The cruelty of prisons in China

“A prisoner may, during the service of his sentence, correspond with others, but their correspondence shall be examined by the prison. If the prison discovers that the contents of a letter present a hindrance to the reform of the prisoner, the prison may confiscate the letter.” (China's Prison Law, Article 47)

Life in a Chinese prison is harsh. Our research and studies by others have shown that prisoners often deal with compulsory labour, the threat of extended solitary confinement, intermittent violence, poor quality food, lack of access to the outdoors, and pressure to write “confession letters.”

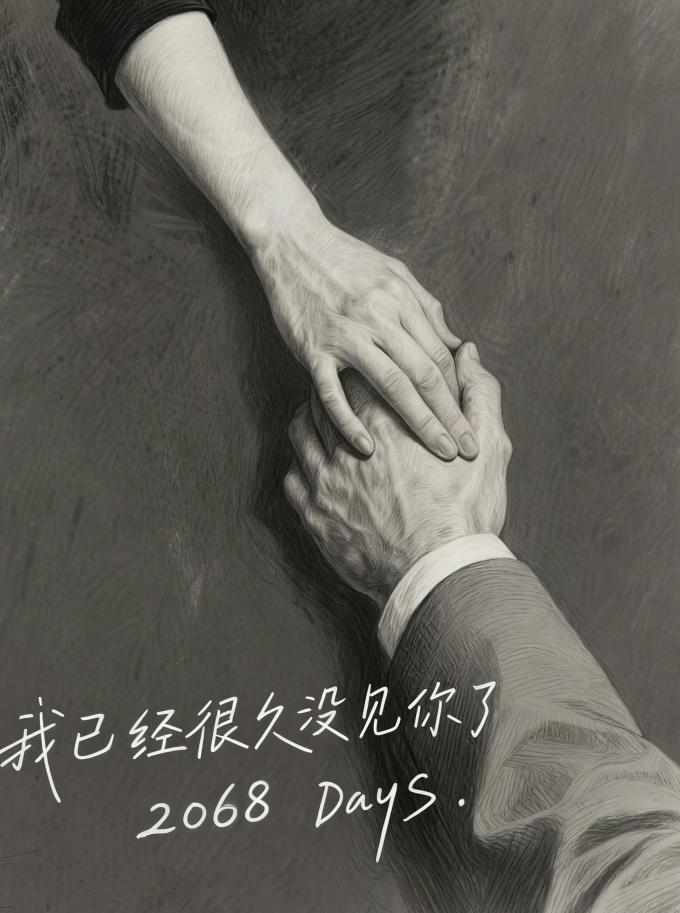

Life is so hard that the right to communicate with the outside world through letters, calls and visits is a crucial lifeline both for those incarcerated and loved ones outside desperate for news.

That’s why when Chinese women’s rights activist Li Qiaochu found that a prison was stopping her letters to her fiancée Xu Zhiyong this July she began to worry.

When it comes to visits and calls, China restricts contact to verified close family members only but correspondence is open to anyone. The only caveat is that all letters, in and out, will be reviewed and censored and maybe withheld if the prison deems it would affect the “reform” of the prisoner -- and this process may mean delays of several months before letters can get through.

Xu is one of China’s most renowned civil rights activists and legal scholars. He is serving an unusually harsh 14-year sentence in Lunan Prison, Shandong province on trumped up charges of state subversion. This is not the first time that letters between the two were stopped. Last year Xu went on hunger strike to protest his inhumane conditions and denial of communications between him and Li, sparking a campaign by his supporters to draw attention to his situation. You can read more about that here.

Li has been one of his biggest advocates. She was only released in August 2024 herself, after serving her own sentence of 3 years and 8 months, in part seen as punishment for speaking out about Xu’s torture in detention in 2021.

Below is the English translation of Li’s recent account on her blog of her intense anguish at being unable to exchange letters with Xu.

On 8 July 2025, I wrote a letter to Xu Zhiyong and mailed it the next day. On July 28, Lunan Prison in Shandong Province, I heard verbally through a third party, orally informed me that I needed to delete the second paragraph on the first page before resending it, and that my original letter would not be returned.

On 30 July, I resent the revised letter as requested.

On 26 August, I was informed that Lunan Prison continued to withhold the letter, claiming it had “not been modified,” even though I had already made the required changes. Xu Zhiyong also confirmed in his early-September letter that he had not received it.

Previously, although my letters were frequently subjected to long and complicated reviews, I usually got his letters to me without too much trouble. Now, correspondence boths ways has been completely cut off for almost a month.

During Mid-Autumn Festival, I wrote a song to express how distressed I’ve been feeling from this enormous physical and emotional pressure. My anxiety from our extended loss of contact keeps growing. In his early-September letter, Zhiyong mentioned that I hadn’t responded to his questions. I’ve wanted so much to tell him: “I did respond, but you never received it.” I don’t know whether, after nearly a month of interrupted correspondence, he thinks I’m sulking and have stopped writing. He has absolutely no way of knowing how hard I’ve been trying to get my letters delivered to him.

From the start of August until now, I have tried so many ways.

- I’ve written three times to the prison requesting written notification of required changes and updates on the handling of correspondence — no reply.

- I’ve submitted two petitions to request a review to the Shandong Provincial Prison Administration — no reply.

- I’ve filed two information disclosure requests concerning the withholding and review of the July 8 letter — I was told a response would be delayed.

- I’ve submitted one application for prosecutorial investigation — no response.

- Yesterday, I had no choice but to file an administrative reconsideration over the withholding of my letter. The filing shows it has been received and is now in process.

By my count, I have sent a total of nine legal documents for this one letter, which I had already revised according to the prison’s requirements.

Yet by the end of August, the prison told me: “Don’t send any more legal documents to the prison or the prison administration department.”

So I don’t understand:

- Why a letter, which was revised exactly as the prison requested, is still considered “not amended” and keeps refusing to deliver it to him?

- Why nine legal documents have received no substantive response, and why were they all met with delays, making resolving this issue further and further into the future?

Clearly, the simplest solution would be for the prison to tell me dorectly how they want me to modify the letter, and I am willing to cooperate with any reasonable requests. Yet the prison has artificially created obstacles for me. Why must I repeatedly encounter such difficulties? I will continue to write to him, but I do not know how many more letters will fail to reach him.

He and I only want to maintain the most basic communication and emotional connection, but I have clearly exhausted nearly all channels.

What else can I do?

On 16 October, Li finally got a letter from Xu, dated just over two weeks earlier, in which he confirmed he had received two letters from her in September, but not the one she had written and rewritten in July.

Also, on 18 October, the Shandong provincial government rejected her request for reconsideration for withholding that letter to Xu, saying the prison, not the government was responsible for censorship of communications. This highlights another problem with prison conditions in China--the lack of defined, transparent and effective measures of complaint or redress for abuses or perceived abuses.