CCP crushing Hong Kong civil society

This guest post by writer and activist Kong Tsung-gan (江松澗) is an updated, edited and expanded version of an article that first appeared on Kong’s Medium blog titled: ‘The Chinese Communist Party is decimating Hong Kong civil society’. See the original here.

The year 2021 witnessed the decimation of civil society in Hong Kong due to repression by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Such a phenomenon in today’s world is quite uncommon: a relatively well-developed liberal society forced back to the political stone age. That is indeed what is happening to Hong Kong before the eyes of the world.

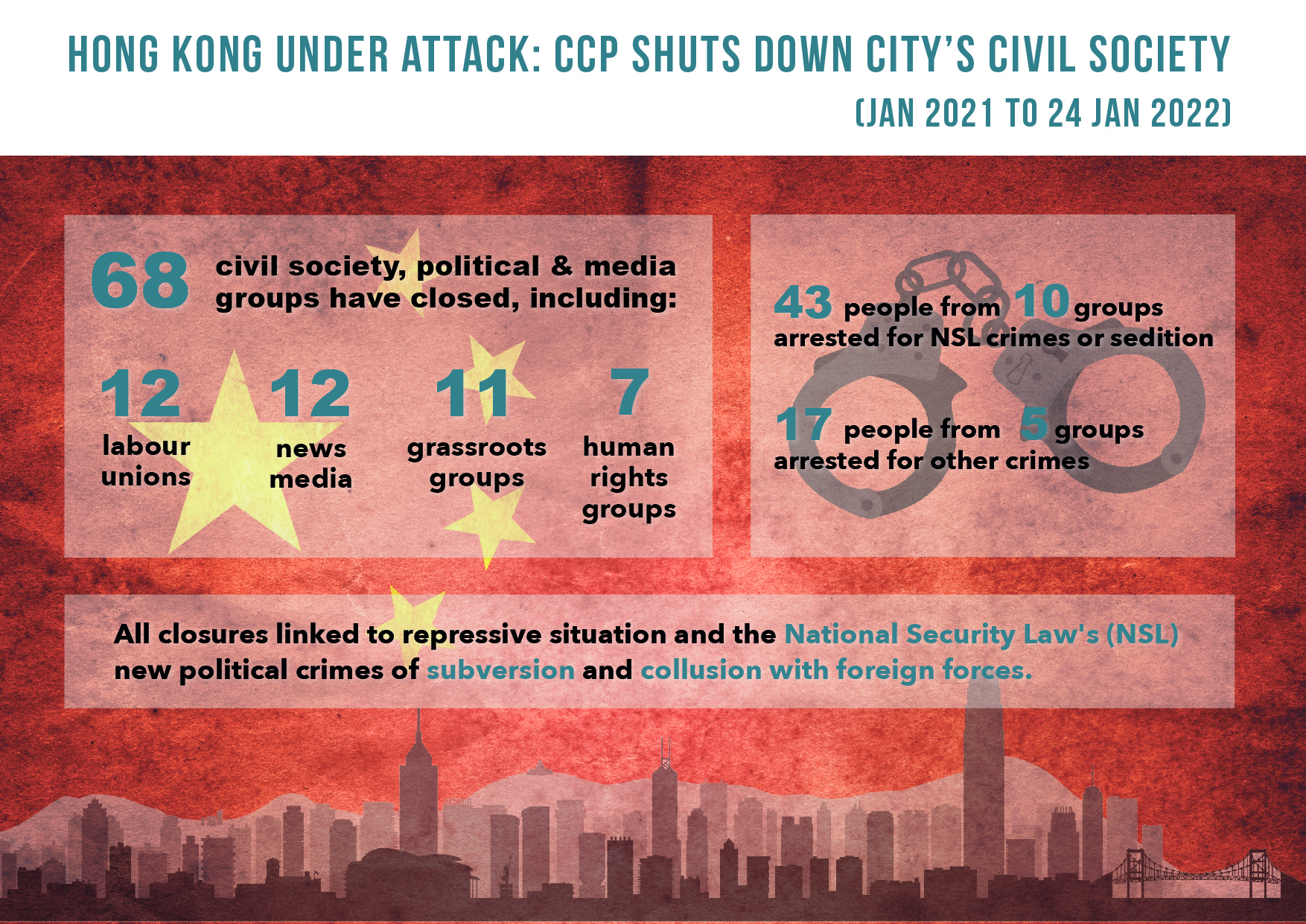

As of 24 January 2022, some 68 civil society organizations have closed due to state repression since the start of 2021.

When they announced they were disbanding, all alluded in one way or another to the deteriorating political situation in Hong Kong as the reason for closing.

What groups have closed down?

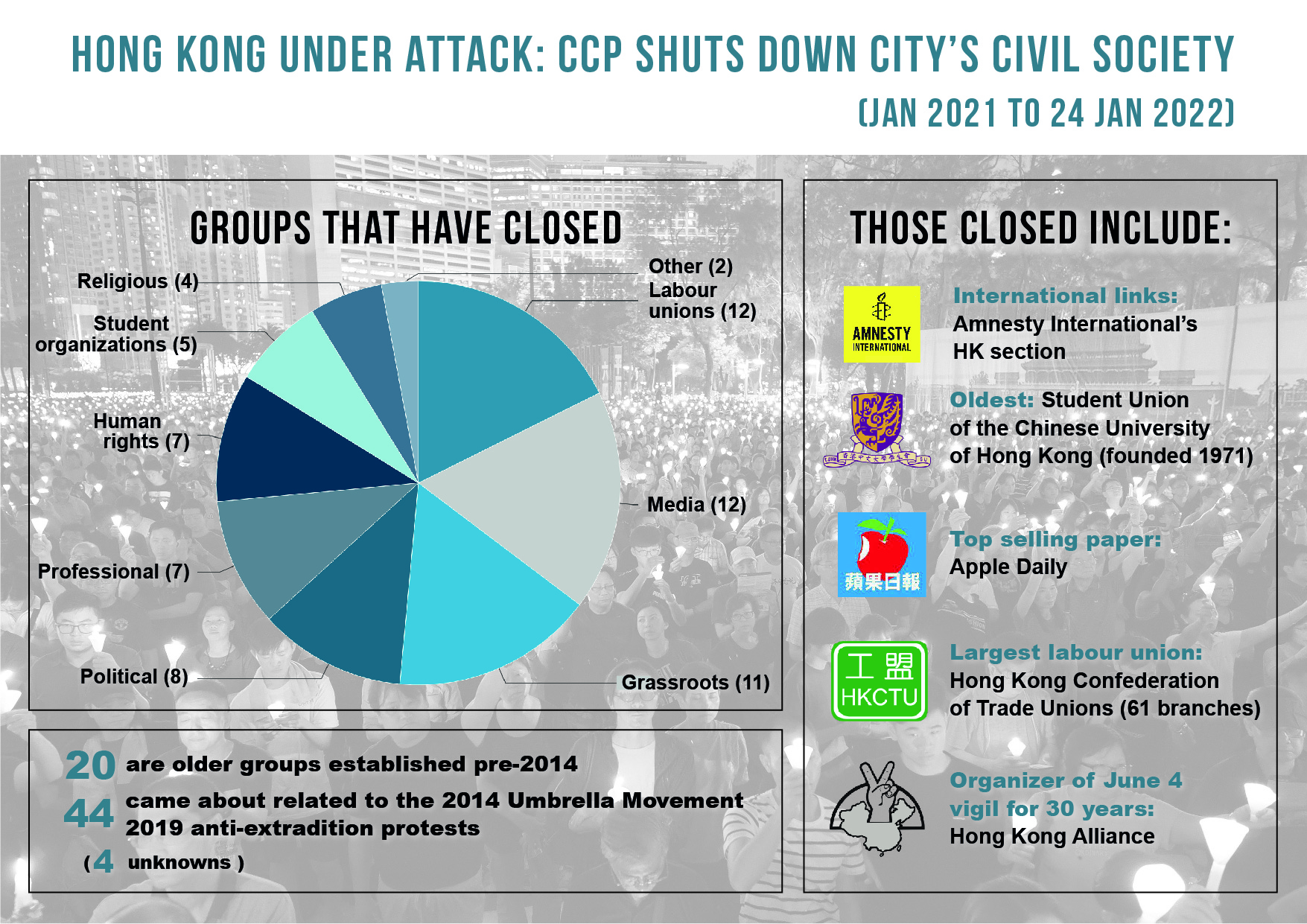

Old and new, big and small, famous and obscure, they were of many diverse types: 12 labor unions*, 12 media organizations, 11 grassroots groups, eight political groups, seven professional groups, seven human rights and humanitarian organizations, five student organizations, four religious groups, and two others (as of 24 January 2022).

They include:

- some of the oldest civil society organizations in Hong Kong: such as the Student Union of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, founded in 1971, and Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union, founded in 1973;

- Hong Kong’s biggest daily newspaper, Apple Daily;

- Its biggest pro-democracy labour group, Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions, with 61 member unions representing 160,000 workers;

- The main pro-democracy protest coalition, Civil Human Rights Front;

- The group that organized the June 4 candlelight vigil for thirty years, Hong Kong Alliance;

- And the largest group helping arrested, prosecuted and injured protesters, 612 Humanitarian Relief Fund, which raised an astounding HK$236,383,746 in crowdfunded donations from ordinary people.

Forty-four of the 68 groups were quite recent in origin, having emerged out of the two biggest movements in Hong Kong in recent years, the Umbrella Movement of 2014 and the 2019 protests. Only 20 of the 68 were founded prior to 2014. (The dates of founding of four of the groups are unknown.)

Many other civil society organizations that have not formally disbanded have become moribund. In the oppressive political climate, it is difficult for many organizations to retain old members or recruit new ones.

Why have they closed down?

The attacks on civil society organizations are part of a larger crackdown that encompasses virtually every sector of Hong Kong society, that indeed is aimed at forcibly pacifying the Hong Kong people themselves.

Some of the more prominent elements of the crackdown include:

- mass arrests of protesters and political leaders;

- attacks on the media and rule of law;

- a comprehensive “reform” of what was even before only a semi-democratic political system to exclude anyone of whom the CCP does not approve;

- enforcement of political obedience at schools and universities as well as the civil service through loyalty oaths, political education campaigns, and other forms of intimidation;

- and a ban on all protests since 28 March 2020 on the public health pretext of coronavirus prevention.

In addition to the above, the so-called National Security Law (NSL) was imposed on Hong Kong directly by the CCP on 30 June, 2020. It designates the new political crimes of “secession”, “subversion”, “collusion with foreign forces” and “terrorism”. As of December 29, 2021, 185 people had been arrested and 111 people and six organizations prosecuted for the NSL crimes of subversion, secession, collusion with foreign forces and terrorism as well as the non-NSL but related crime of sedition, which is investigated by the National Security Department of the Hong Kong police and adjudicated by designated NSL judges.

Some of the closed organizations and their members are among those charged under the NSL, but more generally, the NSL has cast a pall over Hong Kong civil society as it is employed in such broad and arbitrary ways so as to make people uncertain exactly what may be in transgression of the law. Apart from the criminal charges cited above, there are no particular clauses of the NSL that have been invoked to shut down civil society organizations; rather, civil society organizations find themselves unable to operate under the conditions which the law is responsible for creating.

How have they been closed down?

The regime has employed a variety of means to close them down. It forcibly closed only one organization, Hong Kong Alliance, by removing it from the Companies Registry, though the Alliance had already announced that it was closing. In the cases of Apple Daily and Stand News, the police froze the companies’ assets, making it impossible for them to continue to operate, this in spite of the fact that neither companies nor their employees were convicted of any crimes associated with the investigations nor had any evidence been presented in court linking the crimes of which they were accused with the funds that were frozen.

Most organizations took the decision to close themselves, noting the difficulties of operating in the current political environment. Many feared that if they didn’t close, their employees or members would be arrested. In the wake of the arrests of seven people associated with Stand News on “sedition” charges in late December 2021, seven other media companies closed saying it had become impossible to operate in a situation in which no one could judge what the bounds of the acceptable had become.

Some other organizations have decided to leave Hong Kong, closing their offices in the city, including the Chinese-language news website Initium and Amnesty International (AI). AI specifically cited the NSL as the reason for its move. It closed two offices, an Asia regional office under its International Secretariat based in London and the AI Hong Kong Section, which is properly a local organization and is therefore listed above. The New York Times announced weeks after the NSL came into effect that it was moving its digital news operations from Hong Kong to Seoul, South Korea, citing difficulties in procuring work visas for its journalists that were previously easy to come by.

Impact of the NSL on civil society organizations

Forty-three members of ten of the disbanded groups have been arrested by the National Security Department (the Hong Kong police unit charged with enforcing the so-called NSL) and/or prosecuted under the so-called NSL or sedition, including:

- Five members of the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists for “sedition” for publishing three allegorical books for children about sheep;

- Seven members of Hong Kong Alliance — three for “inciting subversion” though they did no more than say the same thing they have said for decades, and five for refusing to comply with police demands for information (one faces both charges);

- 11 executives of Apple Daily for “colluding with foreign forces”;

- And six current and former staff members of Stand News including Cantopop star Denise Ho for “sedition”;

In addition, five groups have themselves been charged as entities under the NSL, Hong Kong Alliance, Best Pencil (Stand News’ parent company), and three Apple Daily entities.

On top of that, 17 members of five disbanded groups are facing trials for other crimes besides NSL crimes and sedition, including 11 from Hong Kong Alliance and one from Civil Human Rights Front.

What’s next?

The CCP intends to put an end to independent Hong Kong civil society as we have known it. It will continue to take whatever steps it deems necessary in order to achieve this objective. This leaves civil society organizations that still exist with basically two options: comply with the unwritten rules of the new era or close down. Either way, the regime’s goal is achieved. Because of this, the short-term outlook for Hong Kong civil society is exceedingly grim.

In terms of governance, the CCP’s goal is that Hong Kong resembles any other Chinese city as much as possible. It is “harmonizing” formerly quite independently-operating public institutions such as Radio Television Hong Kong, the public universities, and the judiciary. In this sense, the crackdown on civil society is just one piece in the bigger puzzle of bringing the whole society into line with CCP diktat.

As is the case with totalitarian regimes, the CCP also wishes to “reform” the hearts and minds of Hong Kong people. Up to now, there is little to no indication that this has begun to take place. Public opinion in Hong Kong has become difficult if not impossible to accurately gauge since polling organizations are no longer able to operate freely, but it appears to be the case that the opinions of Hong Kong people, the majority of whom want to live in a free, democratic society, have not changed. In this sense, what the CCP has done is to drive an entire population underground: they can no longer speak freely but that hasn’t changed the way they think and feel about their home and its political situation. Ever more, Hong Kong feels like an occupied city, with a foreign power imposing its will by force.

How long this situation can continue is hard to say. The CCP hopes that, as in China, its propaganda in education and the media, with ever fewer opposing views expressed, will over time mold Hong Kong people into if not loyal, then at least compliant subjects. In the meantime, it will continue to bring more people from China to Hong Kong via the One-Way Permit Scheme for immigration and other measures, and most likely a steady stream of Hong Kong citizens will emigrate, as tens of thousands have already done. This will change the demographic composition of Hong Kong and increase the size of its diaspora, which will bear an ever-greater burden to carry on the resistance. Already, many new civil society organizations have sprung up in the diaspora.

The resolution of this on-going, chronic political crisis will depend on many external factors, in particular, the state of CCP governance in China and the geopolitical situation. Will democracy make a comeback internationally? Will a CCP-ruled China become more isolated? Hong Kong people hope they can hold out until the stars align in their favour.

*(The Labour Department lists 63 trade unions as having de-registered in 2021. In most of those cases, the reason for closure is unclear and therefore only the 12 that closed explicitly due to the political situation are counted here.)

Kong Tsung-gan is a Hong Kong writer and activist. He has written three books on the Hong Kong freedom struggle: Umbrella: A Political Tale from Hong Kong about the Umbrella Movement; As long as there is resistance, there is hope: Essays on the Hong Kong freedom struggle in the post-Umbrella Movement era, 2014-2018; and Liberate Hong Kong about the 2019 protests. He monitors arrests and prosecutions of Hong Kong protesters and political leaders as well as closures of civil society organizations and the number of political prisoners in Hong Kong. His work can be found here.

(For the purposes of simplicity, this article uses civil society as an umbrella term to include pro-democracy linked professional, political and commercial bodies, such as media titles and political parties, as well as the more traditional non-profit groups).