Liuzhi system expands in use amidst reforms

New data from the CCP itself shows the system expanding rapidly in scale, amidst changes to regulations allowing for solitary confinement at secret locations from the current six up to 16 months, following revisions to law in June.

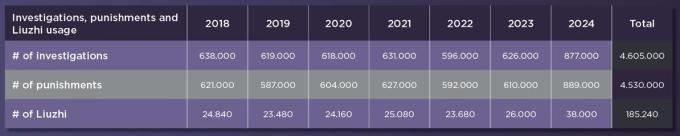

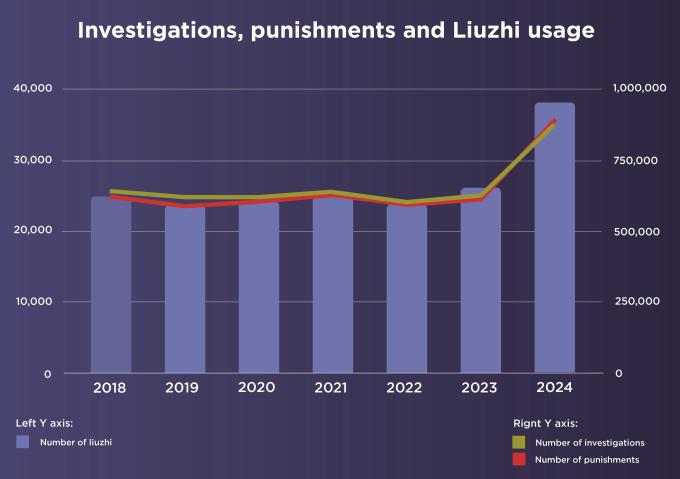

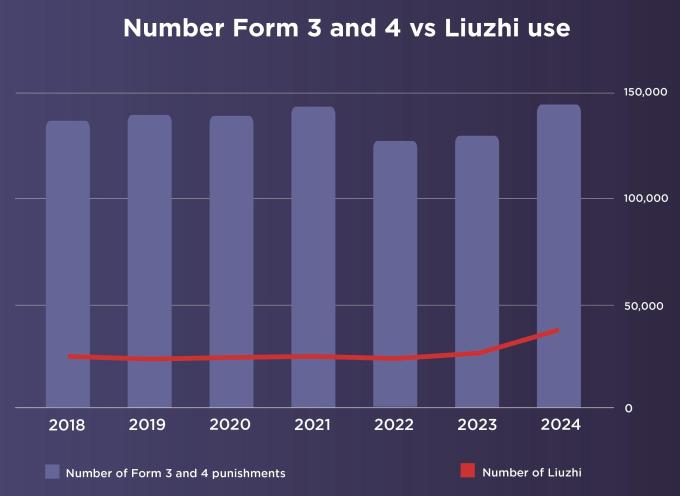

Data from the Chinese Communist Party’s internal discipline watchdog (CCDI) from 2025 shows a record 46% increase in the use of the feared Liuzhi system between 2023 and 2024, to new record high levels.

However, data from both 2024 (for 2023) and 2025 (for 2024), the first time the body has ever released (claimed) nationwide use of the Liuzhi system, also has much more to offer.

While occasional data has in the past been released on the use of Liuzhi, since the system came into effect March 2018, it has been limited either to its use in a few select provinces, for limited time-periods, or for specific campaigns, never in its full use.

CCDI - The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Commission for Discipline Committee (CCDI) is tasked with ensuring compliance, political correctness and loyalty within the Party’s 95 million members. The CCDI’s main work is carried out by Commission for Discipline Committee (CDI’s) on provincial levels and further below.

Despite this lack of data, by collecting the fullest possible data sample, SD has been able to make estimates on its use, using both lower and higher estimates, to get a range, and the new data not only proves those estimates to have been correct, but also, that it has been the higher estimate that has been consistently correct.

Liuzhi - retention in custody is part of an internal CCP system for detention and investigation and is not part of the State’s criminal justice system. While in Liuzhi, which is decided upon by the CCDI itself, without any external body to supervise or approve, the person must, by regulation, be kept in solitary confinement, have no access to legal counsel (as this is by definition not a legal process) and may be kept from any form of communication. The target is, by design, held incommunicado. The locations used vary, from custom-built facilities to Party-run hotels, guesthouses, offices etc. The location shall not be shared, meaning the person is, by any definition, disappeared. This period of detention can last six months. There is no external appeal mechanism.

Using the 2023 and 2024 data, where 26,000 and 38,000 investigations utilized the Liuzhi system, and comparing that with the total number of investigations in those years (626,000 and 877,000) respectively, SD can for the first time know the percentage of investigations that utilized the system, namely 4.15 % and 4.33%. For more information on the recent data, and what kind of people and groups have been targeted, see SD’s prior post here.

Knowing both the total number of investigations for each year since 2018, data which is made available, and now knowing that at least around 4% of those involve Liuzhi, and that the number of investigations have remained fairly stable, and there is no reason to believe the percentage of use of Liuzhi would have changed drastically, we can get better estimate on its use prior to the Party started releasing full data (after 2023).

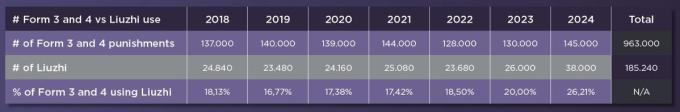

Assuming an average of 4% use of Liuzhi for 2018 to 2022, the following estimates can be made:

This would place the use of Liuzhi – and thus enforced disappearances and arbitrary detention – at over 185,000 cases since the inception of the system, making it both, by any stretch, systematic and widespread. The use of disappearances and arbitrary detention, if systematic or widespread, may amount to a crime against humanity, per articles 7e, 7f, 7i and 7k of the Rome Statute.

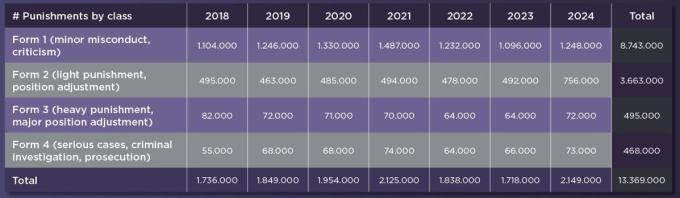

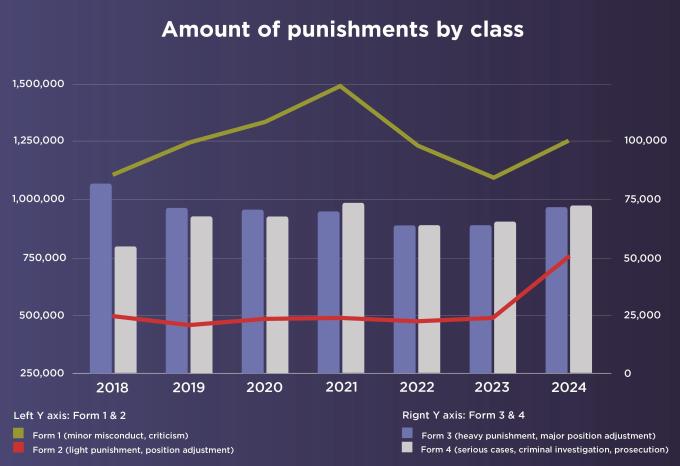

For a further deep dive in what this data gives us, SD has also analyzed the different forms of punishments meted out as a result of the investigations.

One way of measuring the likely use of Liuzhi in the past has been to look at form 3 and form 4 punishments (the strongest types) and estimate that 10% to 20% of those have involved use of Liuzhi, for a low to high estimate. A version of this method was first developed by former CCDI staffer and scholar Li Yongzhong back in 2013. Applying our adapted method shows that in the end, again, the high estimate is the one that has been most correct, and that the percentage of Form 3 and 4 punishments that have utilized Liuzhi has increased over time, to a record high in 2024.

While the scale of use of the Liuzhi is not very different from SD’s prior estimates and extrapolations, the difference is that the data underpinning it is now far greater, and for 2023 and 2024, irrefutable, as it is the full (claimed) use of Liuzhi as stated by the CCP itself. Likewise, the data also shows that for 2018 to 2023, SD estimates have been consistently correct, and that it is its high estimate has been the correct one.

If one was to be exceedingly cautious and only rely on the number of Liuzhi cases that the CCP has officially acknowledged, looking at very limited, province-based data, and only for select periods of each year, for 2018 to 2022, coupled with the now officially recognized nationwide data for 2023 and 2024, the total number of disappearances and arbitrary detentions stands at 76,501.

Alongside this increase in the number of victims held in Liuzhi, there has also been a significant effort to both build new Liuzhi facilities, and upgrade and expand on existing ones, as reported on by CNN in December 2024, with research drawing on official procurement documentation. That research showed the construction or upgrade of over 200 facilities across the country, with the largest number being in 2024, and with a clear upward trend after a temporary halt in its use during the era of COVID-19 restrictions.

Nothing indicates that the number won't continue to grow, and 2025 is likely to see yet another new record number of victims disappear into the system.

By far the most damaging revision that went into effect this summer (June 1) was two new additions which allow the CCDI (since 2018 also referred to as the NCS, or National Supervision Commission) to hold those placed into Liuzhi longer, and weaken the prior 6-month limit. Now, with one new clause, Liuzhi can be extended by two more months, for a total of eight months, if the possible crime they are being investigated for could carry a prison sentence of 10 years or more.

However, compounding this is the fact that a case run by the central CCDI/NCS, or provincial level CCDI/NCS, may “reset” the time spent in Liuzhi if the investigators identify a new serious (claimed) offense during the investigation, which would mean that a person can be kept - continuously - for 16 months.

In addition to extending how long Liuzhi can be used, several other measures that the CCDI/NCS can take have been added, such as:

compulsory appearance (24 hours of questioning),

confinement (7 days of emergency detention - for the victim’s protection)

protective care (7 to 10 days, a shorter-term version of Liuzhi)

release pending investigation (restrictions on personal freedoms for up to 12 months)

A few additional revisions have moved the regulations more closely in line with the language used in the criminal procedure law, but without having any meaning, as there is no supervision or oversight of the system, nor any legal basis for challenging it. Some rosy words on respecting human rights, while added, are unlikely to change anything for those inside Liuzhi.

Despite this new round of revisions, what remains, however, is the complete lack of appeal outside of the CCDI/NCS itself, the right by the CCDI/NCS to now take someone away into secret detention for 16 months and still not notify the victims’ family, nor, of course, any external oversight of the CCDI/NCS and how it operates the Liuzhi system.

Liuzhi remains a black hole, where the victims are entirely powerless.

With aforementioned irrefutable data, and the very design of the system itself, which not only constitute enforced disappearances as well as arbitrary detentions (as it is not part of any legal process), alongside the UN General Assembly’s decision that the use of solitary confinement for prolonged periods (more than two weeks) when used for investigatory (not disciplinary) reasons constitute both inhuman and degrading treatment (article 16 of the Convention Against Torture) and torture (article 1), SD on July 6, in a formal submission, called on the UN Working Group on arbitrary detention, the UN Working Group on enforced or involuntary disappearances, and the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, to, as they did with the similar RSDL system in 2018, forcefully and directly call out the system on these grounds.