Why China’s history of forced confessions means Peng Shuai-IOC call is not credible

We talk to Dr. Elizabeth Carter about how the press should responsibly cover such fake news and her just published PhD study looking at the linguistics of China’s televised confessions

A 30-minute video call between Peng Shuai and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) was supposed to quell concerns about the Chinese tennis star’s safety, however it raised more questions than it answered. Since the IOC won’t release the video, all we have is a still of the call showing Peng beaming against a backdrop of soft toys.

- We don’t know if she spoke freely.

- We don’t know what they talked about.

- Most crucially, we don’t know what is happening off camera.

From our research into forced televised confessions what we do know is that most often, just beyond the camera lens, is a team of security officials directing the show behind the scenes.

Peng has been incommunicado since November when she posted online allegations that former senior CCP official Zhang Gaoli sexually assaulted her.

The photo of the Peng-IOC call brings to mind the shots of Swedish publisher Gui Minhai in early 2018 when he was paraded in front of the press in a particularly painful forced confession (he had earlier been abducted by security agents in front of Swedish consular officials off a train; in the video he appeared to have lost a tooth). In the eyes of the CCP, Gui and Peng are not so different: Gui published books of salacious gossip about top CCP officials, Peng made public a #MeToo scandal about the man who had formerly led Beijing’s Winter Olympics organizing committee; Games that are set to begin in little more than eight weeks.

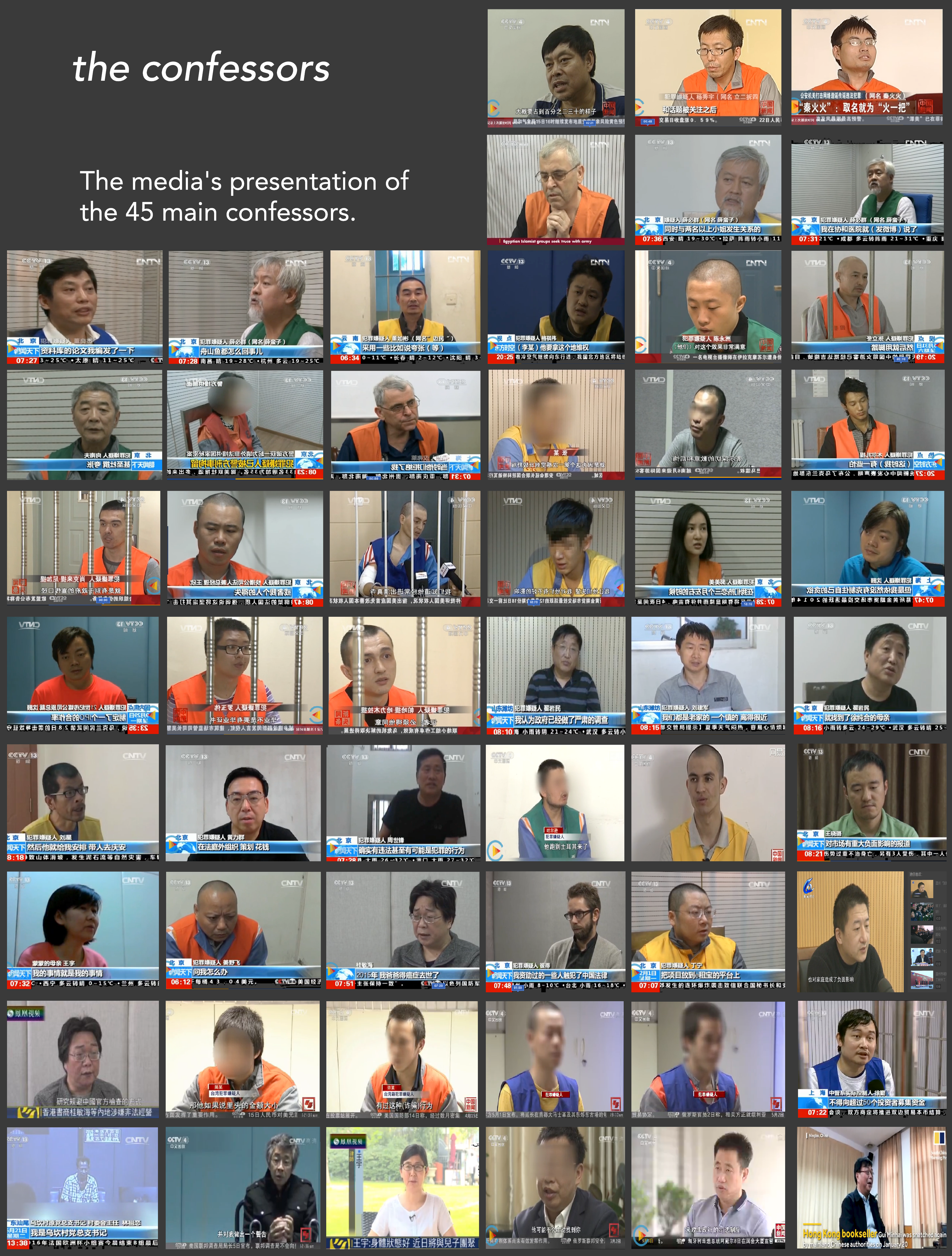

Back in 2018, we analysed 45 broadcast confessions and interviewed victims and found that in many cases police threatened and tortured them to take part: they had to learn scripts, get dressed in costume, and deliver their lines as directed. Since then, high-profile televised forced confessions have declined, but they have moved to different “forms” such as tiger chair humiliation sessions aired on police social media and proof of life videos for persecuted Uyghurs.

Back in 2018, we analysed 45 broadcast confessions and interviewed victims and found that in many cases police threatened and tortured them to take part: they had to learn scripts, get dressed in costume, and deliver their lines as directed. Since then, high-profile televised forced confessions have declined, but they have moved to different “forms” such as tiger chair humiliation sessions aired on police social media and proof of life videos for persecuted Uyghurs.

With China’s track record for fake videos, it is both dangerous and disingenuous of the IOC to take the Peng call at face value.

While Scripted and Staged was the first study of its kind, since its 2018 publication other researchers have begun analysing China’s practice of public confessions. Just published, is a PhD thesis looking at streamed trials and televised confessions by Elizabeth Carter, who warns against reporting on such videos without sufficient context, especially given the high possibility of their coercive nature.

In the interests of giving the true nature of confession or proof-of-life footage from China greater exposure, Safeguard Defenders interviewed Dr. Carter about the key discoveries she made as part of her PhD research.

Q. In reporting on televised confessions from China, what words of advice would you give to non-Chinese media on how to report them with honesty and fairness?

I think reporting on televised confessions requires ethical consideration of the context. Contextualization of any coverage must be sufficient to make clear to the reader the coercive factors at play. Reproducing what is originally said in the televised confession news segments without doing this is merely amplifying them. This was a common characteristic of PRC state media coverage of televised confessions – online articles essentially became text versions of their televised counterparts.

Q. Why do you think China has made televised confessions?

I think televised confessions are the utilization of mass media for political purposes, both foreign policy and domestic issues. Xi Jinping has explicitly stated in his speeches on the role of the media that in the project of “judicial transparency” the media must work with the courts and judiciary to guide public opinion… Perhaps one motivating factor is… to discredit and demotivate the targeted individuals, and yet another could be to vilify so-called foreign forces and thus stoke nationalist sentiment. Of course, stoking nationalism is advantageous because it makes it easier to exercise control domestically.

Q: What did your research tell you about China’s televised confessions?

Q: What did your research tell you about China’s televised confessions?

I looked at three news segments in particular, featuring Gui Minhai, and [rights lawyers] Wang Yu and Zhang Kai. Although these three segments were ostensibly on different subjects, broadcast by different television channels, and focused on different topics, they were remarkably similar in many ways. For example, I looked at the term “China” (Zhongguo) across the three videos – it was largely used in contexts in which it was the object of some negative action, often by foreign forces… I also looked at gaze in the three videos. When they were forced to make a confession, they had downward, indirect gaze. When describing neutral topics, they had level, indirect gaze. When other individuals were featured, sympathetic interviewees had upward, indirect gaze, while police were blurred and shot as if their identities were bring protected. Of course, anchors faced into the camera positioning themselves as the mediating authority between the viewer and confessing subject. This visual messaging conveys the guilt of the subjects just as strongly as the explicit scripts. The b-roll footage of both Wang Yu and Zhang Kai also featured still images of the two in detention, with lowered heads. My final finding.. was that these stances were likely intended to evoke feelings of nationalism and hostility toward foreign forces among audience members.

When they were forced to make a confession, they had downward, indirect gaze. When describing neutral topics, they had level, indirect gaze. When other individuals were featured, sympathetic interviewees had upward, indirect gaze, while police were blurred and shot as if their identities were bring protected.

Q. Why do you think the ‘traditional’ high profile televised confessions have become less common?

My research did not address this question directly, but I think high profile cases have tapered off for a number of reasons. One is that repression always comes and goes in waves. One of the many purposes of political intimidation campaigns is to create a climate in which people stay in line through only the lingering threat of punishment – what Perry Link called the anaconda in the chandelier. Perhaps the legal actions taken by some international broadcasting boards have also sent a message about what will and will not be tolerated. [Safeguard Defenders’ campaign against CGTN ended with the UK’s broadcasting regulator banning it from the country] It may also be the case that with what’s been happening in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, more attention is on the peripheries. And finally, officials have always disavowed the fact that forced confessions are a coordinated campaign. Diversifying the ways in which these messages are disseminated may be another way to create that plausible deniability.

Q. What made you interested in this topic?

The televised confessions as well reflect a very different kind of relationship between media and the law than existed previously. We tend to take our understandings of things like the legal system and the media for granted, they seem solid and beyond question. But if they are changing to fulfill different purposes, I thought it was important that we understood those better.