China’s Disappearing Officials: Common “Party Discipline” Practice

Ever wonder where all those high officials in China keep disappearing to?

Here’s the answer… and the increasingly frequent headlines on yet another Party boss gone missing don’t even begin to cut it.

They are but few of a whopping 26,000 individuals placed into the Chinese Communist Party’s notorious Liuzhi system in 2023 alone. Liuzhi, or retention in custody, is a special “investigative mechanism” that allows the Party’s internal police force (Central Commission for Discipline Inspection – CCDI) to forcefully disappear, arbitrarily detain and torture individuals for up to six months. All without any judicial oversight or appeal mechanism, the system is specifically designed to force confessions from the victims.

As former CCDI lead Liu Jianchao (since promoted to head of the International Liaison Department) put it: “These are not criminal or judicial arrests and they are more effective”.

A successor to Shuanggui, the system is another of the many hardening reforms since Xi Jinping assumed the helm of the CCP and rapidly started moving the country even further away from the most basic human rights standards to which it is beholden under international law.

Officially instituted under the National Supervision Law in 2018, liuzhi is rapidly catching up with other mechanisms of enforced disappearances in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Its use now appears to be on par with the use of Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL), instituted in 2014 and most often employed against human rights defenders.

On December 12, 2024, Safeguard Defenders (SD) submitted new data to relevant UN Human Rights Procedures on the systematic and widespread use of liuzhi across the PRC’s territory. Learn more about the system, its systematic and widespread use, the actors behind it and one UN agency’s ongoing cooperation with them in the summary below or by reading the full submission here.

The 2018 National Supervision Law (NSL) formally authorized the newly instituted National Commission of Supervision of the CCP’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (if that sounds like a confounding mouthful, it is supposed to – more on that later) to vastly expand the CCDI’s inspection mandate.

An important part of that investigative power resides in the faculty to forcefully disappear any person of interest for up to six months.

Per regulation, any individual placed inside the system must be held in solitary confinement. The vast majority of victims are kept from any type of communication with the outside world and their family members are not informed of their whereabouts (or even the retention itself) as the system makes use of undisclosed (designated) locations, from custom-built facilities to CCP-run hotels, guesthouses, offices, etc. By any definition, it is a system of Party-state sanctioned incommunicado detention.

As the system exists wholly outside the bounds of the PRC’s formal criminal justice system, there is no external entity to provide independent oversight, approval or review of a decision to place an individual into the system, nor do victims have the right to access legal counsel.

The reasoning behind it all is very simple: to break the victims down. As a Professor at Peking University explained: [These cases are] “heavily dependent on the suspect’s confession. (...) If he (the suspect) remains silent under the advice of a lawyer, it would be very hard to crack the case”.

**

Testimonies from inside liuzhi (or its predecessor shuanggui) are rare, but all agree: "It looks very nice. But it is the worst place in the world." - Jean Zou, a shuanggui victim.

“The rooms mostly looked normal, with all the expected facilities — bathroom, tables, sofa, she said in an interview. The only sign of the room’s true purpose was the soft rubber walls. They were installed because too many officials had previously tried to commit suicide by banging their heads against the wall” – description of a facility in Shanghai by Lin Zhe, professor at the Central Party School.

"Their requirement for us doctors was to keep them safe. That meant, don't let them die. A dead person would create big problems. Someone who is only injured doesn't matter." -Testimony.

“[He] sought to kill himself by biting through the artery in his wrist. He was stopped by members of the team of dozens keeping constant watch over him. Some were doctors, tasked to ensure he was kept alive.” - Testimony.

**

Ostensibly these measures are employed to root out corruption in the PRC. Yet the CCDI’s work regulations clearly tell another story. “Corruption” in the PRC is as much about securing loyalty to the Party’s central leadership with Xi Jinping at its core, as it is about what a democratic audience would understand the term to mean: "adhering to the overall leadership of the Party and the centralized and unified leadership of the Party Central Committee" is the primary principle that the Commission for Discipline Inspection must follow in carrying out its work.”

As a The Guardian article from this December 16 spells out: “As the situation and tasks facing the party change, there will inevitably be all kinds of conflicts and problems within the party. We must have the courage to turn the knife inward and eliminate their negative impact in a timely manner to ensure that the party is always full of vigour and vitality.” Words delivered by Xi Jinping at a CCDI meeting in January 2024.

Until the start of this year, one could only made educated guesses at how many individuals had been placed in liuzhi since 2018.

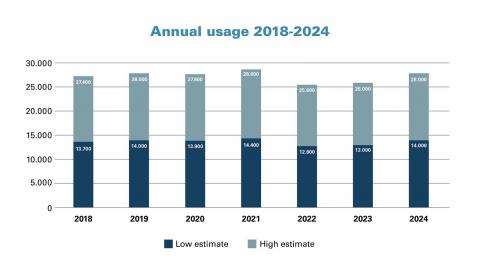

In January 2024, for the first time since the system’s formal inauguration, the CCDI published official data on its use: no less than 26,000 individuals had been placed inside the system in 2023 alone!

That is an average of 71 people being forcefully disappeared, arbitrarily detained and subjected to torture in liuzhi alone… Every. Single. Day.

The scary part: the 2023 number corresponds exactly to the worst-case high estimates Safeguard Defenders had made for previous years, based on partially available data from provincial Discipline Inspection Committees and punishment statistics.

(If you’re interested in the full explainer on our methodology and the numbers underpinning such estimates, please see pages 7 to 9 of our latest submission to relevant human rights procedures.)

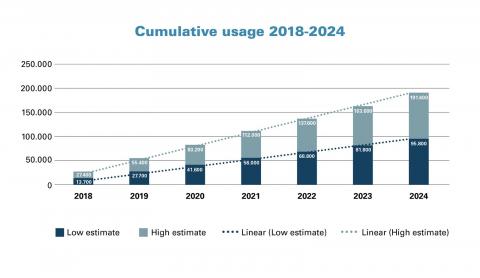

It is too early to assess whether such worst-case high estimates can be confirmed over time, but a most conservative estimate would put the number of victims between 2018 and 2024 at 95,000. Based on the same methodology, the high estimate (confirmed by official data for 2023) arrives at a steep 190,000 victims between 2018 and 2024.

Cumulative usage since the inception of the system in 2018 would, using the same low v. high estimate, arrive at the following totals.

*2024 extrapolated to a full year from data available for January to September.

Behind it all is everyone’s favourite non-state entity: the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party of China (CCDI). An internal Party police force placed outside any state control or oversight, mandated to control (inspect) and punish (discipline) any Party member.

But the aforementioned 2018 National Supervision Law not only granted the entity the power of liuzhi, it also vastly expanded the scope of the CCDI’s mandate by creating its state front: the National Commission of Supervision of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (NCS).

This hybrid entity is no longer limited to inspecting and disciplining CCP members only. Estimates based on a 2017 pilot run across three provinces indicate the number of potential targets for investigation likely rose to somewhere between 200 and 500 million individuals: from Party members and state officials to anyone working at or above management level within public institutions such as hospitals, schools, mass organizations or state-owned enterprises. Moreover, any person investigators believe might be of interest to an ongoing investigation on a person under their mandate can be subjected to the same treatment.

In 2023 alone, official data released by the CCDI tells us no less than 626,000 individuals were placed under investigation by the CCDI-NCS apparatus.

45-year-old Chen Yong was placed in liuzhi by the Fujian Supervision Commission on April 9, 2018.

At 8 PM on May 5, 2018, he was declared deceased. A mere six weeks after the National Supervision Law was promulgated.

Chen was not a suspect in the case under investigation. He was not even an individual under the mandate of the CCDI-NCS. He just happened to have worked for someone who was…

Until 2016, Chen was a chauffeur for the Jianyang District Government of Nanping City. When the District’s Vice-Director Lin Qiang was placed under investigation, Chen’s former position was enough to snare him up.

News of his death first appeared in media outlet Caixin but was quickly scrubbed by censors. However, that original report included witness statements from his family that leave little doubt as to what happened: on May 5th, nearly a month into Chen’s detention, his family received a summons from the authorities. This was the first time they had heard anything from the NCS or on where Chen had disappeared to.

Once they arrived at the specified location, they were taken into the morgue and shown their deceased loved one.

[He had] “a disfigured face. I pulled his shirt up and saw his chest was caved in. He had black and blue bruises on his waist. They stopped me when I tried to check his lower body,” his sister said.

His wife confirmed the statements after arriving later that evening. Yet, according to the authorities, Chen simply collapsed during an interrogation at 4 PM that day. After being rushed to the hospital, by 8 PM he had died. Family requests to review video recordings were denied.

But the CCDI’s malfeasances do not end at China’s borders. Anyone familiar with our work on the PRC’s transnational policing operations in over 120 countries around the world (as the CCDI annual reports tell us), may remember it is the very same entity that is responsible for overseeing these operations.

Moreover, it is the author of the 2018 written legal interpretation to the National Supervision Law that explicitly authorizes PRC entities to conduct such operations through covert means, including persuasion to return, luring and entrapment, and kidnapping.

And it is in that ambit that the creation of its state front, the NCS, becomes even more concerning.

Void of any proper offices, leadership, or personnel, it is the exact same entity to all extent and purposes. Yet with a simple name change, the CCP has successfully managed to sell its Party police force as the PRC’s main focal point for international cooperation. Including with the United Nations.

There’s a dual role for the UN in this scenario. Good guardian on the one hand, bad cop on the other.

UN Human Rights Procedures and Treaty Bodies have repeatedly denounced the system of liuzhi as tantamount to enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and torture or other cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. In a General Allegation Letter from earlier this year, the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances furthermore raised specific concerns with the Chinese authorities “regarding an alarmingly high number of extraterritorial abductions and transnational transfers (involving arbitrary deprivations of liberty and renditions) from the Mekong region and neighbouring countries of persons who end up in secret detention or other forms of deprivation of liberty. Moreover, information shared with the Working Group demonstrates a systemic pattern pursuant to which such practices are designed to pressure and to control dissenting groups seeking protection abroad, in cluding people belonging to ethnic and religious minorities, political dissidents, human rights defenders, journalists, refugees, and asylum seekers.”

As far as we are aware, the PRC has not responded to the Working Group’s queries.

For detail on the multitude of international human rights provisions violated by the practice and positions taken by relevant UN Procedures, please see our latest submission on the use of liuzhi.

At the same time, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has accepted the PRC’s designation of the NCS as its focal point for all work under the Convention Against Corruption, while engaging in technical cooperation with the body under the Memorandum of Understanding signed in October 2019.

You read that right.

UNODC continues to cooperate with an entity that by its own admission has engaged in the mass enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention and torture of 71 individuals every single day of 2023.

UNODC continues to cooperate with an entity that according to its own written legal interpretation engages in or encourages covert means of forcefully returning individuals to China, in blatant violation of other countries’ territorial sovereignty and the Convention Against Corruption.

UNODC continues to cooperate despite the mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence Policy on United Nations Support to non-United Nations Security Forces, which prescribes that “if the United Nations receives reliable information that provides substantial grounds to believe that a recipient of United Nations support is committing grave violations of international humanitarian, human rights or refugee law, the United Nations entity providing such support must intercede with the relevant authorities with a view to bringing those violations to an end. If, despite such intercession, the situation persists, the United Nations must suspend support to the offending elements.”

For more on UNODC’s apparent violation of UN policies and the content of its MoU with the CCDI (NCS), please read our April 2024 report Chasing Fox Hunt.

On a concluding note: corruption in the sense of the Convention Against Corruption is an actual and even endemic issue in the PRC. But combatting it is definitely not always the mandated agency’s first concern…

**

Extract from The Irish Times – May 1, 2020:

“A Chinese journalist and anti-corruption blogger has been jailed for 15 years after being accused of criticising the Communist Party through commentaries and investigative reports posted on social media platforms.

Chen Jieren has been detained since 2018 after he published two blog articles claiming corruption by Hunan party officials. Following his detention Chinese state media said Mr Chen's online reporting had "sabotaged the reputation of the party and the government and damaged the government's credibility".

Guiyang county court in Hunan province announced on Thursday it had finally convicted Mr Chen of "picking quarrels and provoking troubles", a charge that is often shorthand for criticising or challenging the party.

The court also convicted him of "illegal business activity", and extortion, blackmail and bribery, and fined him 7 million yuan (€900,000). His brother, Chen Weiren, was jailed for four years on the same charges. The court said the pair had posted "false and negative" information online "to hype relevant cases".”

Chen Jieren’s conviction came almost two years after he’d been forcefully disappeared upon instruction of the same local Commission of Supervision he had accused of corruption.