Continued increase in Chinese Asylum-seekers despite COVID

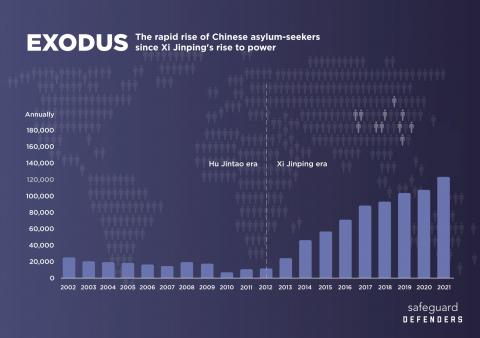

New data released today from the UN’s Refugee Agency, UNHCR, which also collects data on asylum-seekers, shows that year by year since Xi Jinping came to power, in lockstep with a more oppressive system of governance, the number of asylum-seekers from China has continued to grow at an alarming rate. In 2020, and now with new figures just released for 2021, it shows continued growth despite COVID restrictions.

Since Xi Jinping took power in 2012, Chinese economic growth may have slowed down as China entered the world of middle-income nations, and since at least 2017 also run into structural issues forcing ever-larger stimulus input to keep growth going, but nonetheless, China has continued to deliver a strong foundation for people to economically improve their lives, barring the current COVID lockdowns. Despite this, asylum-seekers continue to increase, with no end in sight.

At the start of Xi Jinping’s reign, in 2012, some 12,000 Chinese sought asylum. By 2019, that figure surpassed 100,000, and despite travel restrictions both in China and worldwide, it continued to increase both 2020 and 2021, now reaching nearly 120,000 people last year - ten times the number of asylum seekers the year Xi entered power.

In one year of Xi Jinping’s rule, 2021, China has now had more asylum-seekers than during the last eight years of his predecessor Hu Jintao’s rule.

In fact, since 2012 China has seen some 730,000 people seeking asylum. Another 170,000+ persons are living outside of China under refugee status, although the number of refugees has held steady for a long time (many of whom are Tibetans living in India).

The new data from UNHCR points towards a continued escalation.

The asylum data alone is too limiting to draw conclusions about whether Chinese people are to a greater extent "voting with their feet" or not. The current COVID pandemic also means there is little use in looking at broader immigration data to identify any pattern to support or oppose such a view.

What is known is that seeking asylum is for many a desperate act, reserved for those with few other options, which does not apply to the great many Chinese who have moved, and continue to do so, to the U.S, Australia, and beyond, often via naturalization, work visas or property purchases.

Where do they go?

The United States remains by far the most popular choice, with 88,722 persons seeking asylum there. The only other place that has been consistently popular is Australia, which saw 15,774 asylum-seekers last year.

Canada, Brazil, South Korea, and the UK also see Chinese asylum-seekers in the thousands.

Europe, outside of the UK, remains far less popular, with Spain taking in 900, compared to Germany’s 379 and France’s 248. Many European countries have received zero asylum-seekers, which also applies to most of Asia, all of Africa except South Korea and Egypt, and most of the Middle East.

With a greater number of asylum-seekers, the risk of Chinese transnational repression, including its use of Involuntary Returns, grows, and it was noted that China announced an expansion of its SkyNet program earlier this year, which seeks to force the return of claimed fugitives, and a program credibly accused of being part of China’s overseas work with transnational repression.