A Chinese horror story: rights defenders punished in psychiatric prison

Jie Lijian’s heart pounds in panic whenever he sees a doctor in a white coat.

Jie Lijian’s heart pounds in panic whenever he sees a doctor in a white coat.

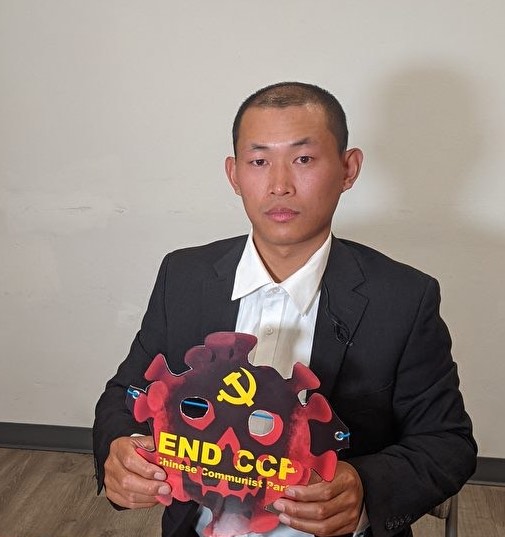

Four years ago, in the summer of 2018, Chinese police illegally locked this young rights defender up for 52 days in a psychiatric hospital simply for calling for the release of jailed workers and students.

Being drugged, abused, subjected to electroshocks and locked up on a mental ward was so traumatic that when he was released, Jie fled China. He was terrified police would send him back. Today, he lives in exile in California, where he continues his rights activism work with the Chinese Democracy Party.

Today, we are releasing the first Chinese translation of Drugged and Detained: China's Psychiatric Prisons and the updated English report (first released this August) to include Jie’s horror story including a sketch of his psychiatric detention ward and an hour-by-hour account of what life was like inside.

Please download updated version of Drugged and Detained (EN) here

Please download Chinese version of Drugged and Detained here

This was Jie’s third time forcibly hospitalized by the police, his first political forced hospitalization was when he was just 17 years old. This is common, many of the victims in the report said they had been sent back repeatedly.

We also used secondary sourced interviews of victims and their families and found 99 people had been locked up in psychiatric wards 144 times in the seven years from 2015 to 2021, covering 109 hospitals in 21 provinces, municipalities or regions across China. A significant number were sent back multiple times, in some cases more than a dozen, while others were kept for years, even for more than a decade.

Jie’s testimony is valuable as many victims still live in China and are therefore too scared to speak out. He told us that:

- Staff were intentionally cruel. They forced other patients to watch painful ECT procedures

- Staff were well aware that Jie and other rights defenders were political prisoners and openly cooperated with police in illegally admitting them

- The ward was suicide proofed, hard surfaces padded and patients weren’t even given chopsticks at meals

- He was likely only released because he tried to kill himself

Jie's third incarceration was in Shenzhen Kangning Hospital, a modern facility in the economic boom town of Shenzhen just across the border with Hong Kong. Kangning Hospital cooperates with western institutes, including King’s College London and University of Melbourne.

Like many other victims, Jie was not given a psychiatric evaluation when he was admitted – something that is against China’s mental health law. In fact, Jie overhead the police telling the hospital staff to watch him extremely closely because he was “trouble”.

The ease with which the doctors cooperated with the police indicates that many such “mentally-illed” victims have been sent there before, believes Jie.

Kangning had two separate areas for sectioned patients, one for self-paying and the other, where he was kept, for those sent by the police, some of them homeless people, and others who were activists and petitioners like him.

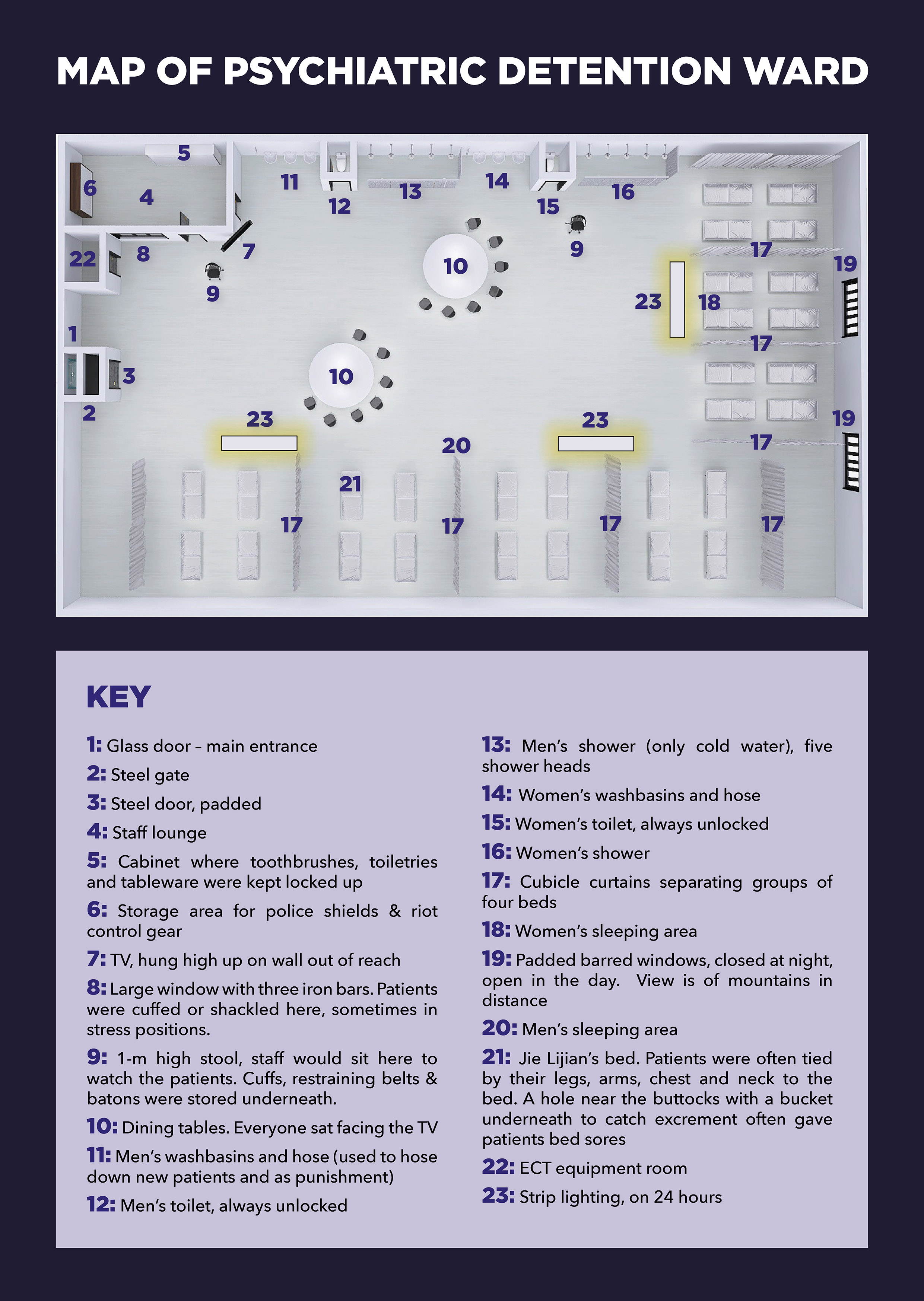

His ward, on the ninth floor, was a large hall where around 30 beds in groups of four were partitioned off with curtains that were closed at night and opened during the day. Iron bars were on the windows. There was also a recreation and dining area that they were allowed to use sometimes, where they ate and there was a TV.

The area was suicide-proofed. Most of the hard surfaces, such as the edges of tables and benches, were covered in a soft, spongy material. The bathroom door had no locks so staff could always enter. The ceilings were extra high; the light fittings could not be reached and the TV was attached out of reach high up on the wall. They were not given chopsticks, just plastic spoons and bowls, which were all kept in a locked cabinet between meals.

From day one, the staff forced Jie to take medicine – seven or eight types of pills. They never told him the names of the drugs they were giving him. “I’d feel really sick and then a bit dizzy and my sight would blur.” Initially, he tried to resist, but he was too weak. They tied him up and injected him with a sedative.

Each time a patient was given ECT, a staff member would wheel a cart with the machine and its wires into the wards. All the patients would be scared, because they knew how painful it was. “The women would cover their eyes and start screaming,” Jie remembered. But the staff would force the other patients to watch.

He was given electroshock therapy three times during his 52-day illegal psychiatric detention. Each time without any anaesthetic. The procedure was intensely painful.

They strapped him down with belts on his legs, his arms, his chest and his neck. The more he struggled, the tighter his bindings became. They placed a gag in his mouth to stop him biting his tongue. He described how they would use the same device to forced feed him medicine or force feed patients that were on hunger strikes.

They would place two electrodes on either side of his head, and his body would jerk uncontrollably. He would go in and out of consciousness.

Sometimes ECT would cause him to lose control of his bladder and the nurses would strike him because they were annoyed at the extra work.

When he woke up, he would vomit blood and bits of food. He felt very sick. “It was like dying,” he said

Inside Kangning hospital, Jie’s days were filled with fear and pain.

“It was torture,” he said. “I would have preferred to die than carrying on living there.

There was no way to leave. And I wanted to die.”

In desperation, Jie decided to try and kill himself by smashing the top of the toilet tank and slashing his wrists with the jagged pieces of porcelain. He had been thinking about it for a long time. He succeeded in cutting himself, but the staff discovered him and he didn’t die.

However, his suicide attempt frightened the hospital; they didn’t want his blood on their hands.

Fifty-two days after he was first forcibly hospitalized, Jie was released into police custody. Once he was free, he decided that the experience in Kangning had so frightened him he had to leave China. He was too afraid of being sent back.

Today, Jie lives in California and still suffers from health issues, such as severe head pains and uncontrollable shaking which he believes stem from his forced hospitalization. He continues to suffer panic attacks whenever he sees police cars drive by or medical staff in white coats.