China’s exit bans are now so extreme that one man escaped on a jet ski

In just the short space of four months since we published our report Trapped: China’s Expanding Use of Exit Bans, travel bans in China have continued in force, prompting daring escapes and even preventing teenagers and octogenarians from leaving the country. Here are just some examples:

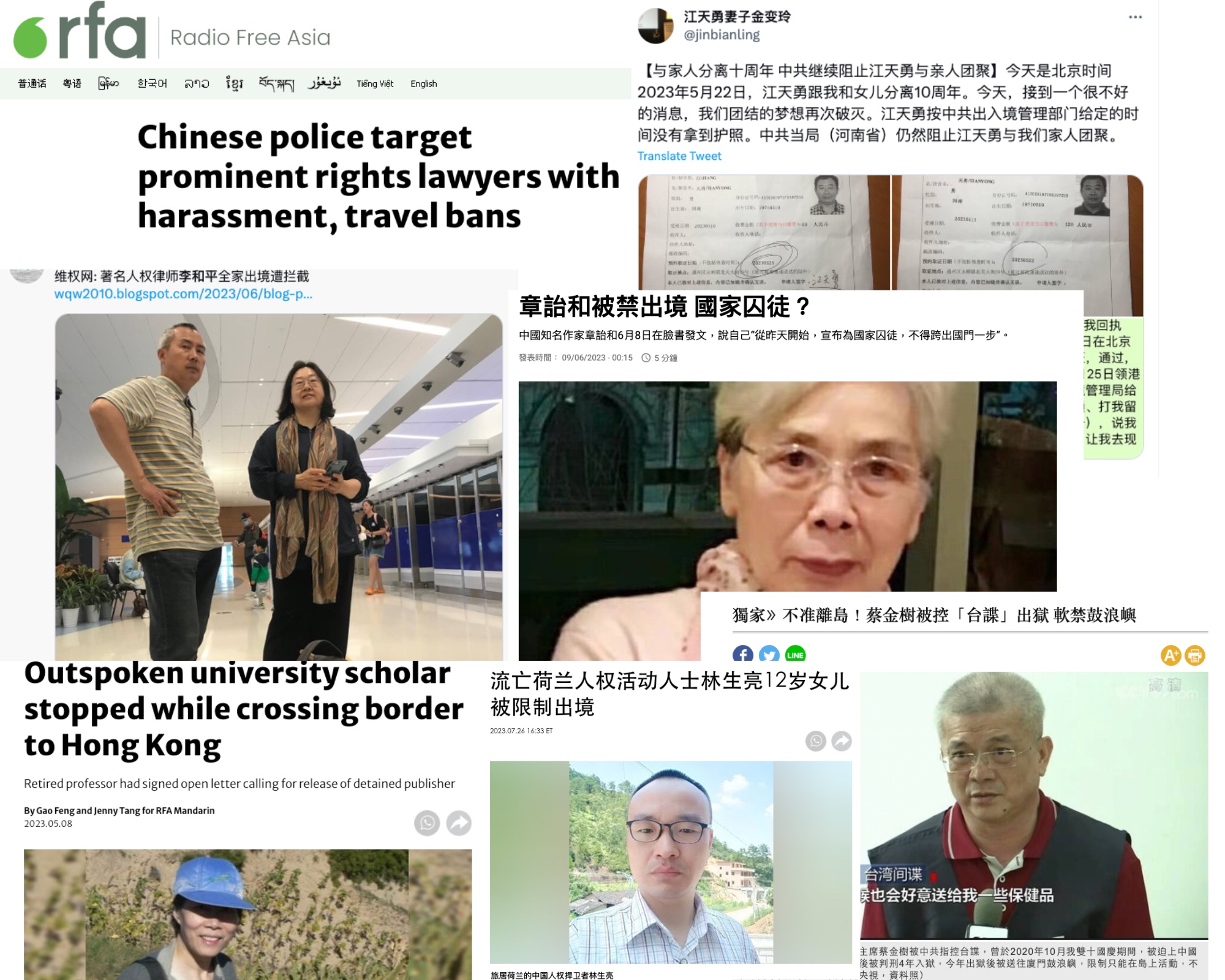

- Kwon Pyong, an ethnic Korean Chinese citizen, who had earlier been imprisoned for wearing a T-shirt that mocked Xi Jinping, was so desperate to escape China and his exit ban that he risked his life by travelling on a jet ski to South Korea.

- Lin Yujun, the 12-year-old daughter of exiled Chinese rights activist James Lin, was stopped at the border as she tried to cross into Hong Kong with her aunt.

- Zhang Yihe, a distinguished writer in her 80s, was told that she would not be allowed to leave on a trip to Europe that she had planned this summer.

- Cai Jinshu, a Taiwanese academic that had just completed a four-year-sentence for spying, is basically under island arrest inside China.

- Li Heping, a renowned human rights lawyer and his family were stopped at the airport from going on a summer holiday to Thailand.

On 1 July, the amended counter-espionage law came into effect, making the total number of laws that authorize exit bans in China to at least 15. The revised legislation allows exit bans to be placed on anyone (Chinese or foreign) suspected of espionage and on Chinese nationals if the authorities believe they may harm national security after they leave China.

Even while police continue to harass political targets, such as human rights lawyers and their families and outspoken scholars, including through forced evictions and oppressive surveillance, Beijing is increasingly unwilling to let them leave the country. This means that they essentially have nowhere to go.

Human rights lawyer Lu Siwei was so desperate to join his wife and young daughter in the US, that he escaped into Laos. Unfortunately, he was arrested by Laos police, despite having a valid visa, and it is feared he will be deported to China.

Banned from leaving

On 8 May, Guo Yuhua, a retired sociology professor and her husband tried to cross the border to Hong Kong when they were stopped by border officials, who told her Beijing police had put her under an exit ban. Guo had signed an open letter in 2020 calling for the release of a jailed publisher Geng Xiaonan.

In late May, the wife of human rights lawyer Jiang Tianyong tweeted that he still had not been issued with a new passport. The two have been separated for more than 10 years.

Then on 9 June, Li Heping, his wife Wang Qiaoling and their daughter were about to fly to Thailand together when they were stopped at the airport. Police told them they couldn’t leave on “national security” grounds, a common excuse given to human rights defenders and their families to justify exit bans.

Also in June, Zhang Yihe, a writer and historian in her eighties, was told at an event organized by the Ministry of Culture that she wouldn’t be allowed to leave the country for the foreseeable future. She had planned a trip to Europe in July.

And Cai Jinshu, a Taiwanese scholar who had served four years for spying was prevented from going home on the grounds that he had also been given four years of Deprivation of Political Rights. He is currently unable to leave Gulangyu Island in Xiamen city, which faces Taiwan in China’s Fujian province.

In August, media reported on a daring escape. Chinese activist Kwon Pyong, who was stuck in China on an exit ban after he was released from prison for wearing a t-shirt that mocked Xi Jinping, risked his life by escaping China on a jet ski. He was picked up in Incheon, South Korea, wearing a lifejacket and helmet and carrying a compass, binoculars and barrels of spare fuel.

According to an August tweet by Li Wenzu, the wife of human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang, she has unsuccessfully been trying to sue Baodong County police who have refused to approve her passport application.

Trapped: China's expanding use of exit bans

In Trapped, we analyzed new laws and conducted interviews with victims to explore how China is increasingly resorting to exit bans to punish human rights defenders and their families, hold people hostage to force targets overseas to come back to China (a practice called persuade to return, a form of transnational repression), control ethnic-religious groups, engage in hostage diplomacy and intimidate foreign journalists.

Many people find out they cannot leave the country only when they arrive at the airport. Often no reason is given, and channels to challenge the ban are either non-existent or ineffective.

In the absence of transparent official data and excluding ethnicity-based exit bans, which number in the millions, we estimate that at least tens of thousands of people in China are placed on exit bans at any one time. Many of these exit bans are illegitimate and violate the Universal Declaration of Human Right’s principle of Freedom of Movement.

Following the release of our report, global media have paid more attention to the growing risk of exit bans for both Chinese and foreigners, including this article, which provides guidelines on how to assess your risk and what to do if you find you are banned from leaving.

Read Trapped: China's Expanding Use of Exit Bans here.

Download the Executive Summary here.