Why do they add that extra layer of cruelty?

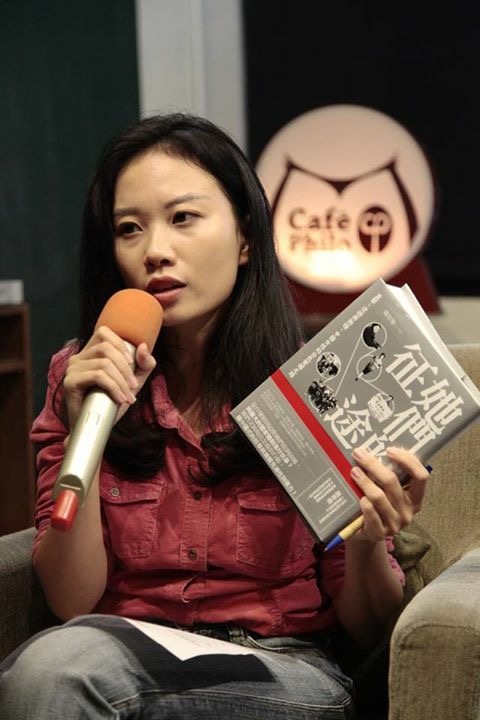

The most chilling aspect of Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) is the fact that it’s allowed under the law, according to Chinese independent journalist and writer Zhao Sile (赵思乐) . “This thing is legal. It’s in the Chinese law; it’s too frightening.” How can you protest something, she asks, when the procedure is legal? “The government can simply answer any criticism with – 'It’s according to our law.'” State-sanctioned enforced disappearances are not new in China, but since 2013, the police have the right to disappear someone, hold them in solitary confinement, and deny them access to family and lawyers for up to six months. “RSDL is more frightening than being in jail. You can’t talk with anyone in RSDL. You’re in a place where people don’t know where you are.” Zhao is talking from Taipei where she recently published a new book about women activists, social movements and political repression in China called 她们的征途 (Her Battles in English). Once someone has disappeared into RSDL they’re lost, and they may be lost forever, she says. “The most terrifying part is [the family] doesn’t know where they are – they can’t send a lawyer to check on them to see if they’ve been tortured.. I think what makes people afraid the most is the not knowing.” They maintain the secrecy, she says, as a cloak to buy time. “If they don’t inform the family, they can keep them for longer.” But this lack of information is unbearably cruel on loved ones.

The most chilling aspect of Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) is the fact that it’s allowed under the law, according to Chinese independent journalist and writer Zhao Sile (赵思乐) . “This thing is legal. It’s in the Chinese law; it’s too frightening.” How can you protest something, she asks, when the procedure is legal? “The government can simply answer any criticism with – 'It’s according to our law.'” State-sanctioned enforced disappearances are not new in China, but since 2013, the police have the right to disappear someone, hold them in solitary confinement, and deny them access to family and lawyers for up to six months. “RSDL is more frightening than being in jail. You can’t talk with anyone in RSDL. You’re in a place where people don’t know where you are.” Zhao is talking from Taipei where she recently published a new book about women activists, social movements and political repression in China called 她们的征途 (Her Battles in English). Once someone has disappeared into RSDL they’re lost, and they may be lost forever, she says. “The most terrifying part is [the family] doesn’t know where they are – they can’t send a lawyer to check on them to see if they’ve been tortured.. I think what makes people afraid the most is the not knowing.” They maintain the secrecy, she says, as a cloak to buy time. “If they don’t inform the family, they can keep them for longer.” But this lack of information is unbearably cruel on loved ones.

“RSDL is more frightening than being in jail. You can’t talk with anyone in RSDL. You’re in a place where people don’t know where you are.”

“Why do they add that extra layer of cruelty by keeping the family in the dark?” she asks. She points to the largely unreported case of Zhao Suli (赵素利), the wife of dissident Qin Yongming, who disappeared without a trace more than three years ago. “No one talks about this case – her children can’t find her – she just disappeared…We’re afraid some accident happened to her. Maybe she just died under RSDL. The police are allowed not to tell families where they are being held so you can just disappear people this way. “They don’t know where to look for her…” Since this interview Zhao Suli has resurfaced – she was allowed a brief visit with her family in early February but is still not free – she is now being held at her own home, according to this report by Radio Free Asia. Zhao Sile has spent many months interviewing the wives of the 709 lawyers, many of whom were victims of RSDL, and for Her Battles she also talked with NGO worker Kou Yanding (寇延丁) who spent 128 days in RSDL (for an extract from Kou Yanding’s own book about her ordeal please see Kou Yanding: You must get our approval for everything). Kou, she said, was still so distressed from her RSDL experience that she found it difficult to talk about it at length, even though several years had passed. Several of Zhao’s friends have also been disappeared, she says sadly, so she has first hand experience of this fear. “One of my friends is now in RSDL. I’m really concerned about him; his name is Zhen Jianghua (甄江华).” Zhen, an online human rights campaigner, was detained on 1 September last year, and is now being held under RSDL on suspicion of inciting state subversion. The latest news in Zhen’s case came in early February, when his lawyer said his application to see Zhen had been denied. Zhao describes how activists, like Zhen before he was detained, have been trying toughen themselves up so they can cope better with the torturous experience of RSDL. “Some young people I know, they’re shutting themselves in some little room, without windows, and they don’t communicate with anyone else for days and keep the light on 24-7 to train themselves for RSDL. They told me that after two or three days they feel like they’re going crazy. It’s hard to imagine how someone can survive these kinds of conditions for six months. It’s terrible. You can hardly imagine how anyone can endure it… Those who’ve been through RSDL and didn’t give up are supermen – like [now jailed activist] Wu Gan (吴淦) and [missing rights lawyer] Wang Quanzhang (王全璋).”

"Some young people I know, they’re shutting themselves in some little room, without windows, and they don’t communicate with anyone else for days and keep the light on 24-7 to train themselves for RSDL."

But however terrible RSDL is, laments Zhao, the world is not paying attention so books like our The People’s Republic of the Disappeared (11 first person-accounts of RSDL), are crucial. “I think it’s a very important work and it’s also a work that is an avant-guard work. It’s refusing to look away from the dark side of China’s human rights crisis when the world is looking away.” The fact that the world is not paying attention is “terrifying,” she says. “[German leader] Angela Merkel is now looking away but many people thought she was one of the few leaders that would not look away, that she would care about human rights. And Norway – they didn’t say anything about [Chinese dissident] Liu Xiaobo (刘晓波) even when he was dying in prison. “What I see is the whole world is looking away, so this book which is trying to uncover the darkest issues in China’s human rights situation is doing respectable and significant work.”