China’s Pincer move against regulated detentions

On 26 April Safeguard Defenders filed updated data to relevant UN organs on China’s use of its dual systems for enforced disappearances and arbitrary detention: RSDL and Liuzhi. The data presented therein - the most up to date and comprehensive set of data anywhere - is the basis for this article.

This extended post is best read on computer, not mobile. Download as PDF here:

***

Unbeknown to most, since Xi Jinping assumed power, China started implementing two regulated and “legalized” systems for secret detention and enforced disappearances: 1) RSDL, aimed at rights defenders, civil society, and “regular criminals”; and 2) Liuzhi, aimed at Chinese Communist Party members, State functionaries, but also against those working within academia, State-Owned Enterprises, State-media, local contractors, or anyone related to any of the above.

RSDL – short for Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location - came into effect in 2013, while Liuzhi – “retention in custody” – has been adopted in 2018. While both systems have predecessors, their current functioning is very much a product of Xi Jinping’s China. They are but two of many developments that have severely undermined regulated detention and criminal justice procedure since 2013, and represent key loopholes against legal safeguards otherwise available for those targeted with detention, arrest and prosecution.

RSDL – short for Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location - came into effect in 2013, while Liuzhi – “retention in custody” – has been adopted in 2018. While both systems have predecessors, their current functioning is very much a product of Xi Jinping’s China. They are but two of many developments that have severely undermined regulated detention and criminal justice procedure since 2013, and represent key loopholes against legal safeguards otherwise available for those targeted with detention, arrest and prosecution.

To ease the readers’ insight into these systems, Safeguard Defenders is releasing two simple one-page factsheets on RSDL (also at bottom) and Liuzhi (also at bottom), and available in our Publications section.

Following submissions by Safeguard Defenders and partner NGO’s, United Nations Independent Experts have repeatedly condemned the use of RSDL and Liuzhi as tantamount to enforced disappearances and torture. Already in 2015, the UN Committee Against Torture expressly called on the Chinese authorities to repeal the system of RSDL as a matter of urgency. China has since failed to submit its periodic report to the Committee, due in December 2019.

On April 26th, we presented an update submission on the extent of use of the systems to the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture.

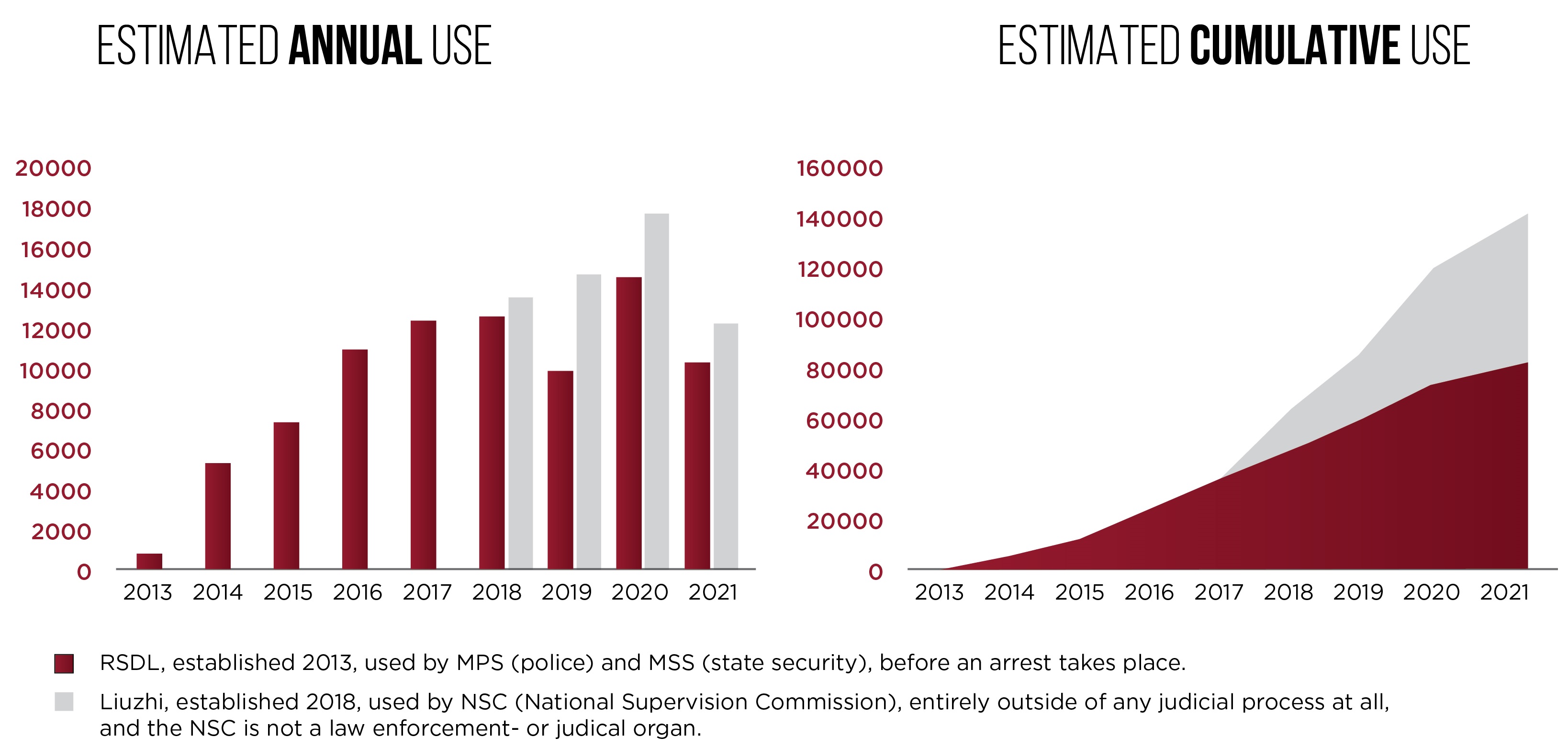

As that data shows, the use of disappearances and arbitrary detention in China is significantly growing and is neutering almost all sectors of potential dissent from the government’s hard-line, both within civil society and the government, academia and the Party.

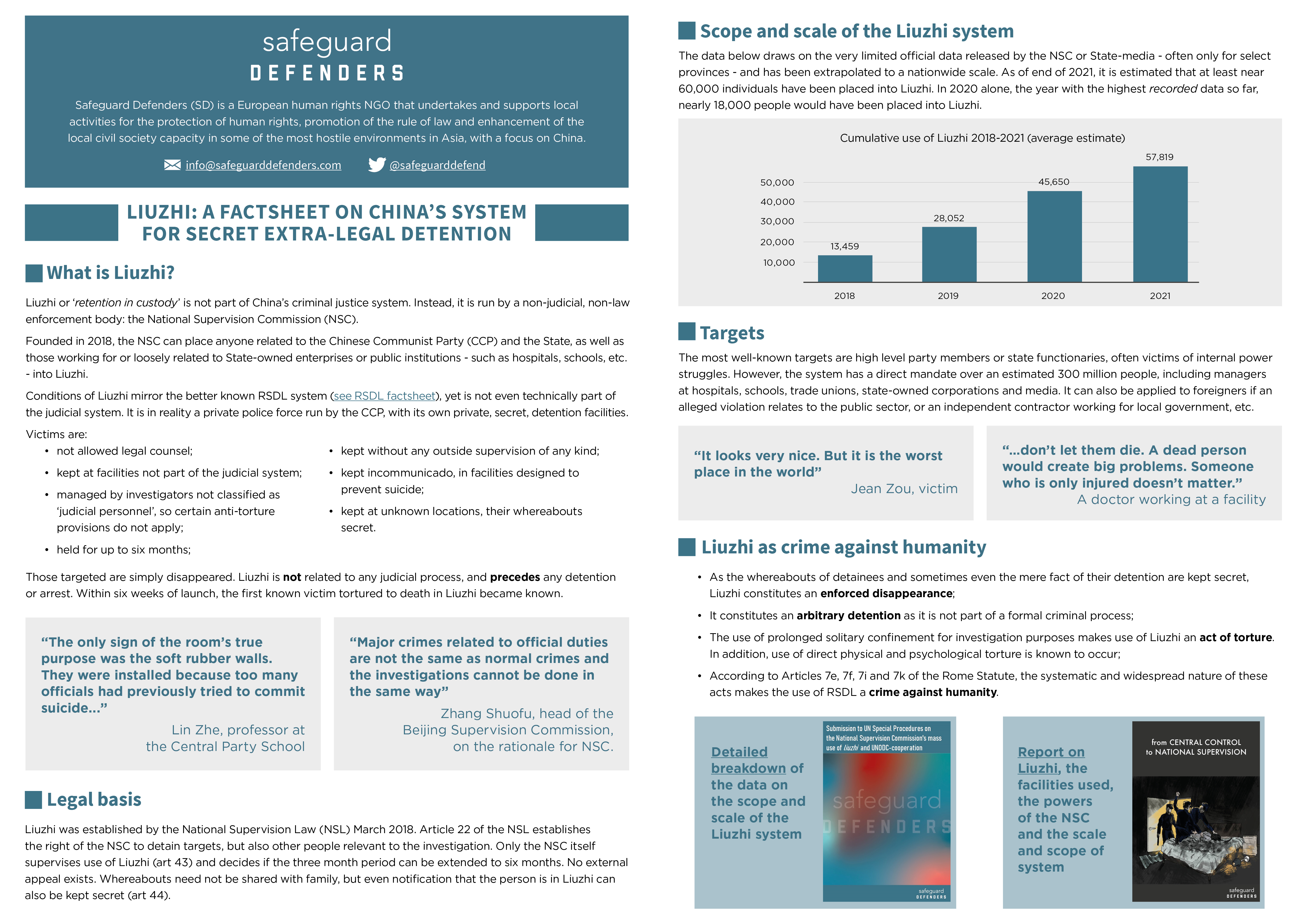

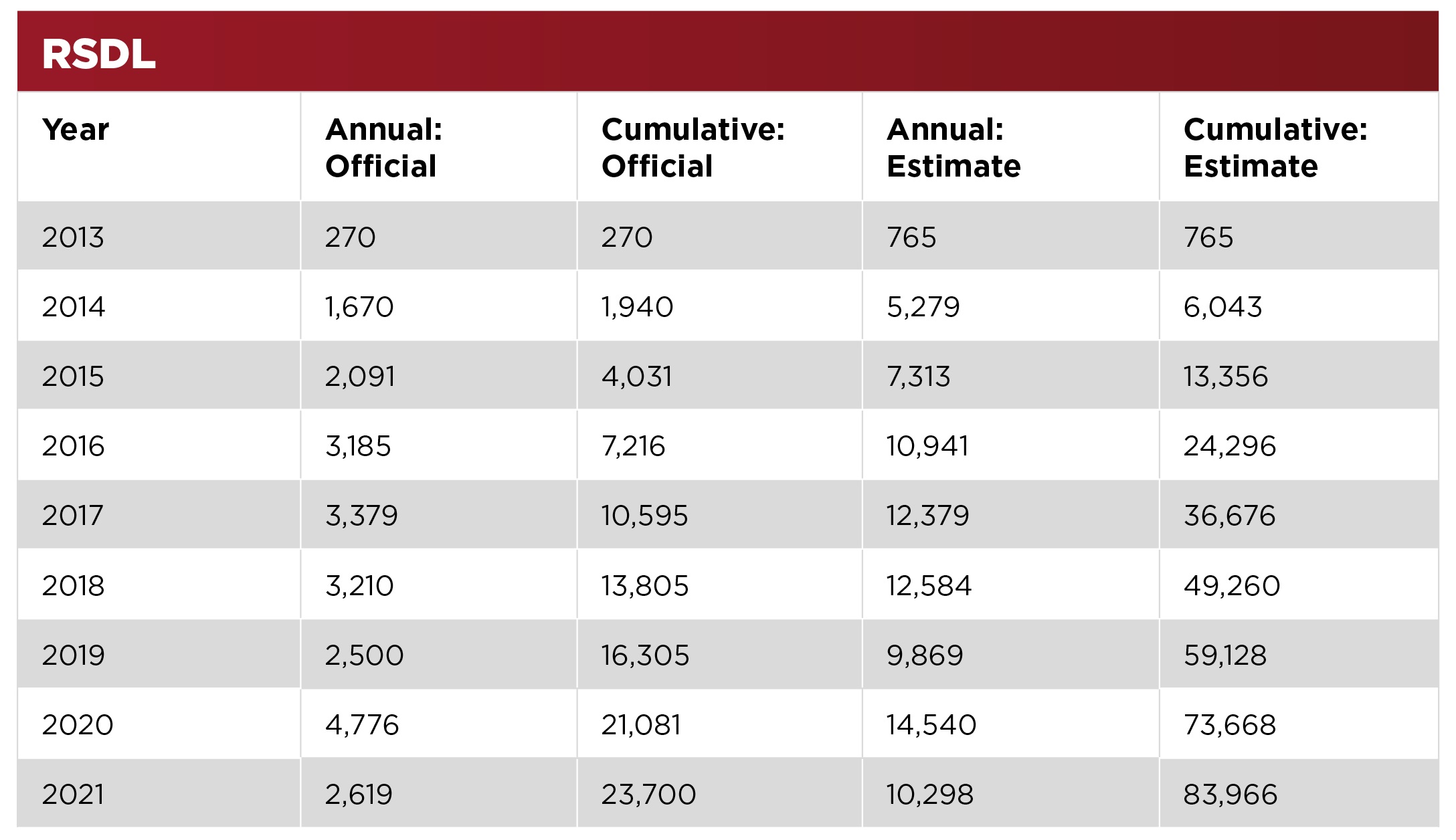

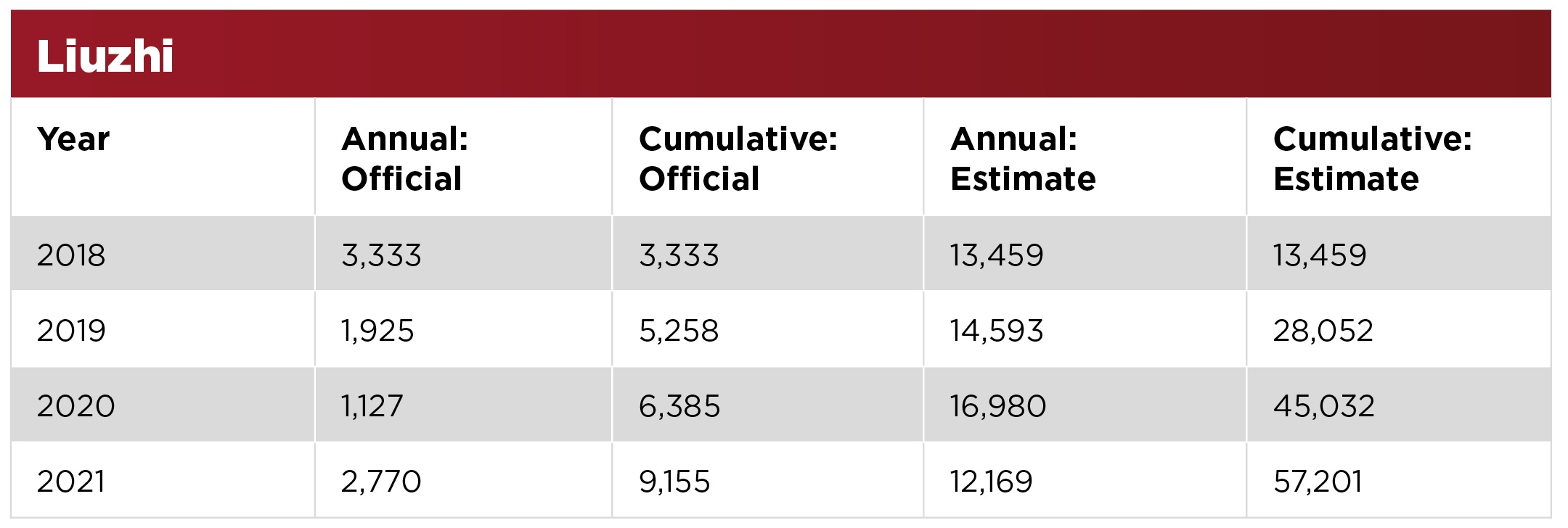

Data on the scope of RSDL is drawn from China’s Judgment Online, a database on verdicts run by the Supreme Court, while data estimates on Liuzhi comes from public statements by the CCDI (the Party-organ that runs Liuzhi) as well as their work reports to the National People’s Congress and Party/State media reports.

For anyone working in government-related environments in China, the sheer mention of Liuzhi is bound to send shivers down their spine. The same goes for any lawyer, journalist or civil society worker at the mention of RSDL.

The horrors inside the Liuzhi system have been exposed in the extensive Human Rights Watch report Special Measures, back when the system was used exclusively on Party members and called “Shuanggui”. The functioning of the re-editioned Liuzhi system has been analysed in Safeguard Defenders’ brief From Central Control to National Supervision and in exhaustive submissions to the UN.

Treatment inside RSDL has been extensively covered by Safeguard Defenders in the acclaimed publication The People’s Republic of the Disappeared, in the graphic report Locked Up, and in data-centered analysis of its scale and scope in Rampant Repression as well as various UN submissions.

A widespread and systematic practice

With both systems operating simultaneously since 2018, modest estimates indicate that at the very least 104,492 people have disappeared into the systems (47,291 into RSDL; 57,201 into Liuzhi). These include a number of high profile targets such as actress Fan Bingbing, Supreme Court judge Wang Linqing, former Chairman of Interpol Meng Hongwei (and probably mogul Jack Ma), as well as numerous foreign citizens, including Canadian diplomat Michael Kovrig. If we add data on RSDL use between 2013 and 2017, the number rises to 141,167.

At the basis of these estimates, one dataset is of particular interest: the minimum number of acknowledged cases. These are numbers provided directly by the Chinese government (or Party) and cannot therefore not be disputed by the government (or Party).

For RSDL - drawing from the Supreme Court website on verdicts for criminal trials at first trial – up to February 18, 2022, that number is 23,700 (verdicts, nor persons) for 2013 to 2021; or 13,105 for 2018 to 2021 only.

For Liuzhi, despite the extremely limited amount of public data available (published numbers exist only for 8/33, 3/33, and 3/33 provinces or regions for 2018 to 2020 respectively, plus CCDI data of 5,006 Liuzhi placements for investigation into the sole accusation of “bribery” for 2021), that number is 11,391.

These numbers place the combined acknowledged use of RSDL and Liuzhi at 35,091 since 2013.

However, occasionally some additional data are released, such as the CCDI’s number of Liuzhi placements as part of a specific campaign targeting law enforcement officials (全国政法队伍教育整顿) citing 1,760 cases of Liuzhi between March and June 2021, and 2,875 between February 27 and end of July 2021. If these two data points are extrapolated to the full year, it would indicate 5,280 to 6,900 people were placed into Liuzhi in 2021 as part of this campaign alone.

While some cases in this dataset might overlap with the provincial or “bribery” campaign data, there is no way to account for them in the officially acknowledged numbers, but it does provide a clear indication that the estimated number for 2021 is far too low, and that likely there has been a continued growth compared to 2020.

Safeguard Defenders has consistently used and extrapolated the little publicly available data provided by Chinese authorities to provide a more likely conservative estimate on the scope of use of the systems:

The full methodology for the RSDL data can be found in Rampant Repression, while the methodology for the estimates on Liuzhi can be found in our latest evidence submission here.

Fog of war and crimes against humanity

Safeguard Defenders presents these data and estimates both for the purpose of informing UN Experts and governments on their continued and expanding use, and because the “fog of war” is increasing.

Year by year, the CCDI has released less useful data on its use of Liuzhi, and if this trend continues it will be harder and harder to make realistic estimates on its use in the future. More worrying - and another trend that is damaging China’s criminal justice system in and of itself - is the systematic removal of information from the China Judgments Online database. One ChinaFile investigation estimated that some 11 million verdict were actively removed during three months in early 2021 alone.

Safeguard Defenders’ own regular searches in the database - for RSDL-monitoring, but also on other issues - has also witnessed a reduction in verdicts available, with older ones being deleted, and new ones likely being uploaded on a reduced scale.

Between February 2021 and February 2022, some 6.5% of verdicts mentioning RSDL have disappeared for the years 2013 to 2019. It is very likely the data that is available will soon be so reduced that realistic estimates will become ever more difficult to make.

The “fog of war” is set to increase on both these issues, and the latest data provided to UN Experts might be the best and most realistic data we can expect to get.

In any case, the data shows beyond any doubt that the use of RSDL and Liuzhi are both widespread and systematic, thus constituting a crime against humanity under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court for they are enforced disappearances and acts of torture according to international law. Furthermore, Liuzhi also constitutes arbitrary detentions carried out entirely by an organ of a political party rather than a law enforcement agency.

Factsheet on RSDL

Factsheet on NSC and Liuzhi