Disappeared by China: Taiwan activist Lee Ming-che describes his black jail

“It was hard not to lose your mind.”

“It was hard not to lose your mind.”

That’s how Taiwanese pro-democracy activist Lee Ming-che described his two months hidden from the world inside China’s secret jail network, called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL).

“Those two months were the worst, you don’t know if your family are ok; you don’t know what’s going to happen to you,” Lee remembered. “It was really frightening and very hard to deal with. There’s absolutely nothing you can do.”

Lee, an NGO worker from Taipei, was disappeared by police moments after he crossed Macau’s border with mainland China in Zhuhai in March 2017. He spent the next two months in RSDL, he believes in a secret facility in Guangzhou in the same province of Guangdong as Zhuhai. He was then transferred to a detention centre in Hunan province. At his open trial later that year, Lee was sentenced to five years in prison on trumped up charges of subversion of the state.

Those five years passed, and in April this year, Lee flew home to Taiwan and his wife, who had campaigned tirelessly for him.

Locked Up in RSDL

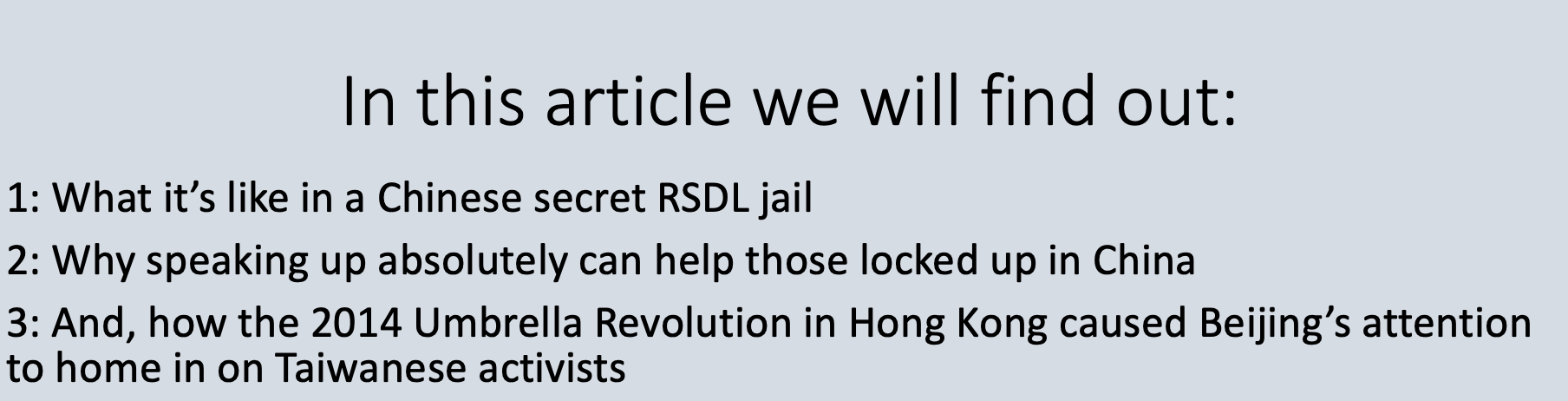

Lee’s two month’s detention in RSDL shares many similarities to that of other victims we documented in our 2021 ground-breaking report Locked Up: Inside China's Secret RSDL Jails.

- When Lee was disappeared, he was surrounded by about 10 plainclothes officers who said they were from Zhuhai police. They forced him into the back of a car with a black bag put over his head so he could not see where he was going, nor the RSDL building itself

- No RSDL notice was ever delivered to his family or Taiwanese authorities

- His RSDL cell was plain, the only piece of furniture was a bed

- He was watched 24-hours a day by two guards working in three shifts, even when he went to the bathroom

- The window was covered by a dark curtain so he could not see the outside, although he said he could tell by the light coming through the fabric whether it was day or night.

- His RSDL location was kept a secret from him

- He was mentally tortured through indirect threats. His interrogators would say things like: “Your family are now elderly don’t you miss them? if you don’t explain everything you did clearly, then you might never get to see your parents ever again”

THE RAID, DAILY LIFE AND TORTURE METHODS IN RSDL. TAKEN FROM LOCKED UP GRAPHICS REPORT. MR. LEE'S RSDL SHARES SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES WITH THE ABOVE.

- His interrogations took place in the adjoining room to his cell, which was open plan. This is against Chinese law; interrogations may not take place in the same facility as the RSDL

- He had no distractions for the entire two months. “There was nothing to read at all,” said Lee. “It’s a kind of mental torture having nothing to do”

- His interrogators were from the Ministry of State Security

However, also like some of the other foreigners who have been kept in RSDL, Lee’s detention, while frightening, was not as harsh as those experienced by local Chinese victims

>> He did not stay for the full six months

“Actually, I was quite lucky, because my RSDL only lasted two months,” said Lee. “Then I was taken to a detention centre and my life became a bit more normal.” Even though the material conditions in the detention centre were worse – food and bedding – at least he was not disappeared in a black hole, he could speak to other human beings who weren’t his captors.

Other RSDL victims have been locked up for the legal maximum of six months, even -illegally - longer in some cases.

>> He was not physically tortured

Other RSDL victims have been beaten, sleep deprived, food deprived, made to sit for hours on an excruciating “dangling chair”, shackled with heavy leg irons and cuffs and even forced to ingest unknown drugs.

“Apart from the interrogations, I could lie on the bed and sleep whenever I wanted and they’d leave me alone,” said Lee, who added he was given timely medication for his blood pressure and ate well compared with other RSDL victims. “I ate exactly what my guards and interrogators ate,” he said. “The only thing I was never given was fish, because fish have tiny bones.” He could have used one to commit suicide.

>> His cell was not suicide-proofed

Apart from not giving him fish and watching him 24-7, there were no other anti-suicide measures enforced during his RSDL.

Other RSDL victims reported having padded walls, padded furniture, even specially designed toothbrushes so they couldn’t swallow them and kill themselves that way.

>> There was no long list of rules to obey

“Apart from the interrogations there was nothing I had to do, no rules,” Lee said. “In the beginning, they didn't allow me to move around. I protested a few times, so they allowed me to walk around in the interrogation room for a set period of time.”

Other victims had to stay within a small area marked out by a square drawn on the floor. They weren’t allowed back in their beds unless it was bed-time.

Secret locations

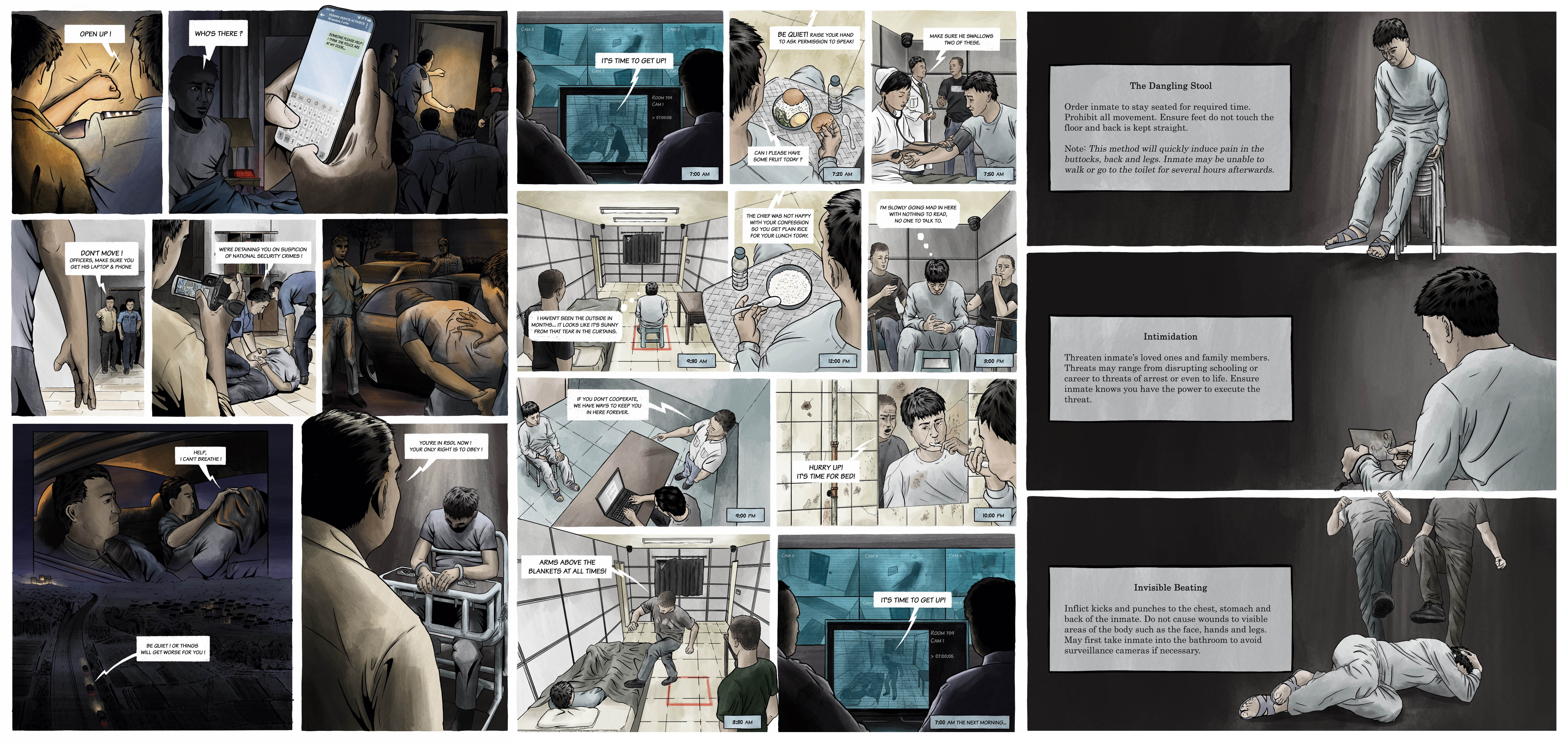

RSDL by design is a secretive jail system. Lee does not know exactly where his RSDL jail was but he guessed it was in Guangzhou for several reasons.

RSDL by design is a secretive jail system. Lee does not know exactly where his RSDL jail was but he guessed it was in Guangzhou for several reasons.

- It took about two hours to drive from Zhuhai to the facility, which would put Guangzhou in the range of possible locations

- A doctor, who was sent to check his blood pressure when he arrived, had a form of identification that named him as a doctor from a Guangzhou hospital

- And, he often heard the sound of gunshots outside so he assumed he was at some kind of police or military training centre

Back in Taiwan, Lee checked our report, Locked Up, and believes that he was held at the same facility as human rights lawyer Sui Muqing. Sui identified it as Guangzhou Public Security Bureau People's Police Training Centre, Dashi Town, Panyu District, Guangzhou.

Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution was a Turning Point

Before he was disappeared, Lee had been travelling back and for between Taiwan and China for years, meeting rights defenders and discussing Taiwan’s democratic evolution. He was always careful to keep low-key – never meeting high profile figures and keeping everything small-scale. Until that day in March 2017, he had never been detained or questioned in China.

Before he was disappeared, Lee had been travelling back and for between Taiwan and China for years, meeting rights defenders and discussing Taiwan’s democratic evolution. He was always careful to keep low-key – never meeting high profile figures and keeping everything small-scale. Until that day in March 2017, he had never been detained or questioned in China.

He says things began to change in 2014.

That was the year huge protests broke out in Hong Kong over Beijing’s decision not to allow the region to move towards universal suffrage. Pro-democracy protesters used umbrellas to protect them from police pepper spray, making the umbrella a symbol of their movement.

The scale of the Hong Kong protests unnerved Beijing. The CCP leadership began to suspect that Taiwanese activists wanted to make Taiwan’s democratization a reality in China. “So they started to pay attention to any Taiwanese NGO that was in contact with Chinese activists or Hongkongers,” said Lee.

In 2016, in a trip to China, one of Lee’s contacts organized a large meeting without his knowledge. That, he believes, put him on the Chinese authorities’ radar. Coupled with their paranoia over Hong Kong and Taiwanese NGO workers, the next time he visited China, the police were waiting for him.

The power of speaking out

While Lee was disappeared, locked up in RSDL, locked up in detention, and then locked up in prison, his wife Lee Ching-yu, who is also a human rights activist, was indefatigable in campaigning for her husband’s release.

While Lee was disappeared, locked up in RSDL, locked up in detention, and then locked up in prison, his wife Lee Ching-yu, who is also a human rights activist, was indefatigable in campaigning for her husband’s release.

She spoke to media, went to the US and Europe to speak on behalf of her husband, and even got Lee’s case to be the first from Taiwan to be accepted by the United Nations Human Rights Special Procedures.

Lee believes that this is likely the real reason his treatment was not as bad as it could have been, although he was sentenced to a harsh five-year jail term, which he served in full.

His wife’s activism kept Beijing alert to international criticism of his case and may have helped in:

- Ensuring he only stayed in RSDL for two months, not the usual six months

- That his trial was open, and his family members were allowed to attend. “Since Xi Jinping came to power, he started to use the charges of Subversion of State to detain a lot of human rights defenders, but I was the only one with this charge that was given an open trial,” said Lee.

- In prison, he was allowed to have the legally mandated rest day (the remainder were five days of work, one day of classes). Other sections of Chishan Prison, where he was held, did not observe the legally-mandated rest day and prisoners worked six days a week.

- He was allowed to leave China once his prison term was completed. At least one other Taiwanese former prisoner in China – Morrison Lee – is stuck in China unable to leave because although he was released from jail, he must still serve his two year’s deprivation of political rights.

This is key to guiding the global response to other disappearances of foreign nationals.

In most cases, quiet diplomacy does not work, it is essential to speak out for prisoners of conscience and pressure Beijing for their release or at the very least, demand more humane treatment.

For that to happen, we need to be as open and transparent and honest as we can. Stories like this on our website not only help to act as a record of CCP abuse and a help to others in preparing for their possible capture, but they are evidence that should be used to hold Beijing accountable.

As Lee said in his parting words to us after our interview:

“If you think that my case or information about my case can help human rights in China then please ask me anything and I will tell you.”