked to sign a document allowing Thai immigration police to release them. After signing it and being released, despite their official status as refugees and in violation of core international law they were handed straight over to Chinese agents and taken back to China where they ended up in prison. Up until now, Wang’s refusal to sign the papers presented by both Chinese diplomatic staff and Dubai police is the only reason Wang has not been sent back to China yet.

Behind the scenes in China

However, Chinese police have been far more active than merely visiting Wang in the detention centre in Dubai and asking Dubai authorities for his return.

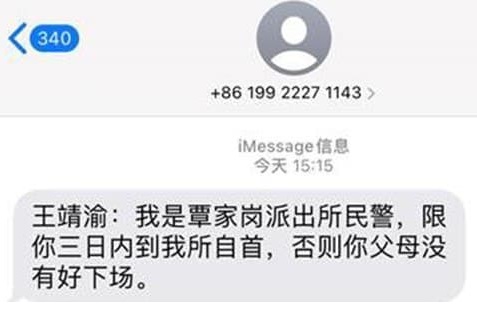

Police first asked Wang directly to return, by sending him a text message reading:

"I am a police officer of Qinjiagang police station. Come to surrender yourself in the station within 3 days, or your parents won’t have a good end."

Image: Screenshot of message from local police to Wang Jingyu

Shortly after his initial Weibo post on February 21, on the very same evening, local police also showed up at his parents’ home in Qinjiagang district of Chongqing, searched the premises, and handcuffed and took both parents to the police station. According to an interview given by Wang on March 1, they were held for five hours. Not satisfied, police escorted them back to their house and had a male policeman sleep with the father, and a female office with the mother, to fully monitor the parents. Following this, police subsequently detained the parents for 12 hours per day on February 22, 23 and 24. Once back home, various government officials continued visiting them at their home, all with the same request: to help force Wang to come back to China.

After these developments, Wang decided to start talking with overseas Chinese language media. Wang revealed that during yet another detention of his parents, on February 25, a police officer beat his mother.

“They forced my parents to call me. Forced them to ask me to go back to China, force me to keep silent and don’t talk to any media. They asked me to post a confession video on Weibo. I rejected all these requests,” Wang said in an interview with Epoch Times on February 27.

February 27 the last time he managed to talk with his parents. After initially being contacted only by local police, Wang stated being contacted by China’s national security police as well.

While all this was happening, his parents were dismissed from their jobs at the China National Petroleum Corporation and Chongqing Water Pump Factory, both State-owned companies.

The combined threats against Wang and against his family back in China is not surprising. Nothing about the behaviour above is out of norm for China, with an ever-growing list of cases and media reports documenting retaliation against family members when the person wanted silenced or returned is outside of China and refuses to submit. These threats - going after family members in China - is a key component of China’s Foxhunt and Skynet campaigns, focused on ‘inducing’ fugitives to return ‘voluntarily’ rather than attempting costly, often difficult and politically damaging, extradition processes. China has been known to send agents overseas to carry out such threats to targets directly - in France, Canada, Australia and Cyprus, for example - but going after family in China and having the family support the police in trying to convince them is far cheaper and commonly used [a major report on the subject is forthcoming from Safeguard Defenders].

The situation becomes dire

At 1 AM on Monday (May 24), local time, Wang called his girlfriend. They spoke for three minutes before the connection was cut.

He managed to tell her that that evening, and the evening before, police visited him for six-hour sessions, from 7 PM to 1 AM, telling him all he needed to do to be set free from the detention centre was to admit to the accused wrongdoing. She also learned that his computer and pad had by now been confiscated, just like his phone earlier during his detention.

His phone was used to access his email account as of the early hours of May 23 (right after that night's interrogation session had ended), and tracking the phone shows it was accessed from the police station. Dubai police had also asked Wang about his girlfriend’s passport number. She rushed to Dubai earlier on during his detention to try to help Wang, and now fears she might become a target of Dubai police as well.

The pressure on Wang is mounting, and at the current state, should he accept any step to be set free from detention, it will likely doom him to deportation back to China, arrest, trial, and imprisonment.

What are ‘disguised extraditions’?

Ideally, forcibly sending someone from one country to another is achieved either via deportation based on immigration law, or through an extradition. Having a person sent back based on immigration law is, if the receiving State cooperates, rather easy. It is usually used for students who work illegally on their visas, those that continue to stay in country after visas expire, or asylum seekers whose claim has been denied.

Extraditions on the other hand are a complicated costly process involving a full judicial review and process, and is an uphill struggle to achieve for a country like China, where torture is rampant, forced confessions stand as the basis for many verdicts and which has no independent judiciary at all.

In fact, as part of China’s Foxhunt and Skynet operations which seeks to return Chinese fugitives, data for 2018 showed that of the 1,335 persons brought back, only 17 returned through extraditions. For the majority, China instead employs various types of induced ‘voluntary returns’, but also a significant number of people returned via deportation.

“I’ve thought about the possibility of being kidnapped back to China by Chinese special agents, but I’m not worried about that. I believe history will remember me and people around the world will remember me.”- Wang in interview.

Many countries want to appease China and will cooperate in using immigration law to return those that should otherwise be subject to an extradition process. In the case of Dubai, the police’s detention of Wang first, and the subsequent action of holding him on (legally speaking) Dubai territory for which he has no visa, will allow them to return Wang to China as they can claim he is an illegal. In this case, Dubai authorities are themselves the direct reason for his supposedly illegal stay, but it allows them to circumvent the extradition process and please China. On the other hand, it also risks making Dubai -whose economic situation is largely tied to its status as a transit point for many international flights - a pariah for many travellers, much like Hong Kong has recently become – a place well known to be unsafe to anyone wanted by the Chinese State.

As a forthcoming investigation by Safeguard Defenders will show that cooperation with Chinese authorities on ‘disguised extraditions’ are rampant also in Western states, but is rarely or never used for obvious political or freedom of speech cases like the case of Wang.

What is currently ongoing in Dubai is a near perfect illustration of a ‘disguised extradition’.

China’s attempt to secure extradition treaties and legitimizing its long-arm policing

Since Xi Jinping came to power and as his ‘anti-corruption’ purge took off under operations Skynet and Foxhunt, China significantly invested in increasing the number of bilateral extradition treaties with countries around the world. This involves in particular also Western democracies in the European Union as they come with the added benefit of granting legitimacy to China’s severely flawed judicial system.

Notwithstanding its ever-increasing repression and mounting concern over its handling of Hong Kong, in October 2020, the Global Times triumphantly stated China has concluded 59 extradition treaties with foreign countries, more than the 54 countries reported in September 2019, with 50 people extradited back to China since 2014 as part of an anti-corruption campaign.

While loudly touting its successes in securing some formal extraditions from several European countries since 2015 in State media, China has not stopped using other means such as organizing unsanctioned police operations on foreign soil to have those wanted return ‘voluntarily’ as a noted 2017 case in France demonstrates.

However, with Western lawmakers increasingly aware of the extra-territorial reach of China’s regime of political terror, bilateral extradition treaties in ten European Member States, generally passed without much public scrutiny over the years, are now coming under fire. Explicit threats made by authorities in both Beijing and Hong Kong and the growing outcry of exiled dissidents on continuous intimidation (direct or through their family members) have no doubt helped. Repeated appeals by the European Parliament, members of national parliaments and human rights defenders may soon lead the majority of those States (with the noted exception of Hungary) to suspend such treaties, as was the case for the majority of EU extradition agreements with Hong Kong last year. As Wang’s case demonstrates, attention will then urgently need to turn to China’s use of other means to obtain the return of those it seeks to silence as Safeguard Defenders’ forthcoming report will highlight.

“… even if I’m in the U.S. or the European Union, they could still extradite me back to China” – as told to Wang by Chongqing police according to an interview.

Time-line (all 2021)

- 19 February: Chinese State/Party media admits to death toll in clash with Indian army in June 2020

- 21 February: Wang posts a Weibo tweet criticising the long delay of announcing death toll

- 21 February: Police search Wang's parents’ house, detains parents

- 22-25 February: Parents repeatedly detained, harassed, and dismissed from their jobs at State-owned companies

- 23 February: A notice from local police is issued that Wang is under investigation

- 27 February: Wang loses contact with his parents

- 5 April: Wang leaves Istanbul bound for New York, transiting in Dubai

- 6 April: Detained by Dubai police

- 11 April: Arrested, case file opened

- 15 April: Wang receives a lawyer

- 19 April: Bail application filed

- 26 April: Bail approved, but police keep Wang in custody claiming deportation is needed

- 11 May: Prosecutor requests that case be dismissed due to lack of evidence

- 20 May: Case is dismissed, but Wang remains in custody based on claimed deportation need

- 24 May: Wang speaks with his girlfriend, call is cut after three minutes. Last communication as of now.

Latest Updates

May 26: Dubai authorities, via the Dubai Media Office, tells Associated Press that Wang had been arrested for “non-payment of hotel bills” and denied he faced any charge for insulting Islam. When shown the official charge sheet, the Dubai Media Office then said Wang had faced the insult charge later, but “hotel payments were settled and charges were dropped and he was let free.”

May 27: Wang Jingyu released from detention, deported back to Istanbul, Turkey, where he arrived from. He says he was handcuffed in the middle of the night and taken to the airplane and sent back to Istanbul. Given one (of two) phones and his passport. His computer, most clothes, etc, remains with Dubai police.

May 27 13.45 GMT+2: Wang has arrived at Istanbul airport.