Battered and Bruised: a new report on torture in China

The legal definition is still too narrow and only actions undertaken by security officers collecting evidence or extracting confessions can be deemed torture. The issue is compounded by the recent introduction of two new custodial systems, which themselves herald the likely expansion of the practice. Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) and Liuzhi are two similar extrajudicial custodial systems that effectively shield officers from any oversight and put detainees in solitary confinement with no access to legal counsel or family contact for months on end. The report also includes testimony from victims of torture to illustrate the different forms employed in China’s detention centres and prisons and under RSDL.

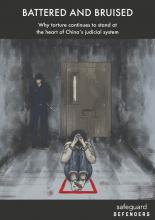

Battered and Bruised: why torture remains at the heart of China's judicial system

Research undertaken by Safeguard Defenders on human rights defender victims of RSDL, which was legalized in 2013, and is being exploited to harass lawyers and activists, reveal widespread and often shocking stories of torture and maltreatment. Liuzhi, a custodial system that replaces (and expands on) the old shuanggui system, was officially launched this March, and is used to extract confessions from Party members and government workers involved in corruption cases.

Why is torture so widespread in China?

It’s been 30 years since China ratified the UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), yet its laws on torture are still not in compliance. In addition, there are other problems with the legal framework. The key issues are:

- The definition of torture is too narrow – for it to be considered torture it must have a direct physical consequence (torturers often conceal this, for example inflicting beatings on the torso or beating so that the body does not bruise).

- It does not include psychological torture

- It does not include torture by anyone except investigating officers

- It does not include torture inflicted in any other circumstances other than collecting evidence or a confession.

- It is extremely difficult for lawyers to collect evidence, police routinely block access to clients and if the client is under an extra-judicial custodial system, such as RSDL or liuzhi than there can be no access at all

The lawyers in our study group concluded that the only way to practically help clients who are victims of torture is to use evidence of that to discard any evidence or confessions extracted through torture at trial.

Types of torture

Torture in China has been well documented by first-hand victim accounts, including most famously by lawyer Gao Zhisheng, but also in our book on RSDL, The People’s Republic of the Disappeared, as well as in research conducted by other human rights organizations. This short report lists some of the most common forms: stress positions – such as being hung up by the wrists, strapped into a Tiger Bench, handcuffed and shackled until limbs swell painfully, electric shocks and asphyxiation. Mental torture (which is largely not criminalized in Chinese law) include sleep deprivation, food and water deprivation, prolonged interrogations and forced medication. Sexual torture, including assault, rape and humiliation, have also been documented. Our RSDL database, which we first announced here, forms one part of the report's evidence. Every respondent has so far described being tortured in RSDL, with sizeable numbers also describing how their family were threatened, how they were forcibly medicated, shackled, and beaten. The dangling chair -- a tall stack of stools on which victims are told to sit for hours on end with their feet unable to touch the floor, and which causes excruciating pain in the legs and spine -- was the most commonly reported torture. None of them had lawyer access in RSDL.