New information suggests UK's Ian Stones held in RSDL

This past week has seen extensive coverage of the previously undisclosed detention and imprisonment of UK citizen Ian Stones on spying charges. His detention and arrest (2018) and subsequent imprisonment (2022) had previously been kept from the public. According to the Wall Street Journal and what would be in line with China's consistent violations of consular treaties, UK consular authorities were prevented access to his sentencing hearing.

On the basis of a witness statement, SD can now release information about the case of Ian Stones, not previously known nor reported on.

For media inquiries, contact Safeguard Defenders.

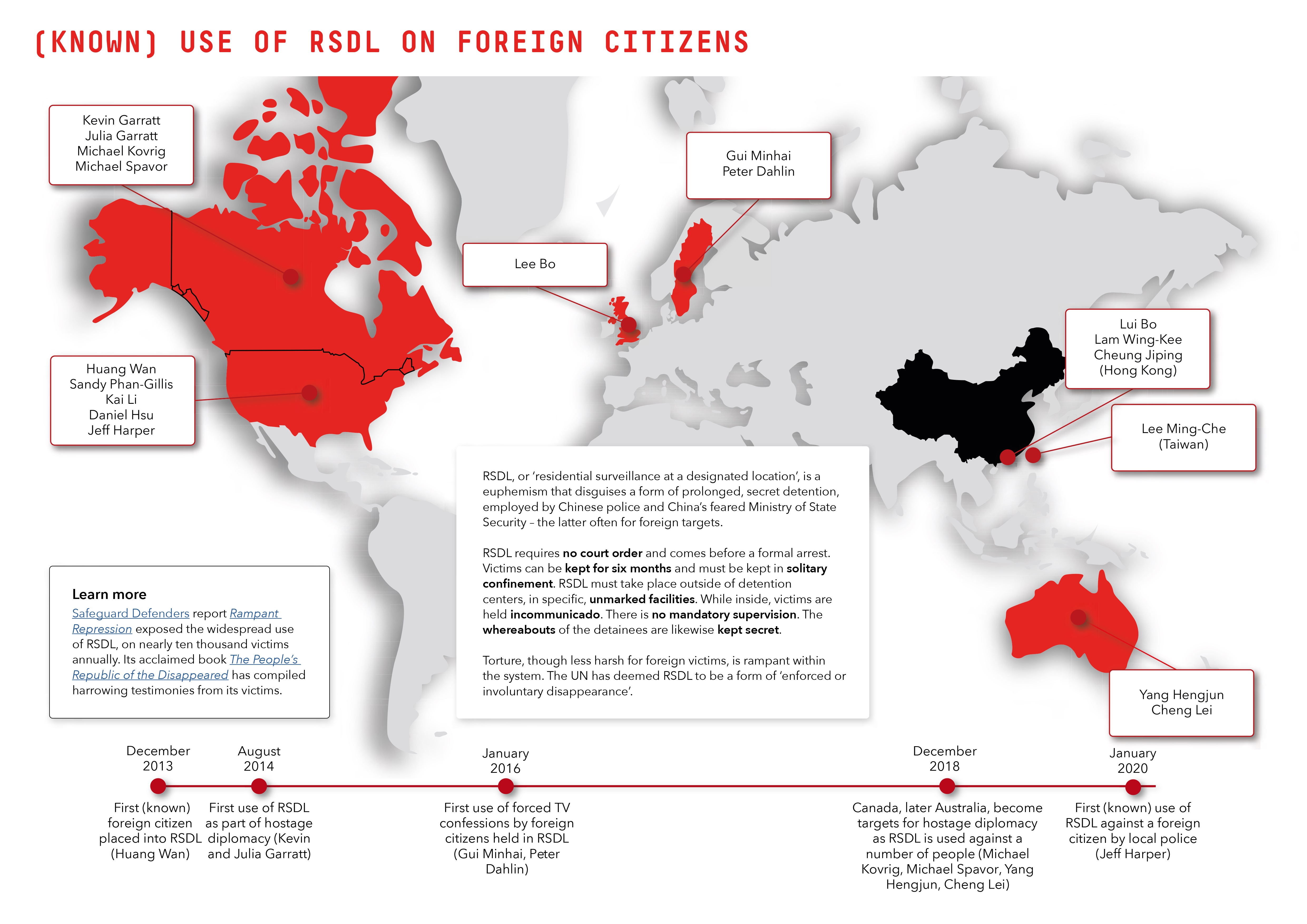

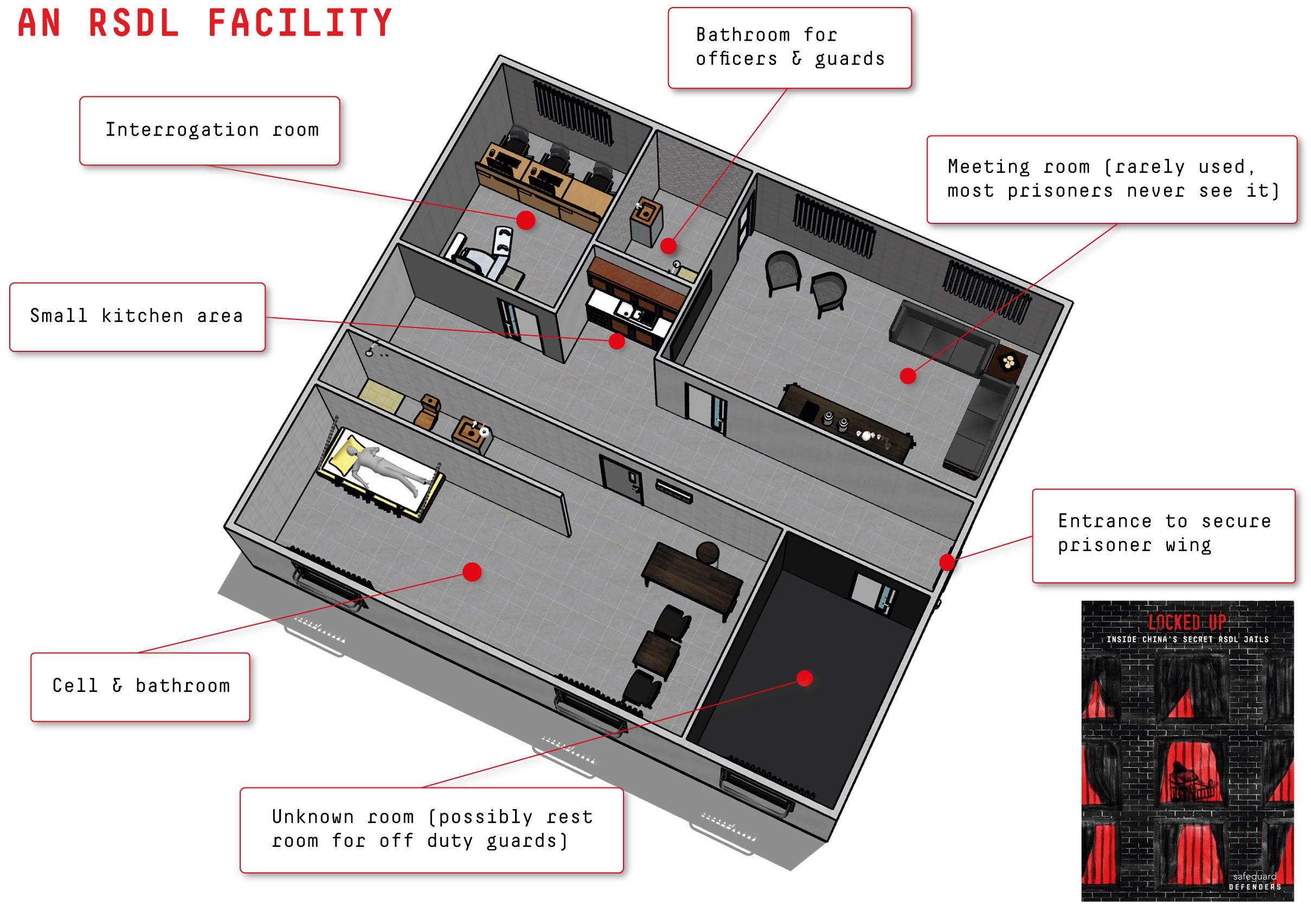

Stones was kept in the below-pictured facility in southern Beijing, former Canadian diplomat and International Crisis Group adviser Michael Kovrig has said, who was himself also a prisoner there. This center also includes a Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) facility, used by the Ministry of State Security (MSS) in cases concerning foreigners or allegations of espionage and other national security-related crimes.

The H-shaped building on the lower right side is the RSDL facility, part of a large detention facility located just off Beijing's old southern Nanyang airport, 大红门看守所 (Dahongmen Detention Centre). The structure has four floors in two wings, each wing holding one victim. The facility can hold eight people at the same time.

Like Kovrig and Safeguard Defenders' own Peter Dahlin, Stones was detained in Beijing by the MSS and almost certainly placed into that RSDL facility.

Safeguard Defenders' graphics-heavy report on RSDL, #LockedUp, is focused on that very facility, with artwork and models to illustrate “life inside”.

Safeguard Defenders' graphics-heavy report on RSDL, #LockedUp, is focused on that very facility, with artwork and models to illustrate “life inside”.

Three pieces of information all points to Stones being in RSDL for the first period after his apprehension:

- Placing Stones in RSDL best explains the denial of all consular access for about six months, as reported by the Wall Street Journal. Six months is the legal limit placed on RSDL detention under Chinese law (though often violated). Later, when Stones was in regular detention, his family and the embassy were given (sporadic) access.

- Stones, first detained in late 2018 (exact date still unknown), was transferred to the next-door regular pre-trial detention facility shortly after Kovrig was moved there in April 2019 after his own five months of RSDL. Stones likely followed a similar timeline and process, or else he would not have arrived there after Kovrig. Kovrig said, “He was transferred to the detention center right after me, but in we were held in separate cells and never had an opportunity to interact. I learned of his existence because I once received his English books by mistake”. He also heard about Stones from one of his later cellmates, who had previously shared a cell with Stones.

- His five-year sentence, had he not been placed into RSDL, would have led to his release by now, as each day in regular detention counts as one day off a sentence, while time spent in RSDL counts only as a half day. Hence, without RSDL, he could not (legally) still be in prison.

It seems nearly certain that Stones was first held at the RSDL facility after his initial detention, likely for six months.

If true, it would be the ninth case known to Safeguard Defenders of MSS placing people accused of national security-related crimes into that facility and the fifth foreign citizen placed there.

Based on Kovrig's statement, it is now also known that the general detention facility at this location (not the RSDL facility itself) also held Australian journalist Cheng Lei, two other Canadian citizens, later espionage convicted Japanese man Hideji Suzuki, and one other Japanese citizen. Kovrig confirms that Suzuki was also in the RSDL facility earlier.

Given that he was sentenced to five years, based on the time he served in RSDL and under pre-trial detention, Stones should be set free around March this year at the latest.

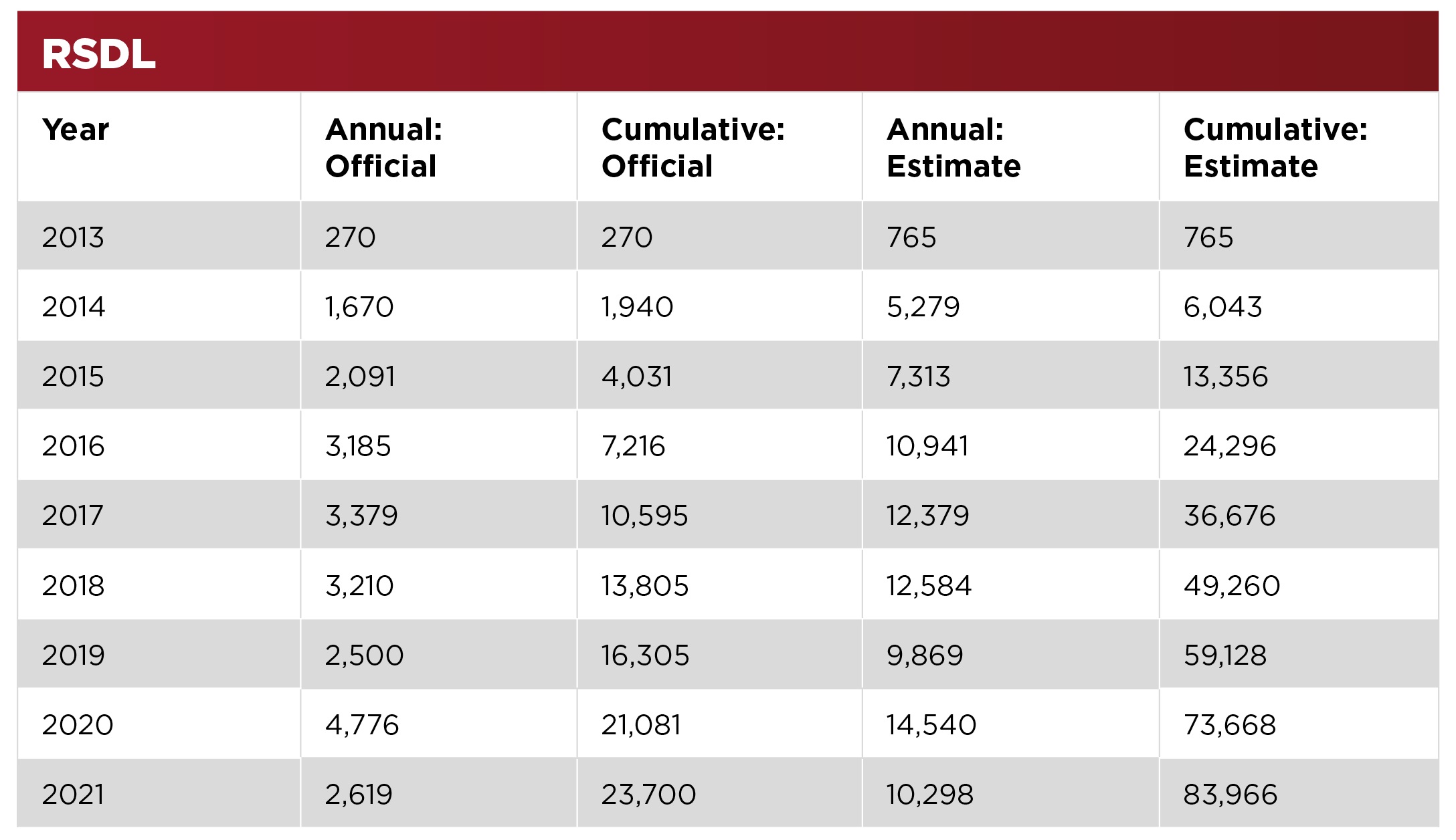

China’s use of RSDL started increasing significantly around 2016/2017. It is estimated that some 10,000 to 15,000 people are placed into the system each year, with a likely estimate of around 100,000 victims since it was put in place in 2013. The government itself acknowledges at least some 25,000 cases.

[See a summary of relevant data, provided in mid 2023 to relevant UN Human Rights Procedures]

In 2018, ten different UN bodies, following an evidence submission by SD and several other Human Rights NGOs, concluded that the use of RSDL is tantamount to enforced disappearances (i.e., state-sanctioned kidnapping). Inside, there is a significant risk of torture and forced confessions. The use of prolonged solitary confinement (and all RSDL is in solitary confinement) for investigation purposes, the UN has concluded, is in and of itself an act of torture, causing permanent, irrevocable damage.

Safeguard Defenders holds that China's proven systematic and widespread use of enforced disappearances RDSL constitutes a crime against humanity under the terms of the Rome Statute.

For more on the reality inside RSDL, see Safeguard Defenders report Locked Up, set in the above facility.