Shining a light onto the abuses of the Chinese state

6 December 2017 - The main driving force behind this new book of first-person stories of China’s state-sanctioned kidnappings is Michael Caster, a US human rights advocate and researcher. While Michael himself was never detained, he used to work with Swedish rights activist Peter Dahlin, whose own story of abuse under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) is detailed in Chapter 5 in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared. The two men ran a legal aid NGO called China Action from Beijing, which helped provide funding and logistical support for barefoot lawyers. Here Michael explains why he thinks it is so important for this book to be made now and why we should all start caring about this new chilling tool of abuse.

6 December 2017 - The main driving force behind this new book of first-person stories of China’s state-sanctioned kidnappings is Michael Caster, a US human rights advocate and researcher. While Michael himself was never detained, he used to work with Swedish rights activist Peter Dahlin, whose own story of abuse under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) is detailed in Chapter 5 in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared. The two men ran a legal aid NGO called China Action from Beijing, which helped provide funding and logistical support for barefoot lawyers. Here Michael explains why he thinks it is so important for this book to be made now and why we should all start caring about this new chilling tool of abuse.

Q: You were the main driving force behind this book. Can you explain why The People’s Republic of the Disappeared was written and published now? The driving force was to help the world see that RSDL is far from a softer form of detention but another piece in China’s totalitarian apparatus of terror and control.

Q: The people who volunteered their stories for The People’s Republic of the Disappeared did so at considerable risk to themselves. Can you tell us why you think they agreed in the end?

At the end of her chapter, (human rights lawyer) Wang Yu writes:

I have often wanted to write about my experiences. But so often, after picking up my pen, I found myself just putting it down again. I always felt that they were memories hard to look back upon, but that if I didn’t record them in time, eventually they would fade away. So I forced myself to write this time.

These stories are about memorialization, about providing testimony against the abuses perpetrated by the Chinese government against its own people. And they are about healing. Those who agreed to share their stories are people who have already made great sacrifices as rights defenders, and in agreeing to share their stories they have continued to make sacrifices for others. These stories provide great context for international condemnation and advocacy, in that by showing the systematic nature of abuses they fuel international pressure for China to abolish RSDL. But, they also provide some guidance, some insight for those rights defenders who still might find themselves picked up and disappeared into the RSDL system. And in that sense they offer some degree of protection.

Q: The people in this book are human rights defenders – lawyers, activists and so on. What kinds of things do they do that make the authorities put them into RSDL? In an authoritarian system, the law exists, where it exists at all, to protect and further the interests of the Party. What these rights defenders have done to end up inside RSDL is merely to have attempted to work within the confines of the law to protect the rights of Chinese citizens.

"Under international law there are no circumstances that permit for enforced disappearances, and yet that is exactly what China has done with RSDL." [Michael Caster].

Q: Who is RSDL targeted at? And roughly since 2013 how many people have been subjected to this chilling practice? In principle, RSDL is reserved for crimes related to endangering national security, involving terrorist activities, or those involving significant bribes. The stories of RSDL in this book show that it is clearly being used to target the human rights community. It is a calculated tool of repression. I think what is more important to emphasize than the total number of people to have passed through RSDL is the systematic nature of RSDL. Especially in these stories, we see a certain predictability of suffering, in both means and consequences. It is not as much a matter of how many people have been subjected to this chilling practice, but the cold, calculated, planning behind its legislation and implementation.

Q: China legalized RSDL in 2013. Can you briefly explain why you think it did this? For more than a decade, China has been experimenting with administrative, criminal, and extrajudicial procedures to remove, silence, detain, imprison, and disappear regime opponents, from the Custody and Repatriation system of the early 2000s or the use of Black Jails that followed. Effectively RSDL represents China’s effort to mask enforced disappearances behind the veneer of the rule of law.

Q: Before it was legalized, China’s enforced disappearances still took place in Black Jails and other locations. Why is RSDL worse than this situation? Black Jails were an extrajudicial system for detaining and disappearing regime opponents. They existed purely in the shadows. But RSDL is worse in that it represents the efforts of the state to legalize the impermissible. Under international law there are no circumstances that permit for enforced disappearances, and yet that is exactly what China has done with RSDL.

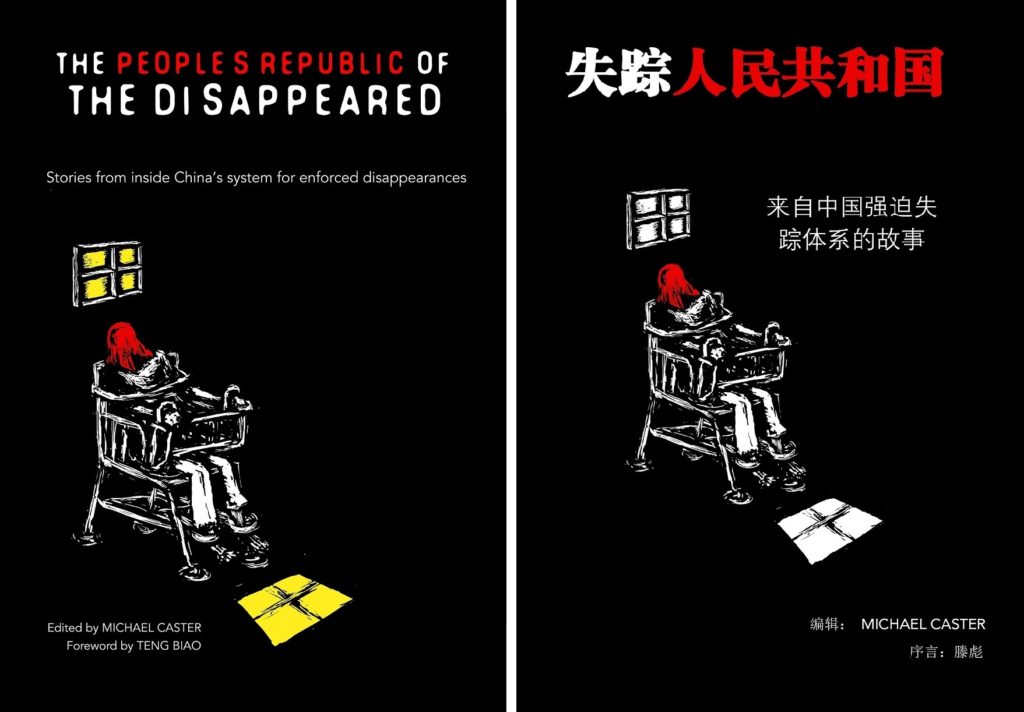

English and Chinese versions of The People's Republic of the Disappeared.

English and Chinese versions of The People's Republic of the Disappeared.

Q: At the 19th Party Congress in late 2017, president Xi Jinping said he would scrap the secret internal disciplinary system of shuanggui – a kind of RSDL for Party members. Does that give you any hope that RSDL will be abandoned? No. As we have seen many times before, when one system of abuse is abandoned another simply comes in its place. Even if Shuanggui is scrapped, something else will rise in its place. And as for RSDL, the vocabulary in the National Human Rights Action Plan (2016-2020), and the noted expansion of facilities dedicated to RSDL, indicate there is little intention to slow the use of RSDL in Xi Jinping’s second term.

Q: Some people may argue while enforced disappearances appears repugnant to many outside China, it is a legal custodial system under Chinese law and there is not a lot we can do about it. On what legal basis can other countries and international bodies urge Beijing to change? Slavery was legal in the United States long after it had been criminalized by much of the rest of the world. Apartheid was legal in South Africa and yet the world galvanized in opposition to its repulsiveness. Slavery, torture, enforced disappearances, these are considered so vile that they are an insult to humanity at large. There is a universal obligation to speak out against them, and in some circumstances a universal obligation to intervene. This is all the more pressing in cases where torture has taken place, and torture is certainly systematic within RSDL.

Q: What do you hope that this book will achieve? I hope this book will shine a light onto the abuses of the Chinese state, and encourage more people around the world to demand action from their leaders in holding the Chinese state accountable to its flagrant violations of human rights law and cruelty toward its people. The point of this book was to provide a thorough picture of what it means to disappear in China because frankly too many people were still unaware or indifferent to what RSDL actually represented.