Non-Release Release turns freedom in China into an illusion

On 5 April 2020, after almost five years of being disappeared by the Chinese state, human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang was due to be released from jail. He walked through the gates of Linyi Prison in Shandong province and straight into a police car. But instead of being taken home to reunite with his wife and son, he was driven to the provincial capital, Jinan, a city 400km away from his family in Beijing.

On 5 April 2020, after almost five years of being disappeared by the Chinese state, human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang was due to be released from jail. He walked through the gates of Linyi Prison in Shandong province and straight into a police car. But instead of being taken home to reunite with his wife and son, he was driven to the provincial capital, Jinan, a city 400km away from his family in Beijing.

Officers placed him under house arrest and then later confined him to the city under police escort. It took another three weeks and a family emergency – his wife was rushed to hospital with acute appendicitis – for police to finally allow Wang to go home.

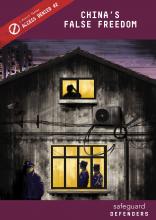

A new report out today by Safeguard Defenders, Access Denied #2: China’s False Freedom is the first in-depth study into what has become known as Non-Release Release (NRR)* or weishifang (伪释放) in Chinese, in which prisoners, once freed from jail or a detention centre, are arbitrarily detained by the police at their home, at a hotel or in a secret location for weeks, months or even years.

Read the report in English here or in Chinese here.

“The phenomenon of non-release release is yet another example of systematic illegal behaviour by Chinese police that makes a mockery of China’s justice system,” says Peter Dahlin, founder and director of Safeguard Defenders. “It renders serving your sentence or being released on bail meaningless, when being freed simply means being moved into another form of imprisonment.”

China’s False Freedom features interviews with victims, including an account by Angela Gui of how her father, imprisoned Swedish publisher Gui Minhai, was kept under months of NRR in Ningbo before he was abducted on a train in front of Swedish diplomats in broad daylight – the second such kidnapping of Gui by Chinese state agents. The report also culls data from interviews and online sources to track dozens of NRR cases since 2014.

Our research showed that it is has now almost become standard practice for police to impose NRR on “freed” activists and lawyers. While NRR may last from a few days to several months, others can languish for years. Lawyer Gao Zhisheng is in the middle of six years of NRR; he remains disappeared by the state to this day. Another rights lawyer, Jiang Tianyong, despite his two-year prison sentence for inciting state subversion officially ending on 28 February 2019, is watched, even today, by 20 black-clad “minders” every day and may only seek treatment for medical problems stemming from his torture in RSDL and detention) with a police escort.

NRR may take the form of house arrest, enforced travel and confinement to a hotel room, or confinement at a police-owned facility. While Chinese police employ many kinds of arbitrary detention, NRR is the only one that is imposed on a victim immediately after they have spent months or even years in custody and thus represents a particular cruelty on the victim and their loved ones.

It violates Article 37 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China, which protects the personal freedom of citizens. It also violates international rights laws pertaining to the right of liberty and freedom of movement. For the most serious forms of NRR, where the individual is disappeared, it amounts to an enforced disappearance as defined in the UN Convention for the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearances.

Guards often sleep in the same room as the victim; there is no freedom to leave; no freedom to contact friends and family; even access to medical care is controlled. Hotels or rented apartments are the most common locations for NRR and police impose it across the whole of China, from the far north-eastern province of Heilongjiang to Guangdong in the south.

China’s False Freedom is the second in our three-part Access Denied series, which examines the serious deterioration in the rule of law in China under Xi Jinping. The first edition, China’s Vanishing Suspects, released at the end of 2020, exposed how police are registering detainees under fake names to prevent them meeting with their lawyers or having contact with their loved ones.

*The term NRR was coined by long-time scholar of Chinese law Jerome A. Cohen.