Australian journalist falls victim to China's hostage diplomacy

The latest victim of China's hostage diplomacy, in a very long line of victims, is Australian citizen Cheng Lei (pictured, photo from her Facebook page). She has been working for China's Party-state TV station CGTN for eight years and is a high-profile anchor of their Global Business show. Born in China, she grew up in Australia and is an Australian national. Her page and video clips on CGTN website have been scrubbed.

On 31 August, the Australian foreign minstry confirmed she had been detained, with Australia's ABC saying she is being held under Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL), a custodial system that places the victim without access to any legal help at a secret facility for up to six months without charge. It was the same system used to initially detain the two Canadian Michaels (see below) and another Australian citizen, writer Yang Hengjun, in the past two years.

There's no information as to why she is being held, but Australia-China relations have soured in recent years with Australia calling for an international inquiry into the origins of the Coronavirus pandemic and most recently a decision by Canberra to enact legislation that would force local governments and institutions to get final approval for any deals with foreign governments from the foreign affairs minister. This is largely seen as cracking down on deals made with China, such as Belt and Road projects and Confucius Institutes.

Timeline of Ms Cheng's Disappearance

- 12 AUGUST: Cheng writes her last social media post

- 14 AUGUST: Australia's Foreign Ministry told that she had been detained

- 27 AUGUST: Diplomats are given video link access to Cheng; reports that conditions are "OK"

- 31 AUGUST: Australia makes news public that she has been detained; Australian news channel ABC says she's being held in RSDL

For more on RSDL, see Safeguard Defenders new report, Rampant Repression, that shows that around 20 people a day are disappeared into this feared custodial system.

The CCP's Coercive Diplomacy

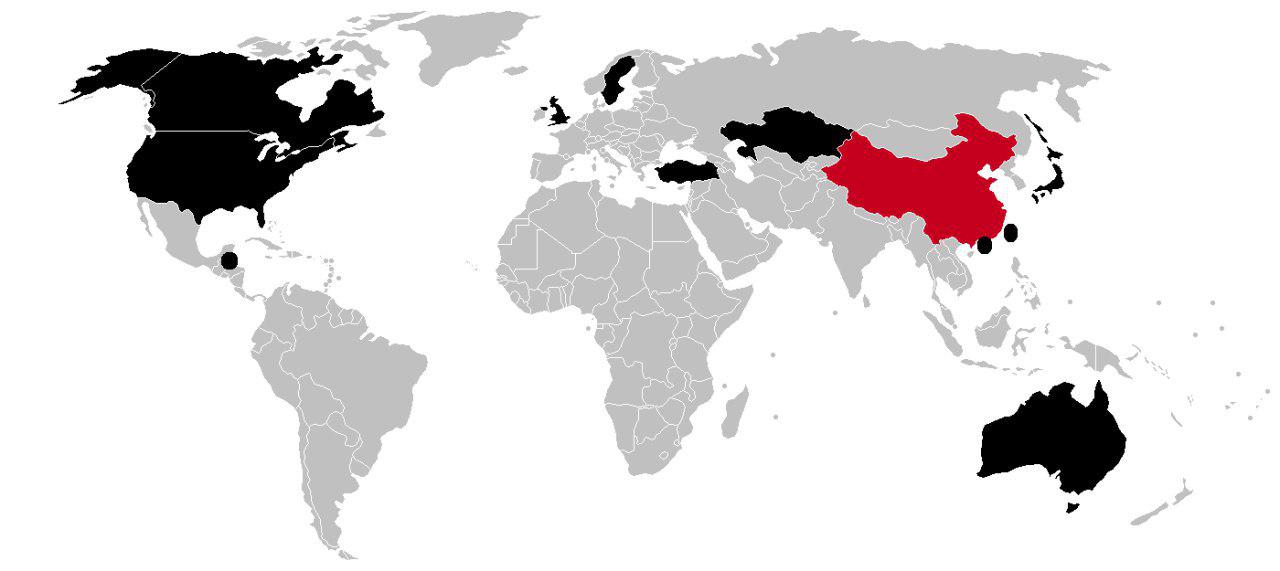

A report out today by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute called The Chinese Communist Party's Coercive Diplomacy found 152 cases of coercive diplomacy affecting 27 countries in the past decade. As well as arbitrary detentions, this includes trade sanctions, tourism bans and restrictions on official travel and are aimed at punishing "undesired behaviour" over issues such as territorial claims, Huawei's 5G technology, criticisms of its human rights policies in areas like Xinjiang, and how it handled Covid-19.

Unwelcoming nation

The main targets of China’s hostage diplomacy in the past 12 months have been Canada for not freeing Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou from a US extradition request and Australia, first for failing to ratify an extradition treaty with China, and then for criticizing Beijing’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic and calling for an international inquiry into the origins of the disease.

Expect to see more UK victims in the near future too as the UK opens a citizenship path for some 3 million Hongkongers and passed further restrictions on Huawei and its role in its future 5G network.

These are some examples of China's hostage diplomacy since the beginning of this year.

Harsher sentences

- At the end of June, China sentenced Canadian citizen Sun Qian to eight years for belonging to the banned spiritual group Falun Gong. The decision came just days after Canada said it would not use political powers to free Meng.

- Australian citizen, Karm Gilespie, was sentenced to death for drug smuggling in early June, five years after his trial.

Citizenship theft

By forcing overseas Chinese who have become naturalized citizens of other countries to renounce their new citizenship, China can more easily deny them consular access in detention, prison and prevent embassy staff attending their court trial.

- Canadian Sun (see above) was born in China but held a Canadian passport. According to her lawyer Xie Yanyi, who was not allowed to represent her, she was forced to renounce her Canadian citizenship.

- While he was kept incommunicado at an unknown location, Swede Gui Minhai was alleged to have renounced his Swedish citizenship to become “Chinese” again. Stockholm said they had no record of this change and did not recognize it. Gui was handed down 10 years for “providing intelligence” overseas in February. The impossibility of Gui regaining his citizenship through legal procedure was expanded upon by Safeguard Defenders Peter Dahlin in an article in Hong Kong Free Press. Gui’s revoking his citizenship and regaining his prior, Chinese citizenship, follows UK citizen Lee Bo undergoing the same treatment in 2016.

Arrests

- Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor's cases were moved to indictment on espionage charges on 19 June, shortly after a Canadian judge ruled against Meng in the extradition case. The two Michaels were first detained and held in RSDL (a type of incommunicado detention at a secret location) in December 2018 following Meng’s initial detention at a Canadian airport.

Detentions

- More than half a year after Yuan Keqin, a Chinese national but long-time resident of Japan, had gone missing in China, Beijing finally admitted it had detained the professor on suspicion of spying in March.

China’s hostage diplomacy by country

In recent years, Citizens of at least seven countries or regions—the US, Taiwan, Japan, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Hong Kong and Belize, and including a consular official and a university professor—have been disappeared in China in what appears to be arbitrary detentions, many accused of national security crimes, others caught up in the vast network of concentration camps in Xinjiang. And these are just the high-profile ones that media report.

For more on China's hostage diplomacy see here.