PRC ends cooperation on illegal immigration - exposé shows there was little to end

In so-called retaliation for US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei, the People’s Republic of China has rapidly escalated its “counteractions”. Beyond the evident escalation in military drills and the imposition of individual sanctions on Speaker Pelosi and family members, Beijing also announced the suspension of eight specific areas of cooperation with the U.S.

Of those areas – presented as below by the CCP’s English-language mouthpiece Global Times – no less than three are directly linked to international legal cooperation (e.g., points four, five and six). Of particular interest is the announced suspension on cooperation on illegal immigration, potentially affecting nearly 40,000 Chinese nationals currently living in the U.S. illegally and pending repatriation to China[1]. In Canada, Chinese illegal immigrants top the “removal inventory” of those to be repatriated[2].

It will also show how China has consistently used the issue of vast numbers of Chinese illegal immigrants in those countries as a tool of leverage to try to force the return of politically sensitive targets instead, while seemingly having no interest in the return of illegal immigrants at all.

It has become exceedingly clear over the years that China is seeking what can best be described as selective international judicial cooperation with the same aim of forcing the return of politically sensitive targets. There is some irony in China’s announced unilateral suspension, as it stands in strong contrast to its usual indignant lambasting of countries refusing for example to sign on to a bilateral extradition treaty. Prone to the accusation that failure to ratify extradition treaties with China - or otherwise assist in returning people they claim are fugitives to China - as creating “safe havens” for “criminals”[3], many countries have stepped into the trap, yet Australia, Canada, the UK and the U.S. are among the few to resist Beijing’s syren call on the matter.

That has not stopped the CCP from further actions: it has repeatedly threatened that if extradition treaties are not ratified, China has no choice but to engage in “alternative methods”. When Australia failed to ratify a long-in-development treaty, the director of Peking University's anti-corruption study centre, Zhuang Deshui, said the extradition treaty was but one way for China to return fugitives and recover stolen funds. "When this gate is not open, we can try the window, and if windows are not open, we can try digging holes."[4]

Against this backdrop, the cancellation of several forms of judicial cooperation with the U.S. - including on illegal immigration - rather than a surprise is but a confirmation of the fact that China’s interests lay not in actual loyal and reciprocal cooperation, but in securing the return of their priority targets. The latter objective increasingly under pressure - given the growing scrutiny of their atrocious human rights record inside the PRC and on the use of illegal methods when operating against individuals abroad -, China’s authorities seem all too willing to drop the pretence.

Also see: Switzerland’s secret cooperation with Chinese police

The U.S.’s troubled past on cooperation on repatriation of illegal immigrants with China

In the U.S., officials have for many years sought Chinese cooperation to deal with the increasing number of illegal immigrants. As of 2021, the removal inventory of illegal Chinese immigrants, stood at 39,000 people.

What does illegal immigrant repatriation mean? The U.S. – as any other country in the world - is unable to repatriate illegal immigrants if they do not have valid travel documents, such as a Chinese passport. Legally, there is simply no way to put someone on a flight to China without such documentation and the only entity able to produce such documents is the Chinese government - specifically the Exit and Entry administration under the Ministry of Public Security (MPS). For long periods, both the U.S. and Canada – as well as other countries, such as Switzerland[5] - have sought to get such cooperation from China in an effort to relieve the burden of hosting illegal immigrants.

The problem?

China knows of this burden and will not cooperate unless if gets something in return. After all, there are no Canadian, U.S. or Swiss illegal immigrants in China, at least not in any real numbers. China has used this asymmetry as a tool of leverage: in return, they want their counterparts to return people sought after by the Chinese police.

A Memorandum of Understanding between the Chinese MPS and U.S.’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) signed prior to the State visit in early 2015 was supposed to expedite the process. The U.S. started rounding up many of the illegal immigrants, expecting a round of repatriation that never arrived. In the end, the immigrants were released from detention and most remain in the U.S. to this day.[6]

As reported by Reuters, “China has been extremely slow, U.S. immigration officials say, to provide the proof of citizenship necessary to send visa violators home. Some of the nearly 39,000 Chinese immigrants awaiting deportation have been under orders to leave for well over a decade, and the backlog continues to grow. 900 of them classed as violent offenders, according to immigration officials.” The explanation from one U.S. official was simple: “They do not want these people back.”[7]

It became clear China would not assist in this unless the U.S. side also “threw in” some of the names on the CCP’s Fox Hunt target list – many of whom were legal residents in the U.S. At the time, the “wanted” list presented by China numbered some 200 people[8].

Acting in accordance with national and international law, the U.S. refused the bargain. It was revealed later that during these very negotiations - tied to a high profile meeting between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping in Washington - China’s Fox Hunt campaign had been carrying out undercover and highly illegal operations to have some of these targets returned against their will via coercion, intimidation and harassment.[9] These operations continue to date, and as recent as May 2022 a new slew of agents were indicted.

Liu Dong, director of Fox Hunt said: “Our principle is thus: Whether or not there is an agreement in place, as long as there is information that there is a criminal suspect, we will chase them over there, we will take our work to them, anywhere.”[10]

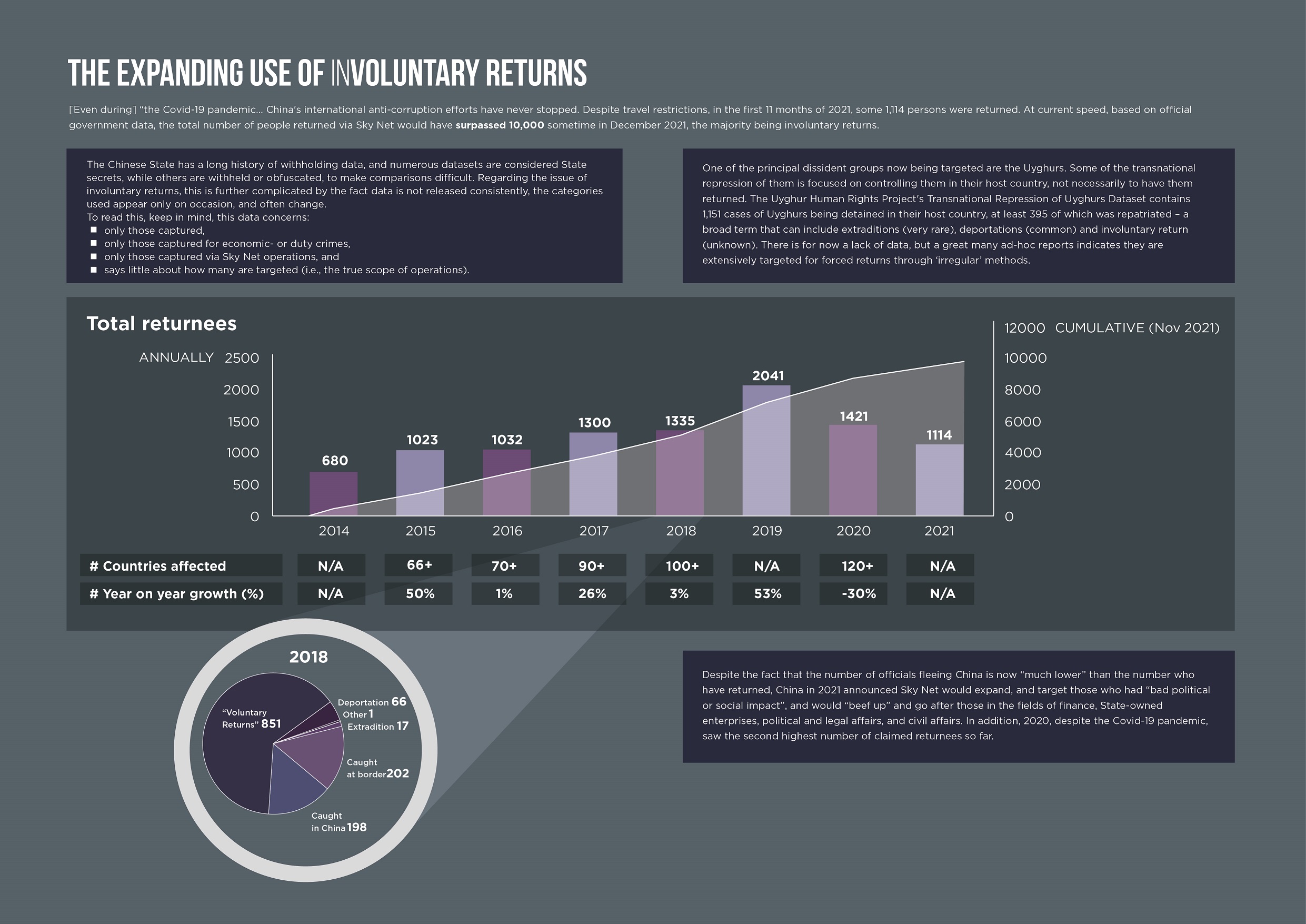

Fox Hunt is the Chinese police-run campaign, launched in 2014, to seek the return of claimed economic fugitives outside of China. The larger Sky Net operation, which controls Fox Hunt, is run by the National Supervision Commission (NSC), and complements Fox Hunt with a number of different components, coordinating a great many government bodies’ work on the subject. For details, see Safeguard Defenders report Involuntary Returns. Only those accused of economic crimes are officially accounted for in public reports on Sky Net operations, which by Christmas 2021 surpassed 10,000 successful returns, most via illegal means, while others - the vast majority - are not included in these statistics. The program has continued unabated during the COVID pandemic, and in 2022 it was announced it would expand further.

Canada: Placing legal Chinese residents at risk to secure Chinese cooperation

The situation in Canada is similar. Thanks to the wealth of information secured via a Freedom of Information request by The Globe and Mail reporter Nathan Vander Klippe and later by Safeguard Defenders, we can gain further insight into how China is using the repatriation of illegal immigrants as a bargaining chip to instead try to expand its global policing power and reach those wanted by China abroad. We can also see how Chinese authorities have been far more helpful - at least for certain time periods - in assisting the repatriation of illegal immigrants, and how the Canadian government has provided extensive help in return, placing many Chinese nationals living legally in Canada under threat from the Chinese police.

Canada had started negotiations with China on the development of an agreement to repatriate illegal immigrants (‘readmission arrangement’) in 2011. China consistently refused to sign such an agreement unless it was accompanied by a sweeping extradition treaty. By 2014, Canada has some 2,143 Chinese nationals on their ‘removal inventory’ list – with little change up to 2021, with 1,857 awaiting removal. Between 2008 and 2020, between 300 and 800 people were repatriated each year, for a total of 6,597 Chinese nationals sent back during that period.[11] Of those 6,597 people, only 332 were sent back because Canada had ‘safety and security’ concerns about the individuals or because they had committed crimes in Canada.[12]

While Canada wanted to have all the illegals repatriated, during the negotiations China was instead exclusively focused on securing the return of some 150 specific targets - all wanted under its Fox Hunt operations – without having to follow formal extradition proceedings and in the absence of a bilateral extradition treaty with Canada.

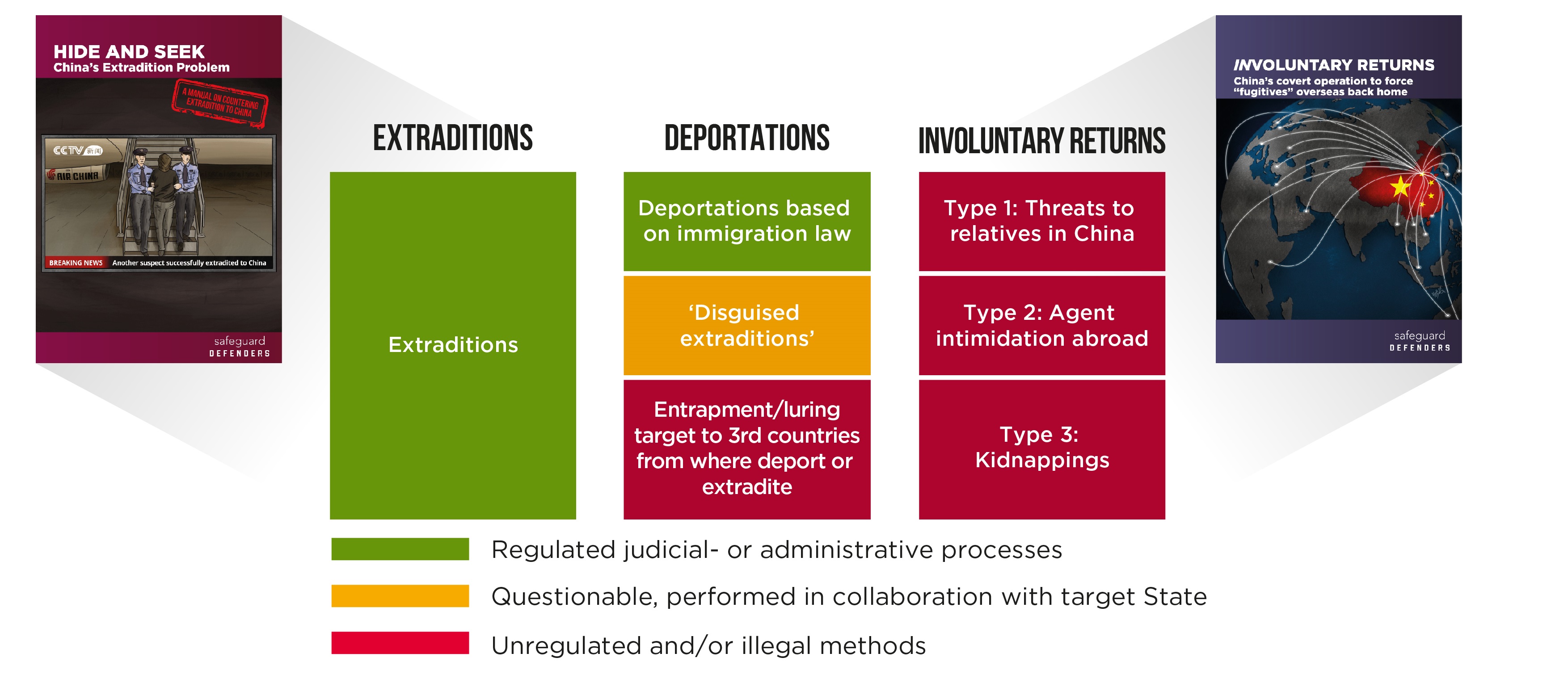

For more on Chinese long-arm policing, and its different methods, see the two reports Hide and Seek (Returned Without Rights for shorter version) and Involuntary Returns.

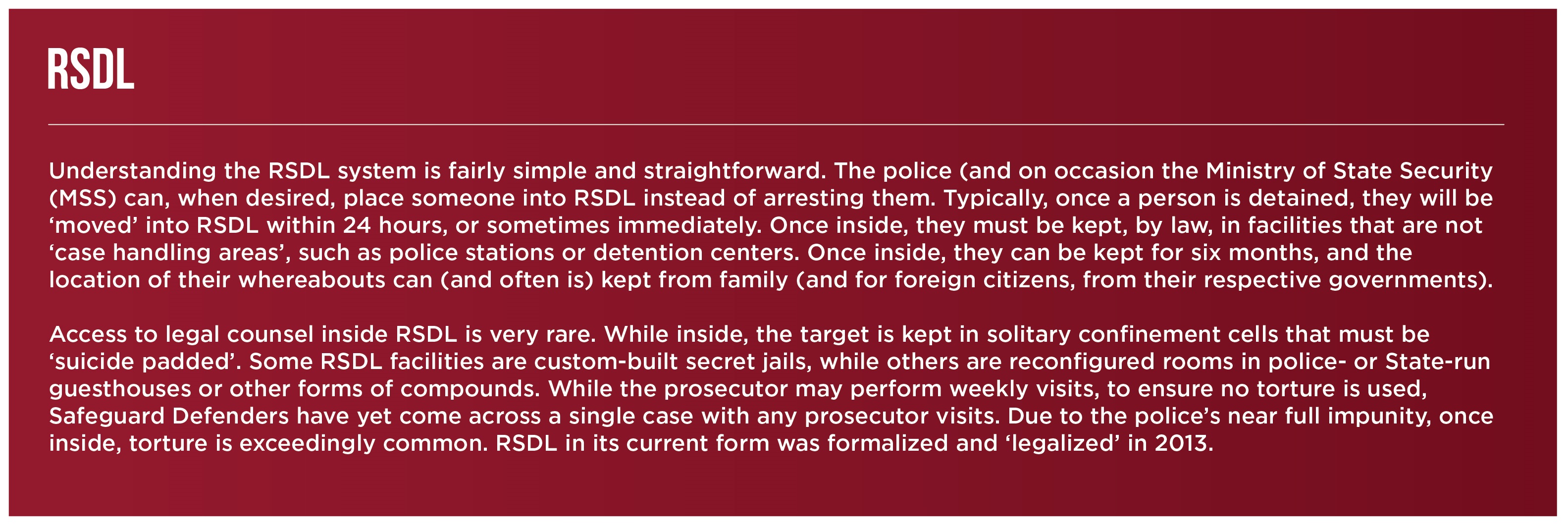

One reporter specialized in covering parliamentary proceedings and the government made clear that Canada had to pretend to be willing to entertain the development of an extradition treaty simply because China in 2014 took two Canadians hostage. Kevin- and Julia Garratt, a couple running a coffee shop in the China-North Korea border town of Dandong, had both been placed into China’s fear RSDL system – essentially secret detention at an unknown location and kept incommunicado in solitary confinement.

It would take almost two years to secure their release. It is believed that the detention and disappearance of the two Garratts was a direct response to Canada’s arrest of a Chinese spy, in a tale that echoes the more recent hostage taking and diplomacy surrounding Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor. After the Garratt’s release, the development of the potential bilateral extradition treaty was abandoned[13][14], confirming the above journalist’s assumption that ongoing negotiations were indeed directly tied to China’s hostage diplomacy.

However, by autumn of 2016 Canada signed a Memorandum of Understanding with China on law enforcement cooperation, essentially - and knowingly - assisting China’s Fox Hunt operation on Canadian soil, and indicating that it would negotiate a potential extradition treaty.[15][16] Between 2014 and early 2017, an additional 1,386 where repatriated to China.[17]

So how did Canada manage to - at least temporarily - secure the cooperation of China to return illegal immigrants? According to documentation from the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), it enthusiastically agreed to or even encouraged the establishment of mechanisms for the Chinese police to use its embassy and consulates to expand its Fox Hunt operations in Canada, and allowing the Chinese police to engage in “persuasion to return” activities targeting Chinese living in Canada, including legal residents.

These methods have been closely studied by Safeguard Defenders in its ground-breaking report Involuntary Returns, where “persuasion to return” activities are referred to as Involuntary Return type 1. In these cases, Chinese police either threatens, harass, detains or imprisons relatives back in China, or threatens to do so, unless the wanted person returns “voluntarily”. This is carried out on mass-scale, numbering thousands of people every year.

In this case, Canada supported a further violation, namely type 2 operations, where agents or representatives are sent to the target’s country of residence - in this case Canada - to engage with them directly on foreign soil. The document goes further to claim that regular removal proceedings against many Chinese nationals are extra difficult because some “seem to have unlimited resources to delay removal”.

In fact, CBSA documents refer to such “persuasion to return” practices as a “best practice”, seemingly unaware of the reality behind such operations, or perhaps wilfully turning a blind eye.

On the subject of the Chinese government's “engagement” with Chinese nationals in Canada, CBSA documents state that:

“The CBSA cannot be a party to the negotiations, however can provide support upon request from either participant:

- CBSA can alter conditions of release to allow the subject to travel to participate;

- CBSA may be able to facilitate the issuance visas for PRC officials who are coming to take part in the negotiations;

- If required, can facilitate logistics at an airport to assist with the departure”.

It gets worse.

CBSA documents state that: “The PRC embassy in Ottawa has initiated a process to engage these alleged fugitives in negotiations for the voluntary return to the PRC.” It then goes a step further, stating that “The negotiations between the PRC government and its nationals in Canada can occur concurrently with the hearing process before the IRB or with the CBSA’s removal process”. This is extraordinary, as it indicates an awareness of - and at least tacit approval - of Chinese police and government engaging in actions against a target while that target is going through a legally established Canadian immigration procedure, entirely undermining the victim or target’s right to have said procedure establish whether they have the right to stay or not.

In response to questions asked by Safeguard Defenders, the CBSA has responded they have not supported the Chinese police in having any persons removed from Canada, but as outlined above, the tacit agreement shown in these documents makes it clear that while China engages in such operations alone, the CBSA can assist in logistics for the return flight “if needed and asked”.

It is unclear what level of cooperation is still ongoing between the Canadian and Chinese governments on this issue since high-level talks stalled and the last National Security and Law Dialogue as well as Law Enforcement Working Group were held in mid- and late 2017 respectively[18].

Following Safeguard Defenders’ release of its Involuntary Returns report, Royal Canadian Mountain Police Commissioner Brenda Lucki confirmed to The Globe and Mail that “It is a growing problem, obviously, and something we want to work together with our international and domestic partners on. A lot of it is about awareness and education, because things happen and we want to make sure people who are affected by this feel safe – that they can report this without fear of reprisal.”

Moving forward

China’s continued use of the “safe haven” arguments to push foreign governments to cooperate in judicial matters or its tit-for-tat requests when it comes to illegal immigration are used exclusively with the aim of extending the Chinese police’s long-arm over Chinese nationals abroad - including legal residents - as part of its wider Fox Hunt and Sky Net campaign. China’s decision to stop cooperation with the U.S. on illegal immigration, as well as on other forms of judicial cooperation, further highlights how these cooperations are but a political tool in the PRC’s toolbox, and only ever was.

China already announced an expansion of its Sky Net operation during the national congress this March.

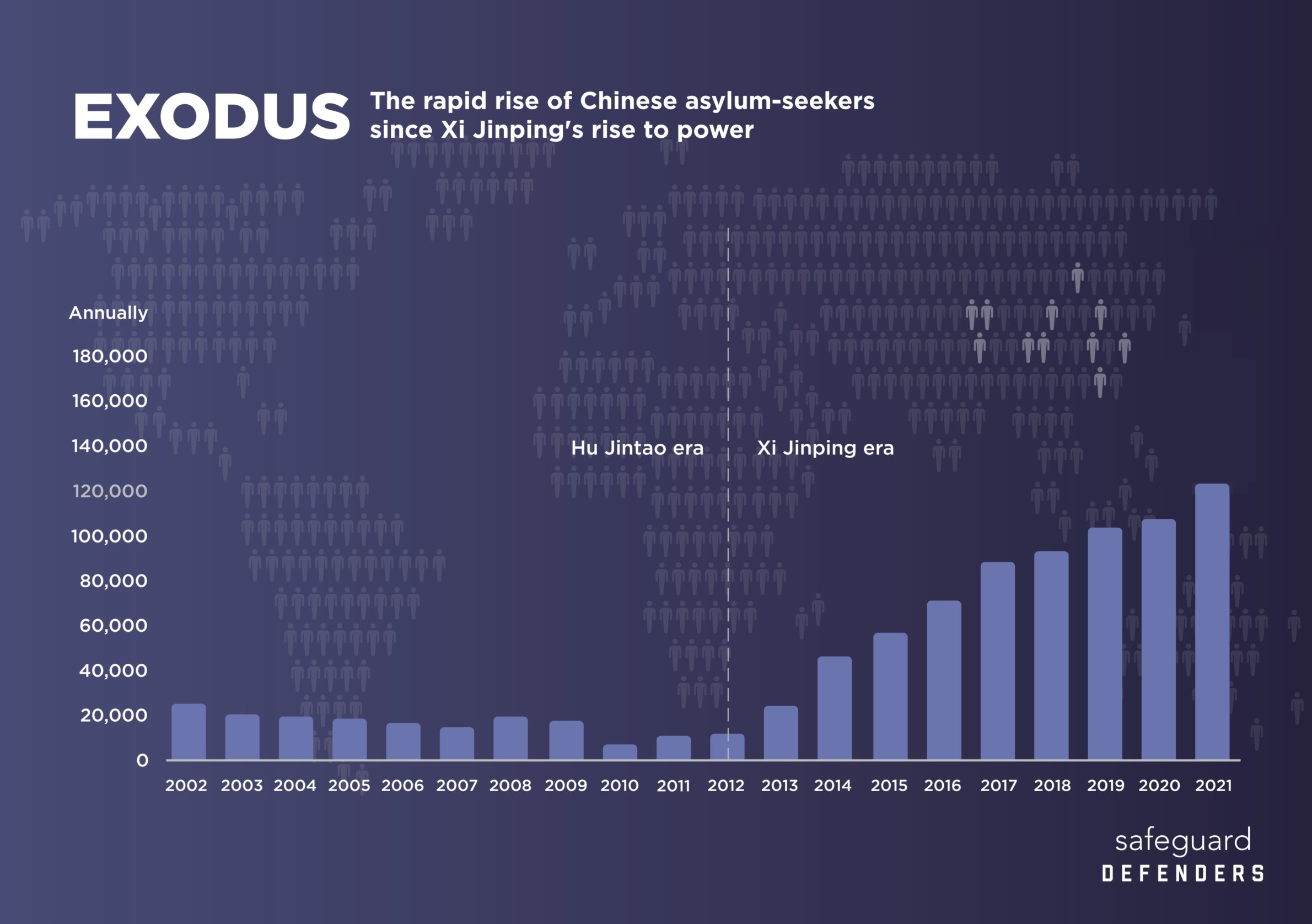

With the suspension or termination of the little cooperation that did exist, we can unfortunately expect a dedicated focus from China’s side to further engage in undercover and illegal operations abroad, whether to “persuade” people to return from afar or by directly engaging in threats and intimidation on U.S. soil. Given the rapidly expanding stream of Chinese asylum seekers, in particular in the U.S., as exposed by Safeguard Defenders, it adds further incitement for China to expand said long-arm policing. One may argue that rather than responding to Speaker Pelosi’s visit, China seized the moment to retaliate against the U.S.’s recent and most opportune counter-measures to these operations.

For more reports, investigations and news related to long-arm policing, extradition, fugitive hunting and more, see Safeguard Defenders website.

[1] https://www.propublica.org/article/operation-fox-hunt-how-china-exports-repression-using-a-network-of-spies-hidden-in-plain-sight

[2] Documentation provided by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) in response to FOI request (available per request)

[3] See for example: As for the U.S., China has made clear that the lack of an extradition treaty with the United States, they say, makes the country a “refuge for runaway criminals” - https://www.propublica.org/article/operation-fox-hunt-how-china-exports-repression-using-a-network-of-spies-hidden-in-plain-sight.

[4] https://www.smh.com.au/world/china-will-use-other-options-to-return-fugitives-as-extradition-treaty-falters-20170330-gv9ztr.html

[5] Switzerland’s secret cooperation with Chinese police. Just before Christmas 2020, Safeguard Defenders exposed that the Swiss government had entered into an unpublished agreement with the Chinese police on the repatriation of illegal immigrants[5]. At first sight, it might appear that China was sincere in its offer to assist in repatriating such illegal immigrants. However, as the Swiss government entered damage control mode after world media reported on Safeguard Defenders’ exposé, it became clear that was not actually the case. The agreement allowed for Chinese police to provide unvetted officials with tourist visas for Switzerland, allowing them unregistered and unsupervised access to not only Switzerland, but the entire Schengen area. No Schengen governments were made aware of this agreement. As the deal was to be renewed, the Swiss government responded to Safeguard Defenders saying that it was the Swiss side that had sought the agreement, and that only one trip was made during the five-year period[5]. Among nearly 60 such agreements with governments around the world, it was the only one kept from the public. The Swiss never managed to fully explain why, offering only easily seen through excuses. In the end, China rarely chose to use it and after the media storm that followed, the deal was not – as first planned – renewed upon expiry.

For more background see: https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/blog/lies-and-spies-switzerland-s-secret-deal-chinese-police and https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/blog/switzerland-answers-some-and-dodges-other-questions-its-secret-china-deal.

[6] https://www.reuters.com/article/ususa-china-deportations-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-to-china-take-back-your-undocumentedimmigrants-idUSKCN0RB0D020150911

[7] https://www.reuters.com/article/ususa-china-deportations-exclusive/exclusive-u-s-to-china-take-back-your-undocumentedimmigrants-idUSKCN0RB0D020150911

[9] https://www.propublica.org/article/operation-fox-hunt-how-china-exports-repression-using-a-network-of-spies-hidden-in-plain-sight

[10] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/17/us/politics/obama-administration-warns-beijing-about-agents-operating-in-us.html

[11] Based on information ascertained by Safeguard Defenders from the CBSA via Freedom of Information request.

[12] Based on information ascertained by Safeguard Defenders from the CBSA via Freedom of Information request.

[14] https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/backgrounders/2016/09/13/joint-communique-1st-canada-china-high-level-national-security-and

[16] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/21/world/americas/canada-agrees-to-talks-with-china-on-extradition.html

[17] https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/canada-deports-hundreds-to-china-each-year-with-no-treatment-guarantee/article34558610/

[18] https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/publications/transparency-transparence/briefing-documents-information/parl_appearances-comparutions_parl-cacn-2020-01-30.aspx?lang=eng#a3_11