Be careful taking photos in China or you may end up in secret jail

Morrison Lee arrives in Japan in July 2023, the first time he's been allowed to leave China for almost four years. Photo credit: Morrison Lee.

- Taiwanese businessman Morrison Lee spent almost four years locked up or under an exit ban in China

- Lee is one of many overseas victims of China’s secret RSDL jail system

- Detained only because he had postcards deemed sensitive and a few publicly-taken shots of military vehicles on his phone

When Taiwanese businessman Morrison Lee found himself locked up in a hotel room by China’s state security police in 2019, he fantasized about escape.

He knew his situation was hopeless. Even if he managed to get out, China’s fearsome security apparatus, where streetside security cameras could identify him instantly through face recognition software, would reel him back in with ease. But with no one to talk to and nothing to do all day except pace a small area of carpeted room, with three guards watching him, the windows always covered with dark curtains, and the lights on 24 hours, his mind explored ways of breaking free.

“I even thought about using my own blood to write a message for help on a piece of toilet paper and throwing it out of the bathroom window,” he remembers. “But I knew that they would find me and then things would be even more serious.”

Lee was under a type of secret detention system that has been labeled an enforced disappearance and tantamount to torture by the United Nations. Called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL), police can hold victims incommunicado without sunlight, exercise, or access to a lawyer for six months. Well-known RSDL victims include the Canadian Michaels (Kovrig and Spavor), Australian journalist Cheng Lei, and countless Chinese human rights lawyers.

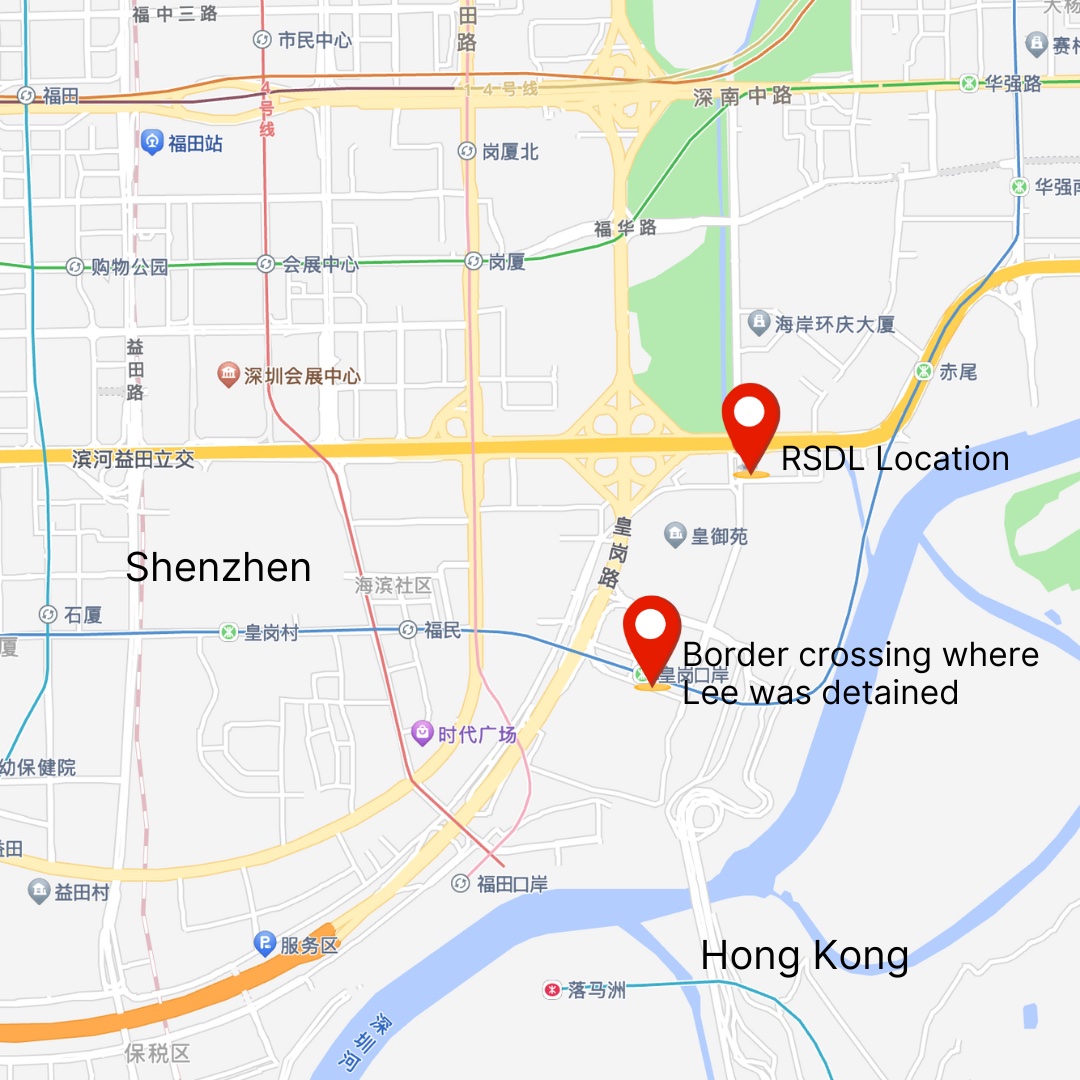

Fateful border crossing

Just a few weeks earlier, in August 2019, Lee had flown from Taiwan to Hong Kong, in order to cross the border into mainland China for a simple two-day business trip. Little did he know that those two days would turn into almost four years.

In his backpack (it was such a short trip he didn’t bother bringing a suitcase) was a digital camera with a lens attachment – “I’m a guy who likes to take photos” – five postcards with a clever graphic design that voiced support for the anti-extradition protests then taking place in Hong Kong – and 200 pink cards that read “Love Peace and Compassion and Communication,“ that Lee said he had made to support Eva Air staff who had gone on strike that summer.

On his last morning in Shenzhen, 20 August, he had breakfast in his hotel, in the city’s central business district. From the window of the hotel’s dining room, he spotted military vehicles in an open area and from his dining table snapped some shots. One of them is pictured below with a vehicle circled. He sent them to a line group (line is a social media platform like WhatsApp, and is very popular in Taiwan), then slipped downstairs to take some more photos from ground level. Lee remembers civilians walking about, no barriers, and no signs warning people not to take photos. He took three more shots and sent one of them too.

After packing his bags, he headed back to the border with Hong Kong to catch his flight home.

“I had crossed that border, I think, more than 25 times before. I had no idea of the danger,” Lee says.

As he attempted to cross into Hong Kong, a border official stopped him and asked him to open his bags. “I thought about this [why I was singled out at the border] for two years,” he says. Lee believes that customs officials had been ordered to be more rigorous in searching the luggage of Taiwanese and Hongkongers crossing the border, perhaps because they would have been seen to be more sympathetic to the protests that were taking place in Hong Kong at the time. His friends who made that same crossing that summer were also subjected to intense luggage checks.

In the end, Lee believes he wasn’t “caught” for anything he had done, he was simply a victim of key performance indicators (KPI) – border guards were told to stop one in every x Hongkonger or Taiwanese travellers and find something they could charge them with. And Lee was easy to spot from his Mainland Travel Permit, issued to Taiwanese who travel to China.

Rummaging through his bags, the border guard became angry when he discovered Lee’s camera filter. “It looks a bit like the gas mask filters that some protesters were using in Hong Kong [to protect them from the tear gas],” says Lee. But after he demonstrated that it was for his camera, the official calmed down.

Then he found the postcards.

“He became very angry and demanded I tell him what they were for,” he remembers. He was escorted off into a room and later several officers arrived. One of the officers said the pink cards were about supporting a colour revolution. Another officer asked why did he have so many cards? Hours went past.

Around 7pm, four officers from Shenzhen National Security arrived and started asking questions about the postcards. After 30 minutes, they marched him to a shuttle bus. He was not handcuffed nor was a black bag placed over his head unlike most of the RSDL cases we have documented. They drove for about 10 minutes to a small hotel where he was taken to a suite on the second floor. That was to be his home for the next 72 days.

Inside RSDL

On the second day, the officers informed him that he was being held in RSDL.

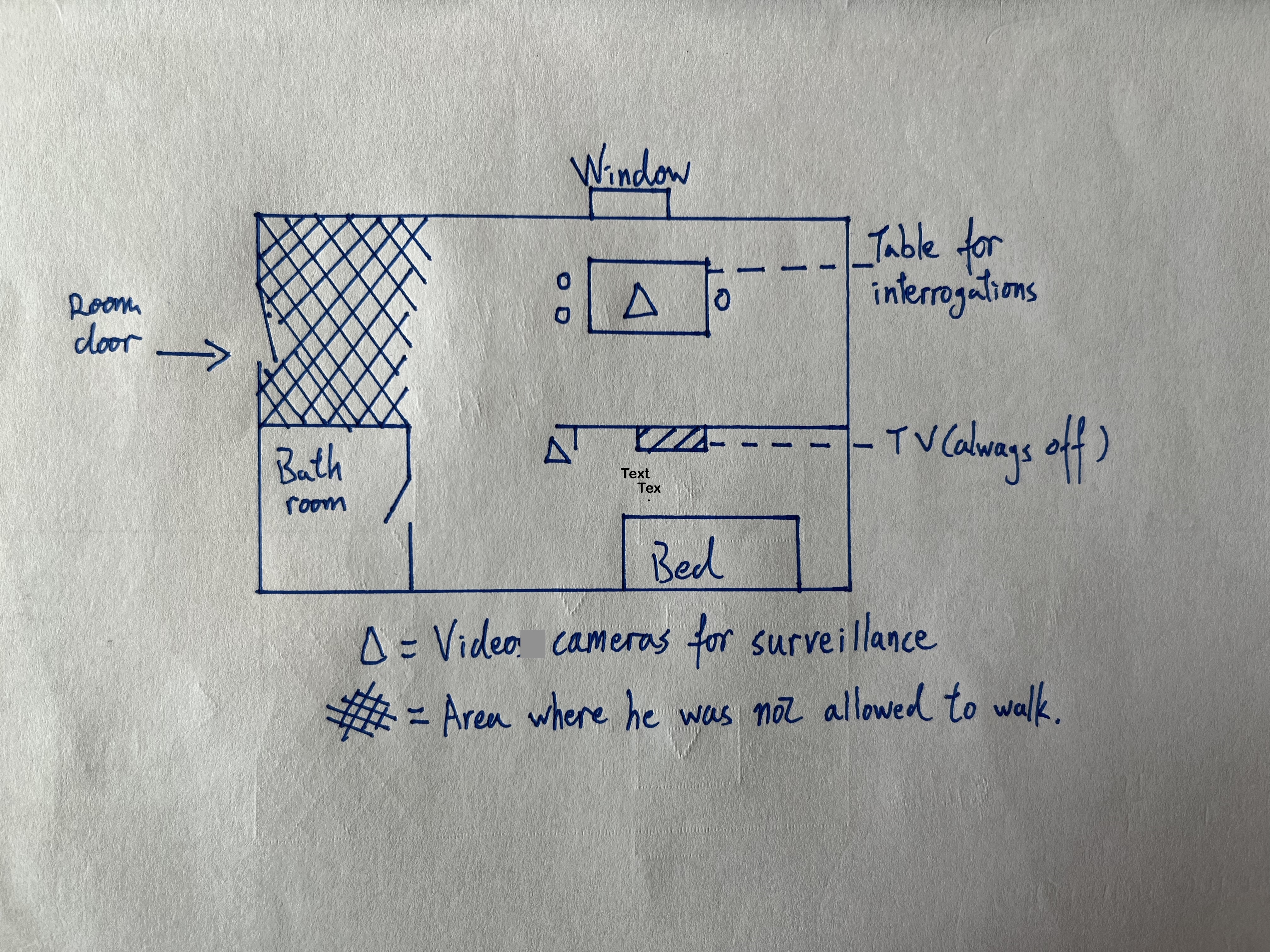

He was being kept in an ordinary hotel room. Unlike other RSDL facilities, it did not have suicide padding, the door did not have a special lock, and there were no surveillance cameras fitted to the ceilings. But video cameras were set up in both the bedroom and in the living area that filmed him 24 hours a day, even while he was asleep. Three guards watched him at all times. He was allowed to walk around the suite freely but was prevented from getting close to the door. Usually, if he went to the bathroom, the guards would follow him.

The living room contained only a table and some chairs. This was where interrogations would take place, says Lee. Under Chinese law, interrogations in RSDL should not take place in the same building as the RSDL.

If there was any kind of sofa, it had been removed. The curtains were always shut and he was not allowed to approach the window nor touch the curtains. The lights were kept on 24 hours a day. In the bedroom, there was a TV, but he was not allowed to switch it on.

During the 72 days of RSDL, Lee had no books, no paper, no pen, no newspapers. He would sometimes try to chat with the guards – ask them where they were from – but usually got no response. Time passed slowly so Lee tried to keep himself busy by cleaning.

“It was very difficult for me, I had nothing to do. So I would clean the rooms - the floor, the table. I would clean everyday. I would also walk around for exercise. To kill the time.”

He was never physically tortured during his RSDL, but state security police threatened him that if he did not confess, he would be locked up forever.

“I was very scared,” he remembers.

Rules in RSDL

Many victims of RSDL talk about the rules they have to obey – usually confined to a small area of the room, required to sleep with their arms above the bedding. In comparison, Lee’s detention was less strict.

“Because I am Taiwanese, I think they treated me better,” he says. As long as he stayed away from the window and the door, he could walk about as much as he pleased. He was allowed to place his arms under the blankets when sleeping, but must not cover his head. Sometimes he was given privacy in the bathroom.

He would wake up at 7am, wash his face and brush his teeth. Breakfast was standard Chinese fare – an egg, soy bean milk and soup dumplings. “It was decent food,” he remembers. Lunch was at noon. They brought him a variety of food, including pizza, coke and soups. Dinner at 5.30 to 6pm. He always ate alone.

Two years later, after Lee was freed but unable to leave China because of a two-year exit ban, he went back to the location. “It was no longer a hotel, it had become some kind of association building,” he says.

Interrogations

Over the course of the 72 days, he was interrogated more than 100 times. Each time for one or two hours.

“I kept count,” Lee says.

Some days he would be interrogated two or three times, other days he would be left alone. In the beginning they kept asking about the postcards. They also grilled him about his past – where he went to school – even elementary school -- his MBA which he studied for in New York, any NGO work he had done. “They wanted so much detail.”

Later, when he was in detention and able to see a lawyer, he learned that the police were looking to charge him with splittism and then incitement to subversion of the state, both based on the postcards. But the prosecutors rejected both because of insufficient evidence. Finally, the police switched tactics, and charged him with “spying and illegally providing state secrets to foreign entities” based on the photos of the military vehicles – freely visible to anyone in that area – that they found on his phone and saw that he had sent by line to friends in Taiwan. Prosecutors gave the go ahead and on 31 October Lee was moved out of RSDL and to Huadu District Detention Centre, (花都区看守所), in Guangzhou, several hours drive west of Shenzhen.

Back in Taiwan

When Lee went missing in August, back in Taiwan his family first filed a missing persons report with local police in the northern city of Hsinchu. The officers could only tell them that Lee had left Taiwan and hadn’t returned.

Then, through some Taiwanese contacts, they phoned Shenzhen police. After they sent the Chinese officers a photo of Lee, the Shenzhen police took just minutes to use public facial recognition camera footage and a database that had his ID number to confirm that he had been in Shenzhen. The officers didn’t know or didn’t tell them that Lee had been detained though, and Lee’s family contacts told them to keep quiet about his case for fear of making things worse.

But at the end of August, media reported Lee missing and he believes from that day, his treatment in RSDL (day nine) began to improve based on the fact that his case had been made public.

It wasn’t until 11 September, three weeks after he was taken, that China confirmed he had been detained. A month later, on 11 October, when Lee was still locked up in that hotel room, Chinese state TV broadcast a forced confession video of Lee (to be covered in part two on this website).

Detention, Prison and Exit Ban

Lee would spend the next year and five months in detention. The first time since he was disappeared on 20 August 2019 that he was allowed to see a lawyer was in January 2020.

"My family told me that they had contacted more than 10 lawyers but none of them wanted to take on my case.” They finally found one willing.

Lee was lucky, he was allowed to hire a lawyer of his choice. Many human rights defenders in China are prevented from hiring their own lawyer, instead having to take a state-appointed attorney.

However, the lawyer did not have much power to help him. “I felt that the only use of that lawyer was to help me communicate with my family, he did not defend me at all. He just asked me to plead guilty... he said that way I would get a shorter sentence; it’s the only way he could help me.”

Initially, Lee wanted to profess his innocence, but in the end he went along with his lawyer’s advice. China has an almost 100% guilty rate.

The lawyer, however, did pass messages between Lee and his family members. He was not allowed to meet with his family or talk to them, and no Taiwanese official ever visited him in RSDL, detention or prison. His hearing was held on 15 June 2020, with sentencing not until the next year on 15 January. He was given one year and 10 months.

For Lee, the period between the court hearing and his sentencing was the most difficult period of his incarceration in China. “I had no idea how many years they would sentence me to, that was very painful,” he remembers.

After sentencing, he requested to be transferred to prison where he enjoyed better conditions and where he could meet other Chinese prisoners. Because of time served, he was released around four or five months later.

However, one month before he was freed, he got a shock.

“An officer told me I had to serve an additional two years Deprivation of Political Rights, which included an exit ban. I was very shocked. Nobody, including my lawyer, had warned me about this.”

For more on the growing number of Exit Bans in China please read our latest report,Trapped.

After his release he travelled to Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing to ask Exit-Entry Administration officers if he was banned. They told him they had no information on his case and suggested he try to leave. So he booked a flight in Shanghai but at the last moment he was prevented from boarding.

Three days before the two years were up, police sent him a text message to tell him he would be able to leave once the sentence was over.

On his flight out on 24 July 2023, almost four years since he had gone on that fateful business trip, Lee wept. “It was four years of tension coming out,” he remembers.