China is ramping up collective punishment of families

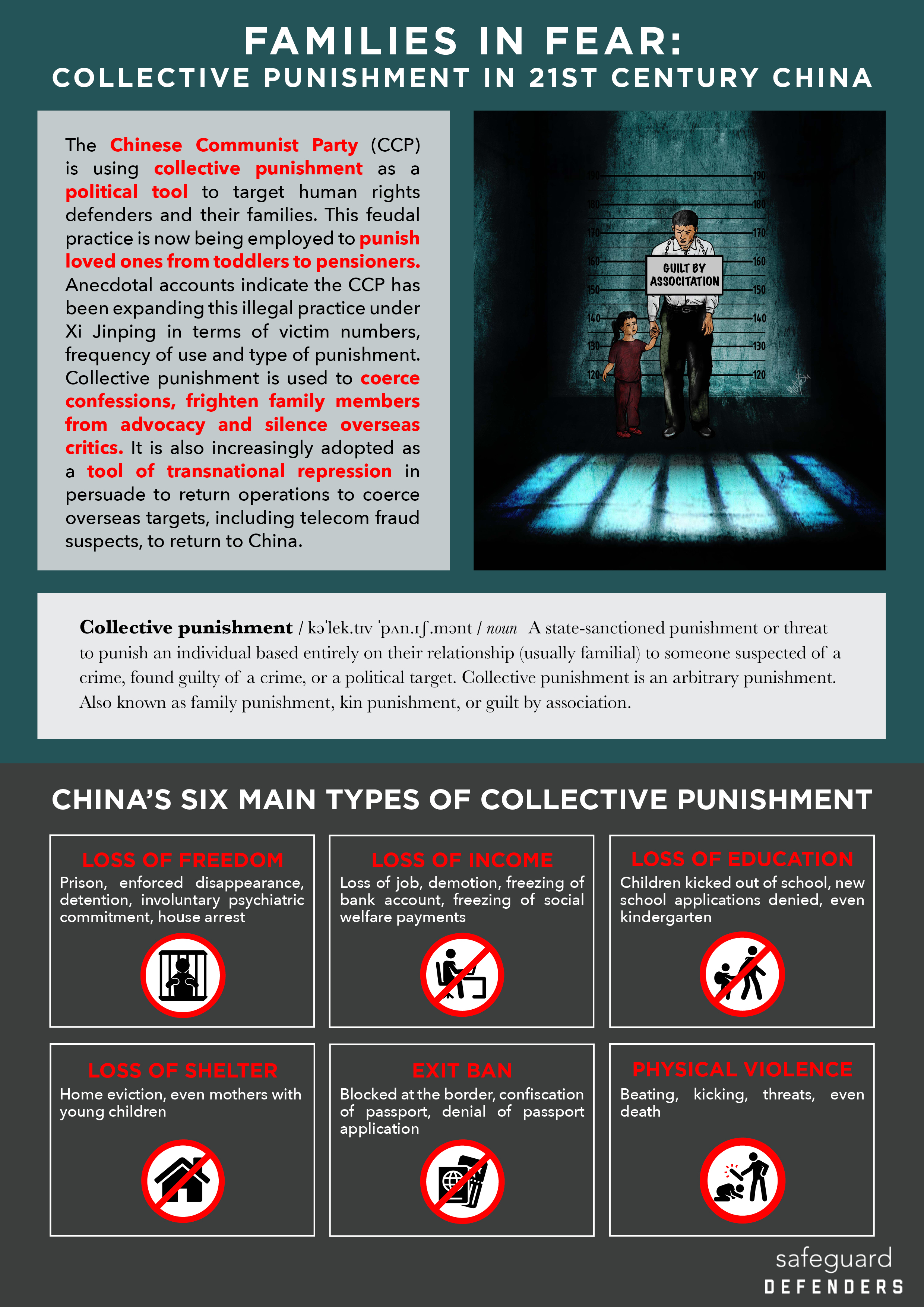

Under Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party is increasingly using collective punishment as a political tool to control human rights defenders and raise the personal cost of speaking up in China, according to a new report released today, International Human Rights Day.

Families in Fear: Collective Punishment in 21st Century China uses interviews and media reports to show how this feudal practice is being increasingly used both in terms of numbers and in type of punishment.

Download report here.

Download report here.

Download executive summary here.

No one is considered out of bounds: everyone from babies and toddlers to pensioners are being targeted.

Collective punishment is used to coerce confessions, frighten family members from advocacy and silence overseas critics. It is also increasingly adopted as a tool of transnational repression in “persuade to return” operations to coerce overseas targets, including telecom fraud suspects, to go back to China.

China’s CCP pressured the 70-year-old father of activist Yang Zhanqing’s to get his son to stop his rights work. After Yang, who lives in exile in the US, refused, his aged father lost his job and his home.

“Activists get used to this [CCP harassment] after being subjected to it so many times, but for people like my father, to them it’s like the world is ending,” says Yang.

Former miner Dong Jianbiao paid the ultimate price.

In 2022, he died in prison, his bruised body covered in blood. Police rushed through the cremation, forbidding the family their request for an autopsy.

The CCP punished Dong because his daughter splashed ink over a poster of Xi Jinping in 2018. She has since disappeared into the black hole of China’s illegal psychiatric detentions.

In Families in Fear, we break down the CCP’s collective punishment on human rights defenders into six basic types:

Loss of Freedom (including disappearance, detention, prison, psychiatric detention)

Loss of Shelter (home eviction)

Loss of Education (child kicked out of school)

Loss of Income (lost job, demotion, lost welfare payment)

Exit Ban, and

Physical Violence (beating, kicking and death)

Collective punishment is not a new thing in China. For thousands of years, various dynasties in China even executed innocent family members of those convicted of a crime. Despite it having no legal basis, the CCP has embraced it as a powerful political tool to control critics. And under Xi Jinping, testimonies from interviews describe how it becoming much more common, with a broader array of types of collective punishment.

The situation for some human rights defenders and their families has become so dire that one couple resorted to getting a fake divorce in order to escape punishment…

In December 2019, activist and musician Liu Sifang fled to Hong Kong in the middle of the night to escape arrest following his involvement in the Xiamen Gathering. This was an informal and private meeting of around 20 human rights lawyers and activists to discuss politics, but it sparked a nationwide crackdown on everyone involved.

He contacted his wife, Lu Lina, and asked her join him and bring their then seven-year-old son. Liu had just found out that some of his friends had been arrested and felt he had no choice but to go into exile.

The next day Lu and their son boarded a Hong Kong-bound train in Guangzhou. Liu waited for them at the Kowloon terminus in Hong Kong.

Neither of them imagined the CCP would stop a mother and her young son from travelling to Hong Kong.

“The CCP hadn’t been using collective punishment so severely in the past. There was no precedent for stopping family members from leaving,” Liu remembers.

He waited.

And waited.

And waited.

Three hours had gone past the time they were due to arrive. And his wife wasn’t answering her phone. Station staff told him there were no delays and that was it for the night – there were no more trains.

That’s when he knew for sure something was wrong.

His family had been put under an exit ban to punish him.

Police board the train

Over the border in China, Lu Lina and her son had successfully boarded their train in Guangzhou.

When it stopped at a station in Shenzhen, just across the border from Hong Kong, she saw a group of police officers get onto the train and start walking down the aisle towards them.

“I kind of suspected they were looking for me,” she says. “I didn’t know what to do. I felt so helpless when I thought that I might never be able to see my husband again.”

The police confiscated her phone, grabbed her luggage and bundled them off the train and into a car. Frightened, her little boy started crying.

Lu was held incommunicado for three days in a secret detention system called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL).

Three years apart

The next three years were tough.

In Hong Kong, Liu was devastated. He knew that if he returned to China, the police would immediately detain him and he wouldn’t be able to help his family if he was behind bars.

“I knew I couldn’t go back to China, so my only choice was to go to the US.”

In China, Lu was forced to move house and their son was turned away from several schools.

“In the beginning, I felt hopeless,” she says. “I felt we would never be together as a family again. I was also very worried about our son never being able to go to school again. It was such a stressful time.”

Meanwhile, Liu had made a life for himself in the US and found work. Every day husband and wife would speak via video call, and try to support each other.

“It was very difficult,” remembers Liu. “And after three years I felt the separation from my son very keenly. We felt extremely troubled but we didn’t have any other choice. We just had to deal with it.”

Lu made three other attempts to leave China in those three years. She tried Hong Kong again, then Macau and lastly she attempted to fly from Chengdu.

Each time, the border officials blocked them.

“They didn’t give me any documents to explain why; they just said according to this and this Article of the law, you are forbidden from leaving China,” says Lu. “Informally, they told us it was because of my husband.”

Getting divorced to be together

After two years of being apart, they came up with an idea.

What if they got divorced? Would the CCP lift the collective punishment from Lu and their son?

“My wife and child were being punished because of me… After two years we thought about dissolving our legal relationship to see if that would help. So through video call, we legally got divorced.”

Court hearings in China can legally be held using video links, including granting divorces.

Ten months after the divorce, in October 2022, Lu was told her exit ban would be lifted.

Family reunited

In December 2022, Lu and their son finally began their journey to the US.

First stop was Macau.

“I felt very anxious as I passed the border,” she remembers. “It was truly unbelievable that I could make it to Macau. I thought they might capture me and take me back.”

From Macau, they flew to Taipei and then onto the US.

“I finally felt free,” she says. “I had escaped the oppression of the CCP.”

Liu was waiting for them at the airport.

“I was extremely happy and excited. When my wife and child were in front of me, I couldn't believe it was real. After so many years of separation, that moment felt like a dream, very surreal. It wasn't until a few months later that I realized it wasn't a dream; it was real.”

And free from the CCP’s collective punishment, Liu and Lina happily got remarried in the US.

The story of Liu Sifang and Lu Lina show just how bad the problem of the CCP’s collective punishment is today in China. And how desperate people are to escape such injustices.

There are thousands of other stories that do not have such a happy ending. Some of them are told in our latest report Families in Fear (download full report here, or the executive summary here).

Although they are now reunited in the US, Liu and Lu have not forgotten all the other families of rights defenders who are victims of the CCP’s collective punishment.

“We can feel their pain, we have experienced the same pain,” says Liu. “Please stay strong and take care.”