Meet the people in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared

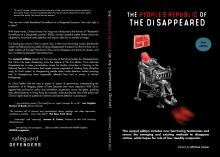

The 11 people who have shared their stories in this book -- with a brand new second edition just out on 1 November -- have done so at considerable risk to themselves, many others have faced reprisals from the Chinese state for speaking out in the past. It has also been painful for them to relive the horrors of their experience. They have made this sacrifice because there is a real need to expose the grave human rights violation of China’s “legalized” system of enforced disappearances, or Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). And to empower the inevitable future victims.

The 11 people who have shared their stories in this book -- with a brand new second edition just out on 1 November -- have done so at considerable risk to themselves, many others have faced reprisals from the Chinese state for speaking out in the past. It has also been painful for them to relive the horrors of their experience. They have made this sacrifice because there is a real need to expose the grave human rights violation of China’s “legalized” system of enforced disappearances, or Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). And to empower the inevitable future victims.

These people are mothers and fathers, lawyers and activists, boyfriends and girlfriends. Real people with real lives who were taken by the Chinese state for their conviction to defend human rights.

The taxi driver turned rights activist

(NEW in 2nd edition)

Zhai Yanmin

Zhai Yanmin (翟岩民) is a human rights activist from Beijing. He ran a few small businesses and drove taxis for a living until, in 2008, his passion for human rights led him to work for grassroots campaigns, in particular helping petitioners. Zhai was one of the first victims of the CCP’s 709 Crackdown Against Lawyers. After his year disappeared in RSDL and detention, he was found guilty of subversion of state power, and given a four year suspended sentence.

Zhai Yanmin (翟岩民) is a human rights activist from Beijing. He ran a few small businesses and drove taxis for a living until, in 2008, his passion for human rights led him to work for grassroots campaigns, in particular helping petitioners. Zhai was one of the first victims of the CCP’s 709 Crackdown Against Lawyers. After his year disappeared in RSDL and detention, he was found guilty of subversion of state power, and given a four year suspended sentence.

The mother and the man who tried to save her son

Wang Yu

Wang Yu (王宇) is one of China’s most respected human rights lawyers. Her most high-profile cases include defending Uighur scholar Ilham Tohti, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2014 as punishment for encouraging ethnic unity. Wang’s courageous rights defense work has won her several international human rights awards and nominations.

Wang Yu (王宇) is one of China’s most respected human rights lawyers. Her most high-profile cases include defending Uighur scholar Ilham Tohti, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2014 as punishment for encouraging ethnic unity. Wang’s courageous rights defense work has won her several international human rights awards and nominations.

Tang Zhishun

Tang Zhishun (唐志顺) was inspired to get involved in civil rights activism after facing (and stopping) the illegal demolition of his own home. Since then, Tang has helped other victims of forced evictions on how to better protect their rights. Police seized Tang and barefoot lawyer Xing Qingxian in Myanmar as they were helping Bao Zhuoxuan, the teenaged son of detained rights lawyer Wang Yu and Bao Longjun, leave the country.

Tang Zhishun (唐志顺) was inspired to get involved in civil rights activism after facing (and stopping) the illegal demolition of his own home. Since then, Tang has helped other victims of forced evictions on how to better protect their rights. Police seized Tang and barefoot lawyer Xing Qingxian in Myanmar as they were helping Bao Zhuoxuan, the teenaged son of detained rights lawyer Wang Yu and Bao Longjun, leave the country.

The professor of law

(NEW in 2nd edition)

Liu Sixin

Liu Sixin (刘四新) is a doctor of law from Hebei province in northern China. After he tried to sue a university official who had sexually harassed his wife, Liu was punished with nearly five years in prison. To protect his family from police harassment arising from his human rights work, Liu divorced his wife in 2013. Working for Fengrui he was caught up in the first wave of arrests of the 709 Crackdown. On 6 August 2016, he was finally released on bail, but is still kept under police surveillance and is unable to leave the country for further study.

Liu Sixin (刘四新) is a doctor of law from Hebei province in northern China. After he tried to sue a university official who had sexually harassed his wife, Liu was punished with nearly five years in prison. To protect his family from police harassment arising from his human rights work, Liu divorced his wife in 2013. Working for Fengrui he was caught up in the first wave of arrests of the 709 Crackdown. On 6 August 2016, he was finally released on bail, but is still kept under police surveillance and is unable to leave the country for further study.

The lawyer who lost his wife to the police

Liu Shihui

Liu Shuhui (刘士辉) is a lawyer and long-time human rights defender. The authorities have barred him from renewing his lawyer’s license since 2010 because of his rights defense work. In 2011, Liu was placed under Residential Surveillance amid calls for a “Jasmine Revolution” in China, when they deported his Vietnam-born wife. He was also disappeared during the 2015 “709 Crackdown.”

Liu Shuhui (刘士辉) is a lawyer and long-time human rights defender. The authorities have barred him from renewing his lawyer’s license since 2010 because of his rights defense work. In 2011, Liu was placed under Residential Surveillance amid calls for a “Jasmine Revolution” in China, when they deported his Vietnam-born wife. He was also disappeared during the 2015 “709 Crackdown.”

The lawyer who defends rights defenders

Chen Zhixiu

Chen Zhixiu (not his real name) (陈志修) is a human rights lawyer who has represented some of China’s most marginalized citizens. Along with investigating human rights violations and acting as legal counsel for rights defenders at risk, he has also researched and taught others in more effective ways to use the law in China.

Chen Zhixiu (not his real name) (陈志修) is a human rights lawyer who has represented some of China’s most marginalized citizens. Along with investigating human rights violations and acting as legal counsel for rights defenders at risk, he has also researched and taught others in more effective ways to use the law in China.

The Swedish rights activist and his girlfriend

Peter Dahlin

Peter Dahlin is a Swedish human rights activist and co-founder of China Action, an NGO that provided legal and financial assistance to rights defenders at risk. Security agents detained Dahlin in early January 2016 and placed him under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location in a secret custom-built facility in the outskirts of Beijing. After being made to appear in a nationally-televised forced confession, Dahlin was deported and banned from re-entering China.

Peter Dahlin is a Swedish human rights activist and co-founder of China Action, an NGO that provided legal and financial assistance to rights defenders at risk. Security agents detained Dahlin in early January 2016 and placed him under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location in a secret custom-built facility in the outskirts of Beijing. After being made to appear in a nationally-televised forced confession, Dahlin was deported and banned from re-entering China.

Pan Jinling

Pan Jinling’s (潘锦玲) only connection with human rights work was her relationship with her boyfriend, Peter Dahlin. Even so, security agents abducted her at night from her home and placed her under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, where she was interrogated and held in solitary confinement for 23 days until the authorities deported her boyfriend.

Pan Jinling’s (潘锦玲) only connection with human rights work was her relationship with her boyfriend, Peter Dahlin. Even so, security agents abducted her at night from her home and placed her under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, where she was interrogated and held in solitary confinement for 23 days until the authorities deported her boyfriend.

The lawyer whose torture under RSDL grabbed headlines around the world

Xie Yang

Xie Yang (谢阳) is a prominent rights defense lawyer; he has represented members of the civil rights group New Citizens’ Movement as well as persecuted Christians and victims of illegal land grabs. In 2015, the authorities targeted Xie in the 709 Crackdown gainst lawyers and activists. Stories of Xie’s horrific torture while under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location hit global headlines in 2016.

Xie Yang (谢阳) is a prominent rights defense lawyer; he has represented members of the civil rights group New Citizens’ Movement as well as persecuted Christians and victims of illegal land grabs. In 2015, the authorities targeted Xie in the 709 Crackdown gainst lawyers and activists. Stories of Xie’s horrific torture while under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location hit global headlines in 2016.

The petitioner who helps others seek justice

Jiang Xiaoyu

Jiang Xiaoyu (not his real name) (江孝宇) got involved with rights work in the early 2000s when he himself was a petitioner. Because he could speak English, he started helping Chinese human rights defenders communicate with foreign journalists and diplomats. Security agents seized Jiang in 2016 and starved and beat him for a weekend in an underground prison in the outskirts of Beijing.

Jiang Xiaoyu (not his real name) (江孝宇) got involved with rights work in the early 2000s when he himself was a petitioner. Because he could speak English, he started helping Chinese human rights defenders communicate with foreign journalists and diplomats. Security agents seized Jiang in 2016 and starved and beat him for a weekend in an underground prison in the outskirts of Beijing.

The human rights lawyer who won’t give up

Sui Muqing

Lawyer Sui Muqing (隋牧青) is well known for his work defending other rights activists, including fellow human rights lawyer Guo Feixiong. The authorities have subjected Sui to repeated attacks, including fines and beatings, because of his work on politically sensitive cases. He was also swept up in the 709 Crackdown in the summer of 2015 and placed under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location. After he was released in 2016, he was able to continue to work as a lawyer for a few years but in 2018 his license was revoked. Now he volunteers his help on human rights cases.

Lawyer Sui Muqing (隋牧青) is well known for his work defending other rights activists, including fellow human rights lawyer Guo Feixiong. The authorities have subjected Sui to repeated attacks, including fines and beatings, because of his work on politically sensitive cases. He was also swept up in the 709 Crackdown in the summer of 2015 and placed under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location. After he was released in 2016, he was able to continue to work as a lawyer for a few years but in 2018 his license was revoked. Now he volunteers his help on human rights cases.