Chinese police kidnaps writer in Mongolia

Last month, Chinese police descended on the home of historian and activist Lhamjab Borjigin and arrested him. Such arrests are commonplace in the authoritarian country, but his capture did not happen on Chinese soil. It took place in a foreign country – Mongolia.

Chinese police, with Borjigin’s daughter in tow, arrived at his apartment in Ulaanbaatar on 3 May and forcibly took the 80-year-old back to China, according to a close friend of his who lives in the Mongolian capital.

Borjigin had predicted his forced return. A week before his disappearance, he had contacted Southern Mongolian Human Rights Information Centre (SMHRIC), a US-based rights NGO working on Mongolian rights in China, to say that Chinese authorities had been harassing his family back home in an effort to get him to return to China and were threatening to bring his daughter to Mongolia to force him to go back.

This under-reported story of a transnational kidnapping event exposes how easily the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is able to silence activists living outside its borders and is another example of the CCP’s practice of involuntary returns (see our 2022 report Involuntary Returns: China’s covert operation to force ‘fugitives’ overseas back home, and article on the expansion of Sky Net), the CCP’s campaign to return “fugitives” from overseas.

China’s Involuntary Returns

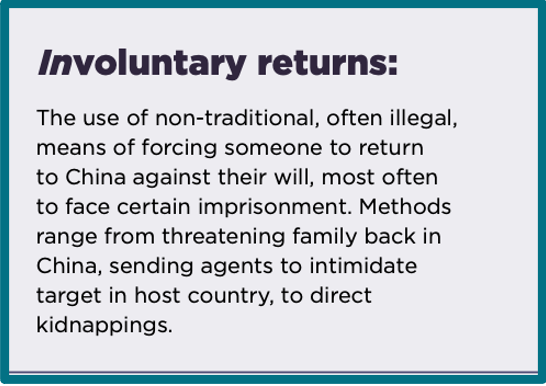

The CCP uses three illegitimate methods - threats to family, intimidation/harassment in host country, and direct kidnapping - outside of bilateral agreements, to forcibly secure the return of Chinese nationals abroad. These are “involuntary returns” in contrast to the CCP’s portrayal of them as “voluntary returns.” They are a serious violation of national sovereignty and another example of China’s expanding transnational repression practices.

The CCP uses three illegitimate methods - threats to family, intimidation/harassment in host country, and direct kidnapping - outside of bilateral agreements, to forcibly secure the return of Chinese nationals abroad. These are “involuntary returns” in contrast to the CCP’s portrayal of them as “voluntary returns.” They are a serious violation of national sovereignty and another example of China’s expanding transnational repression practices.

The CCP’s involuntary returns operations are a global phenomenon. In our 2022 report on China’s involuntary returns, we documented 80 instances against 62 targets in 18 countries and regions (not including Mongolia). Outside of this, the Uyghur Human Rights Project’s Transnational Repression of Uyghurs Dataset has logged hundreds of Uyghurs who have been forcibly returned.

The involuntary return of Borjigin is an example of a Type 3 involuntary return, where Chinese police kidnap wanted targets overseas, with or without the host country’s permission. In this case, it appears that Mongolia had allowed the arrest to take place, although an official statement from the Mongolian government denied that there was any Chinese police operation and that Borjigin left voluntarily via the Zamyn-Üüd highway port in Dornogovi province because his visa was expiring on 5 May.

Repeated requests over a period of three weeks by Safeguard Defenders to Mongolia’s Foreign Ministry’s Press Office for comment has gone unanswered.

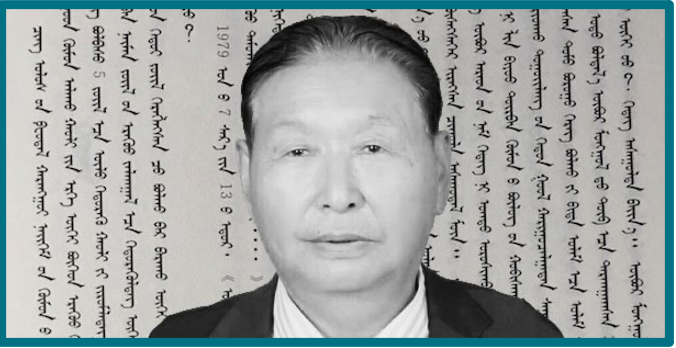

Who is Lhamjab Borjigin?

Borjigin is a prominent historian who gained recognition for his work in documenting the history and culture of Inner Mongolia (also called Southern Mongolia by advocates of self-rule) in China. He spent two decades writing his 2006 book, China's Cultural Revolution (Ulaan Huvisgal in Mongolian), a compilation of oral testimonies of survivors of China's state-sponsored mass killings during the late 1960s in Inner Mongolia in which it is thought that at least tens of thousands of ethnic Mongolians died.

Borjigin is a prominent historian who gained recognition for his work in documenting the history and culture of Inner Mongolia (also called Southern Mongolia by advocates of self-rule) in China. He spent two decades writing his 2006 book, China's Cultural Revolution (Ulaan Huvisgal in Mongolian), a compilation of oral testimonies of survivors of China's state-sponsored mass killings during the late 1960s in Inner Mongolia in which it is thought that at least tens of thousands of ethnic Mongolians died.

He was imprisoned in 2019 for his writing and later placed under a form of house arrest called Residential Surveillance (see Safeguard Defenders' in-depth report Home As Prison). In 2020, the CCP launched a crackdown in Inner Mongolia following protests against plans to stop using the Mongolian language in schools. In March 2023, Borjigin escaped to Mongolia where he was hoping to publish more of his writing.

Involuntary returns and deportations

Borjigin’s case is likely the fifth known example of an involuntary return to China from Mongolia since 2009. Several previous deportations of ethnic Mongolian Chinese activists were conducted swiftly and without obvious due process: a deportation can be considered an involuntary return type 3 if proper procedures are not taken, in other words the host country uses the guise of a deportation to allow Beijing to conduct an involuntary return.

In 2009, Batzangaa, a Chinese national and ethnic Mongolian was applying for asylum in Ullaanbaatar when he was apprehended by Mongolian officers and then handed over to Chinese police in the capital. Batzangaa, who had headed a Mongolian-Tibetan medical college in China, was then sent back with his wife and child. He was later sentenced to three years in prison for what he says were trumped up charges because his work involved the sensitive issue of promotion of ethnic cultures.

In 2014, activists Dalaibaatar Dovchin and Tulguur Norovrinchen were detained by Mongolian police before they were to give a press conference on raising attention about another ethnic Mongolian man from China who was in danger of being deported. Both men had legal status in Mongolia. Tulguur had been threatened with deportation but had applied for asylum status with the UNHCR. Both were deported by train shortly afterwards but have not been heard from since.

According to SMHRIC, also in June 2014, Mongolia deported 70-year-old activist Unenbaatar Loojab to China. His whereabouts are also unknown.

Chinese influence in Mongolia

China is more easily able to achieve type 3 involuntary returns in other authoritarian countries -- such as Laos and Cambodia -- sometimes with the help of local authorities. What’s surprising in the case of Mongolia is that China was able to kidnap its citizens from a democratic country and with its assistance or at least permission.

However, these deportations or involuntary returns have taken place as Beijing enjoys growing influence over Ulaanbaatar. In recent years, Mongolia has amassed debts to China, amounting to billions of dollars.

In addition to permitting or assisting in China’s involuntary returns, the country has become intolerant of any public protest against Beijing.

-

In 2015, eight local activists who protested in front of the Chinese Embassy in Ulaanbaatar to demand the release of herders in Inner Mongolia were detained.

-

In 2022, Mongolian activist Munkhbayar Chuluundorj was sentenced to 10 years after he criticized his country’s close relationship with China. He was accused of “collaborating with a foreign intelligence agency.”

Forced return to China

China and Mongolia have ratified a bilateral extradition treaty, but such requests typically involve lengthy procedures. There are no known extradition cases that have been carried out by the Mongolian government.

Furthermore, a string of court cases in Europe and a 2022 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights have rejected China’s extradition requests on grounds on serious concerns that returnees would be subjected to torture or ill-treatment. China often prefers to use deportations or illegal means such as involuntary returns to capture a target overseas and bring them back home.

The CCP’s involuntary returns operations on foreign soil pose a direct threat to the safety of Chinese activists living in exile and to the national and judicial sovereignty of host countries. Victims of China’s involuntary returns will not be given a fair trial when their rights to remain in a country and to be awarded due process have already been undermined by their forced return, not to mention that they are at high risk of torture or ill-treatment once inside China's judicial system.