After long break, China airs forced confessions of foreigners

We thought we had seen an end to China’s illegal forced televised confessions of foreigners.

Our campaign, based off our ground-breaking report Scripted and Staged, which revealed how the Chinese police use threats and fear to coerce scripted confessions for television, led to a ban on broadcasts of the international arms of China’s state TV (CGTN and CCTV-4) in several countries, including the UK, Australia and a number of European nations.

As a result, after 2020 China's forced televised confessions of foreigners ceased, except for those of Taiwanese citizens.

But now, it appears they’re back at it again.

On April 3, domestic channel CCTV-13 and the international Chinese-language channel CCTV-4 broadcast the forced confessions of three Filipino expats living in China.

The two young men and one young woman are accused of espionage, something which the Philippine government vehemently denies.

The CCTV-4 broadcast (which includes one of the confessions) was aired internationally, including in Canada, where our long-term regulatory complaint on the use of such forced televised confessions remains pending before the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). The renewed airing of forced confessions, abusive and harmful content, is yet another clear violation of the terms and conditions of CCTV-4’s continued broadcasting license in Canada.

Now, Filipino authorities and TV providers face the same issue, as the illegal forced televised confessions of their compatriots were broadcast on their own soil.

CCTV-4 is broadcast in the Philippines through SKY Cable Corporation. In its public values statement, the pay television and broadband arm of ABS-CBN highlights its commitment to “serving the Filipino”. It claims to uphold a customer service that drives the company “to treat Filipinos as our Kapamilyas (e.g. ‘family’) whose interest is put above all”.

It appears evident the coercive and degrading treatment the three Filipino citizens faced (see below) was far from the treatment one would reserve for family members.

Since these detentions follow the earlier arrests of Chinese nationals in the Philippines on alleged spying charges, many are questioning whether Beijing has engaged in a tit-for-tat response.

If so, this would be yet another example of China’s hostage diplomacy, where foreign citizens are used as pawns in Beijing’s geopolitical spats and its increasingly ambitious posturing on the international stage.

“The arrests can be seen as a retaliation for the series of legitimate arrests of Chinese agents and accomplices by Philippine law enforcement,” Philippine National Security Council, Assistant Director-General Jonathan Malaya said in a statement.

The sequence of events is eerily similar to the fate suffered by Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor between 2018 and 2021. The ‘Two Michaels’ were detained and prosecuted on spying charges in clear retaliation for Canada’s execution of an international arrest warrant against Huawei’s then-Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou.

The phenomenon led to Canada’s ongoing Initiative against arbitrary detention in state-to-state relations.

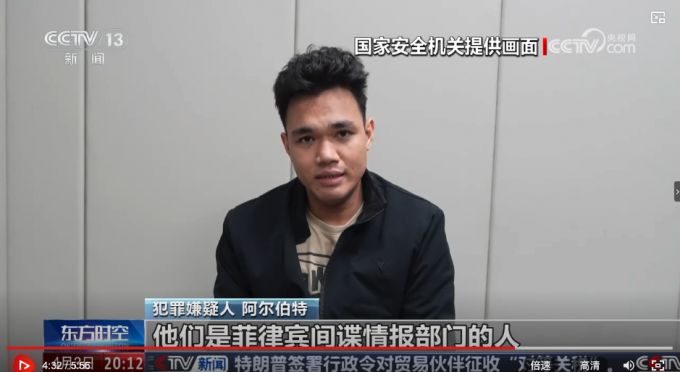

In the confession videos of the Philippine nationals, Chinese names are used for the detainees. Chinese state print media identified them as David Servanez, Albert Endencia and Nathalie Plizardo.

Like many other foreigners who have been victims of China’s hostage diplomacy, the three may now be being held in an incommunicado detention system called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, or RSDL. In RSDL they will be confined separately in suicide-proofed cells without access to sunlight. They are unlikely to be allowed to speak to a lawyer or have anyone else to converse with apart from their interrogators. They could be held in these inhumane conditions for up to six months.

It remains unclear for now whether the Filipino authorities have been allowed consular access to the detained citizens, as stipulated by the two countries' bilateral consular treaty. China has a long tradition of violating such treaties.

Our recent handbook Missing in China was conceived in response to this myriad of violations as a growing number of foreign citizens are arbitrarily detained in the authoritarian country.

The handbook is a combination of the organization’s extensive research in China’s repressive judicial system and the first-hand experiences of former detainees and their families. It offers readers with crucial insights and practical advice to deal with the detention of a loved one in China and aims to help them become the best possible advocates for their family member.

Over the years we have analysed over 100 of these confession videos. This latest one follows exactly the same format.

With one chilling addition.

The detainees are shown being paraded between police officers, cuffed and, in a totally unnecessary move, with black fabric covering their heads, effectively blindfolding them.

The five-minute news package begins with the anchor accusing the three detainees of endangering China’s state security. The program contains no official response from Manila. Their guilt is presented as fact.

Remember, this is long before the three have had any chance to see a lawyer, never mind be tried in a court of law. This is a blatant violation of international human rights standards.

Visually, everything is done to reinforce the idea of their guilt. They are shown:

Locked into tiger chairs.

Handcuffed, their heads bagged and marched in between police officers.

Signing paperwork (presumably confessions). Note all paperwork is in Chinese, even though they are not native Chinese speakers.

The only concession is to call them “suspects” in the lower thirds or titles displaying their name on screen.

Our research into forced TV confessions revealed how Chinese police use threats to force detainees into “performing” the confession – the entire thing is staged for the cameras.

Police write the confession script and the detainee is either made to memorise it or read it with the words off camera (their eye movements usually betray if the latter is the method). They are also dressed for the occasion. They are given clean detainee clothing or told to change into civilian wear (as appears to have happened in this confession video). Many people we interviewed for Scripted and Staged said they normally wore dirty prison outfits in detention or old sweatpants if in RSDL.

The Filipino detainees are in a jailhouse setting: they are shown in a police interrogation room and in a detention centre corridor but in earlier confession videos, Chinese police would often try to hide the coercive aspect by filming confessions in a neutral setting, such as a hotel room or office.

When it comes to the confessions themselves, this video follows the classic forced confession script. This usually includes statements of:

Guilt (the confession)

‘Anti-China’ (“I harmed China’s interests”)

Regret and repentance

Warning (“Don’t be the same as me”)

Gratitude (“Thanking China”)

Requests for mercy

The only element absent for these new forced confessions is a request for mercy.

Servanez, who wears a blue t-shirt and is visibly scared, appears to read from a piece of paper or teleprompter off screen (his eyes keep flicking to the side as he speaks in halting Chinese). He is given the most air time of the three. He confesses to working with a man called Richie Herrara, who he says is from Philippine Intelligence.

“He wanted me to use my stay in China to collect some intelligence for them on China’s military and they would reward me financially every month,” he says. Later in the video, he adds: “The Chinese government gave me a good life, but I did things that harmed China’s national interests. I really regret everything I did.”

He is followed by Albert Endencia who speaks in English. He is dressed in a black jacket and sitting in a tiger chair. He appears very scared.

Endencia says: “I realise I have done things that have endangered China’s state security. The Chinese government and the Chinese people have treated me very well. If there are people who have experienced the same things as I did, I would persuade them to surrender to the relevant Chinese authority.”

Last is Nathalie Plizardo, who wears a pink t-shirt and also speaks in English. Again, she appears to be reading off a script.

She is coerced to say: “I went back to the Philippines in January 2024, and met Richie Herrara national intelligence. I was recruited to work for them. I truly regret what I have done from the bottom of my heart. I shouldn’t work for them.”

The rest of the feature shows police describing their alleged crimes. Unlike the detainees, the police’s identities are obscured with blurred footage and their voices also appear to have been disguised. Like previous confessions videos, few concrete details are given about the crime. For example, the detainees are meant to have taken photos and video of military installations, but there is no explanation of how these three young Filipinos gained access to any security facility.

The video ends with a warning.

“National security authorities remind foreign nationals living and working in China not to engage in espionage or other activities that endanger China's national security at the behest or with the financial support of foreign organisations or individuals.”