Anatomy of a legal farce - first journalist imprisoned for reporting on Covid19 virus in China

China has handed down the first prison sentence to a citizen journalist for reporting on its handling of Covid-19 from Wuhan, the city where it all started. Zhang Zhan, a former lawyer from Shanghai who gained notoriety for her independent reports from Wuhan, was given four years for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” on 28 December.

But Zhang is just one of several citizen journalists who are being punished for speaking in public about the Covid-19 virus and the government's response, including others that Safeguard Defenders have reported on such as a former state media journalist. They’ve either been disappeared or arrested for their work, some paraded in videoed confessions.

With many more to go on trial on the same charge – picking quarrels and provoking trouble - we took a closer look at her case, including details of her trial, to spot clues as to what China likely has in store for the other “free-speech Covid criminals” that also dared to speak the truth.

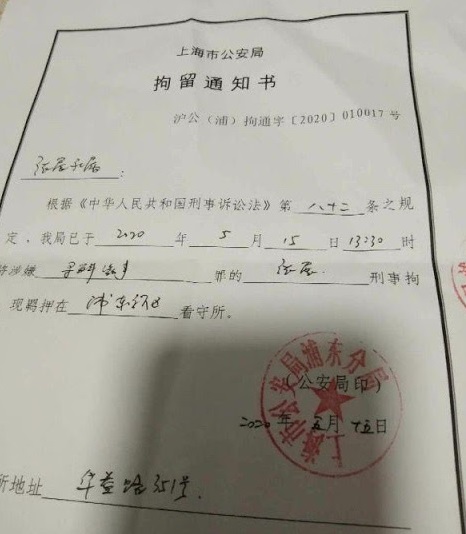

Detention and arrest

Zhang was first detained in Wuhan by local police on 14 May. She was transferred the next day to Shanghai and detained by Shanghai Pudong Police (PSB) at 13.30 on 15 May. From that time until her trial she was held at Shanghai Pudong New District Detention Centre.

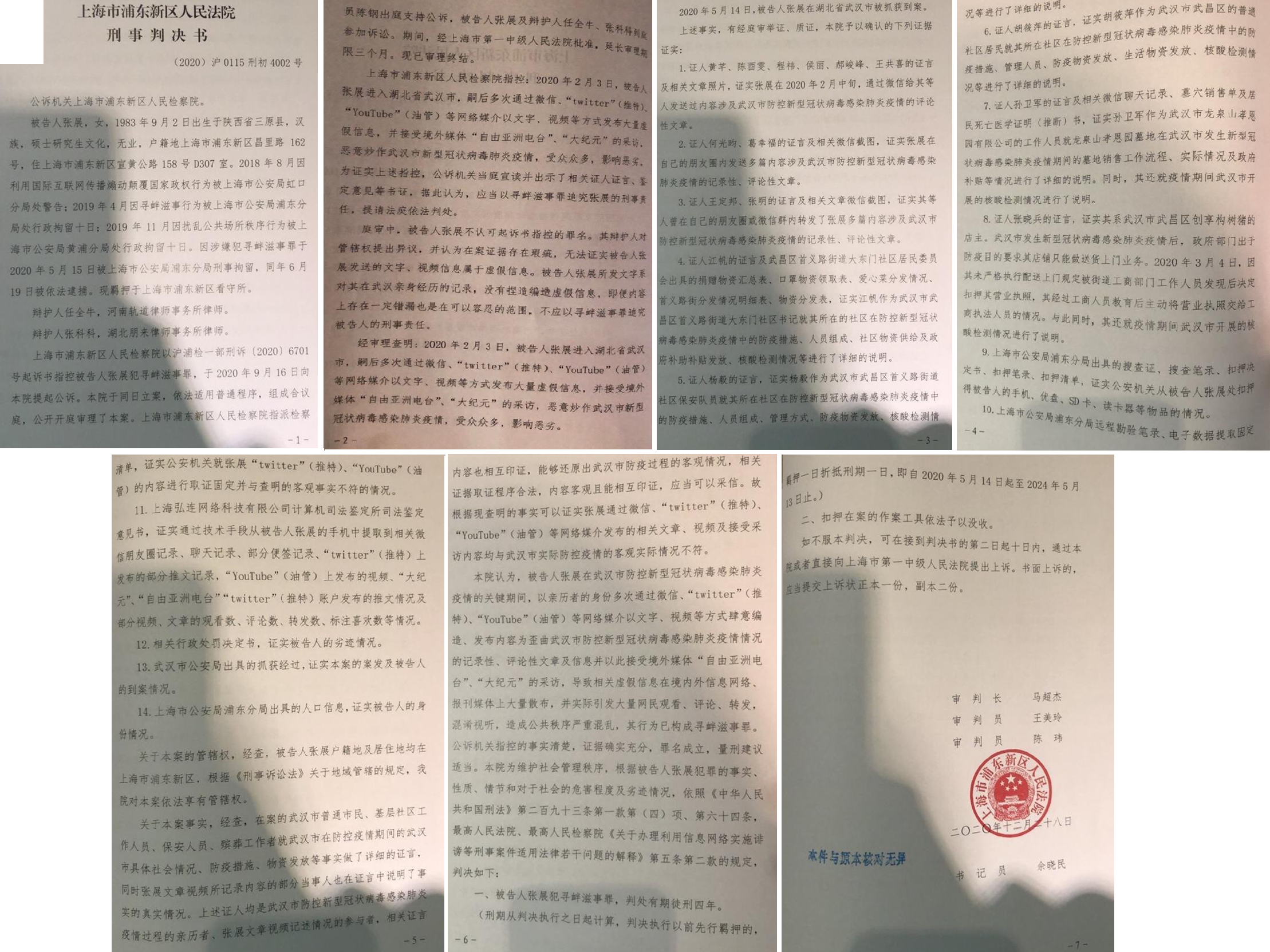

The case advanced fairly swiftly after that. With her formal arrest on 19 June, prosecution was filed for on 15 September, and her indictment made public on 13 November on public order charges of ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’ (article 293 of the Criminal Law). Just over a month later on 28 December, her trial, which took just two hours, took place at the Shanghai Pudong New Area People’s Court. At midday that day she was given a four-year prison sentence. It was no coincidence that her trial took place during the Christmas season – a favoured time to “hide” controversial court cases in the hope that western media will be distracted by the holiday.

The past decade has seen a surge in convictions for merely posting a few words on the Internet. Lawyers, journalists and NGO workers are ending up in jail, sometimes for placing just a few posts online. Human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang received a three-year suspended sentence in 2015, simply for a couple of Twitter posts, a platform banned in China. It’s worthwhile examining Zhang’s court trial more closely to see on what spurious grounds the authorities argued she should be punished.

What did Zhang do in Wuhan?

To get a taste of the kinds of things Zhang was reporting on here are two overseas media that interviewed her.

A week and a half after the Wuhan government lifted the lockdown, RFA published an interview with Zhang, who had been posting her reporting on YouTube, Twitter and Chinese social media (all this has now been deleted). The report contained these quotes from Zhang (our translation):

“The Wuhan government has indicated that the number of new Covid-19 cases are 0 for the last two days (15 and 16 April), [but] Zhang Zhan told RFA, “I went to hospital yesterday and a guard in the fever clinic told me that there were new patients on 15th.”

Zhang Zhan went to many hospitals and found that there are several hundred Covid-19 patients still in hospitals.

And:

“…many factories do not have the capacity to restart work, but they have started the machinery and are not manufacturing any products to comply with orders from officials.”

A few weeks later, The Epoch Times interviewed Zhang as part of its reporting on Wuhan and the virus pandemic:

“…after the lockdown was lifted, the quality of life for people in Wuhan was reduced because of high prices.”

Zhang Zhan was told by some volunteers that she met that there were at least 100,000 n people who died from Covid-19 in Wuhan.

“Sin is hidden in this number”.

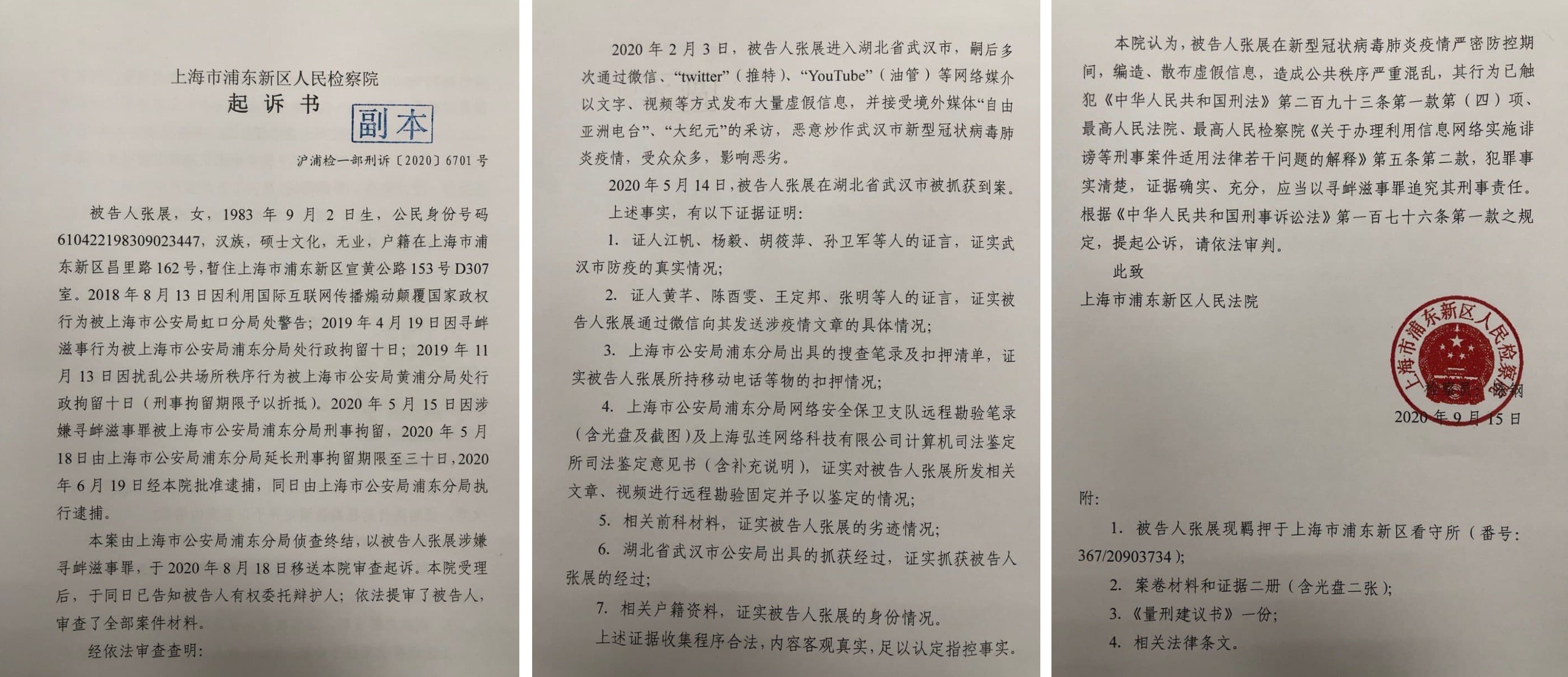

The indictment.

The trial

The indictment against her stated that Zhang had spread “false information through text, video and other media through the internet media such as WeChat, Twitter and YouTube” and “accepted interviews from overseas media Radio Free Asia and The Epoch Times and maliciously speculated on Wuhan’s Covid-19 epidemic.” As such she had violated paragraph four of Article 293 of the Criminal Law.

The lead and fourth paragraph of Article 293, often referred to as ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’, states:

Whoever undermines public order with any of the following provocative and disturbing behaviours is to be sentenced to not more than five years of fixed-term imprisonment, criminal detention, or control:

(4) creating a disturbance in a public place, causing serious disorder.

The prosecution, led by Chen Gang, accused Zhang of entering Wuhan on 3 February and using her social media and giving interviews to overseas to “maliciously hype’ the pandemic to large audiences.

Source: The Guardian

The evidence included information proving her ownership of the social media she used to share information and a long list of witnesses, none of which however appeared in court. Some of these witnesses admitted to reposting or forwarding Zhang’s articles and posts. Other witnesses were brought out to dispute Zhang’s claims in her reporting. But these witnesses did not give their evidence in court, the prosecutor simply read their statements and showed screenshots supplied by them meaning that the defence had no opportunity to cross-examine any of them.

- Six witnesses provided testimony and images showing that Zhang had sent them her opinion posts on the outbreak in Wuhan over Wechat in mid-February.

- Two others provided screenshots from WeChat messages showing Zhang’s posts of opinion pieces on the outbreak on her WeChat “moments”.

- Two witnesses provided evidence they had forwarded some of the articles Zhang had written and/or posted on her WeChat.

- Other witnesses ranging from a security guard of a residential compound, the owner of a butcher shop and a cemetery worker, gave statements to dispute the details of Zhang’s reports. Some of these disputed comments were made by people Zhang had interviewed and then reported, not actual statements made by Zhang herself.

Many of the witness statements are about other people responding, or in this case, forwarding or sharing, Zhang Zhan’s opinions to friends online. Furthermore, the interviews given to foreign media were not accessible to Chinese people, nor where her videos posted on YouTube or her commentary on Twitter, as they are all blocked in China. Neither those media, nor her Twitter or YouTube channels, have a significant readership that could, or have, caused any public confusion in China.

Zhang’s lawyers said she pleaded “not guilty” to the charge and argued that the case and evidence were flawed. She had, they said, only expressed what she had seen and that there was no evidence that she had fabricated anything. Zhang argued that all the materials she gathered and reported on were first-hand accounts and that she had not fabricated any information. The fact that her lawyers could not cross-examine any of the witnesses meant they had no chance to disprove the allegations.

Source: Arab News

The lawyers’ request to have the witnesses appear in court was denied, dooming any ability to counter the prosecution's accusations, as no cross-examination was possible. Likewise, all other requests by her legal defence were denied, including their application for extension of court time, application for bail, application for live streaming of the trial, and request for videos to be played in court, and interviews conducted with witnesses by the police to be presented – instead of merely having the prosecutor read out their [claimed] statements.

Her lawyers went on to argue that Zhang had merely published her opinions as a private citizen and offered her opinions in interviews to the media. Indeed, even the prosecution said, and used witnesses, to reinforce these facts. These two acts, her lawyers said, were clearly not crimes. They also did not qualify as spreading false information because they were her opinions, irrespective of whether she was inaccurate or not.

The judges concluded that (our translation):

“During the critical period of Wuhan's prevention and control of the new Coronavirus epidemic, Zhang Zhan, in her capacity as a witness, repeatedly fabricated and published documentary and commentary articles and information that distorted the situation of Wuhan's prevention and control of the epidemic, by means of text and video through WeChat, Twitter, YouTube and other online media, and through interviews given to overseas media Radio Free Asia and The Epoch Times.

"This led to the spreading of the false information on domestic and foreign information networks and newspapers and media, and caused a large number of netizens to watch, comment and forward the information, confusing the public and causing public disorder.”

The verdict.

Zhang’s condition

Unusually Zhang appeared to have been able to appoint her own lawyers – in many cases like this, the victim is usually forced to dismiss their own legal counsel and accept state-appointed lawyers. One of her lawyers, Zhang Keke said that she was being force-fed via a feeding tube – Zhang had gone on hunger strike to protest her detention months earlier. She was suffering from headaches, dizziness and stomach pain. He told the BBC: "Restrained 24 hours a day, she needs assistance going to the bathroom, and she tosses and turns in her sleep… She feels psychologically exhausted, like every day is a torment."

Her other lawyer, Ren Quanniu, also expressed fears for her health, saying she was very weak.

Zhang herself attended her trial in a wheelchair and spoke faintly, looking very ill. But she still found strength to argue with the judge. But as legal scholar Jerome Cohen wrote in the SCMP on January 3, “Indeed, we do not know whether Zhang was so weak that she could not possibly take meaningful part in a trial”.

Ren said Zhang "looked devastated" when her sentence was announced in court, and that her mother sobbed loudly.

Zhang Zhan is set to serve in prison until May 13, 2024.

State media's response

Following her verdict on February 28, Global Times posted a video report, and also an editorial by Hu Xijin, both the very next day, desperately trying to defend the sentencing of her, which had been scheduled for Christmas to try to avoid attention. Hu also refers to her as operating under delusions. He also says that her reporting, using ‘micro perspectives’ (people’s own accounts) are not lies or fabrications, but ‘disconnected’ from the true context, and goes on to say that maybe what she reported was indeed what she saw and heard.

Hu and the Global Times manages to undermine the court’s verdict and the entire argument for her conviction, namely that she intentionally fabricated falsehoods. The Global Times articles does however bring us closer to the truth, namely that “Her behavior is in conflict with China's social governance system, seemingly the real reason for her conviction.

Chinese-language State/Party media has remained quiet about her trial.

The others

Chen Mei, an NGO worker, Cai Wei, a tech company worker, and his girlfriend Xiao Tang, stored news articles about the coronavirus on a Github repository. These were news articles that Chinese censors were scrubbing off the Internet. They were all disappeared into RSDL (a secret incommunicado detention that has no judicial oversight). Chen and Cai are now charged with the same crime as Zhang.

Activist Xie Fengxia and retired Professor Chen Zhaozhi have likewise been arrested on the same charge, while former Professor Guo Quan is being held under the more serious charge of inciting subversion of state power.

Citizen journalists Fang Bin, Chen Qiushi, and Li Zehua were disappeared for prolonged periods, and some of them are still missing. Li reappeared in a dubious video that resembled a forced confession. Others, like Professor Xu Zhangrun disappeared after penning articles online, only to be placed under house arrest.