Home Becomes Prison – China’s expanding use of house arrests

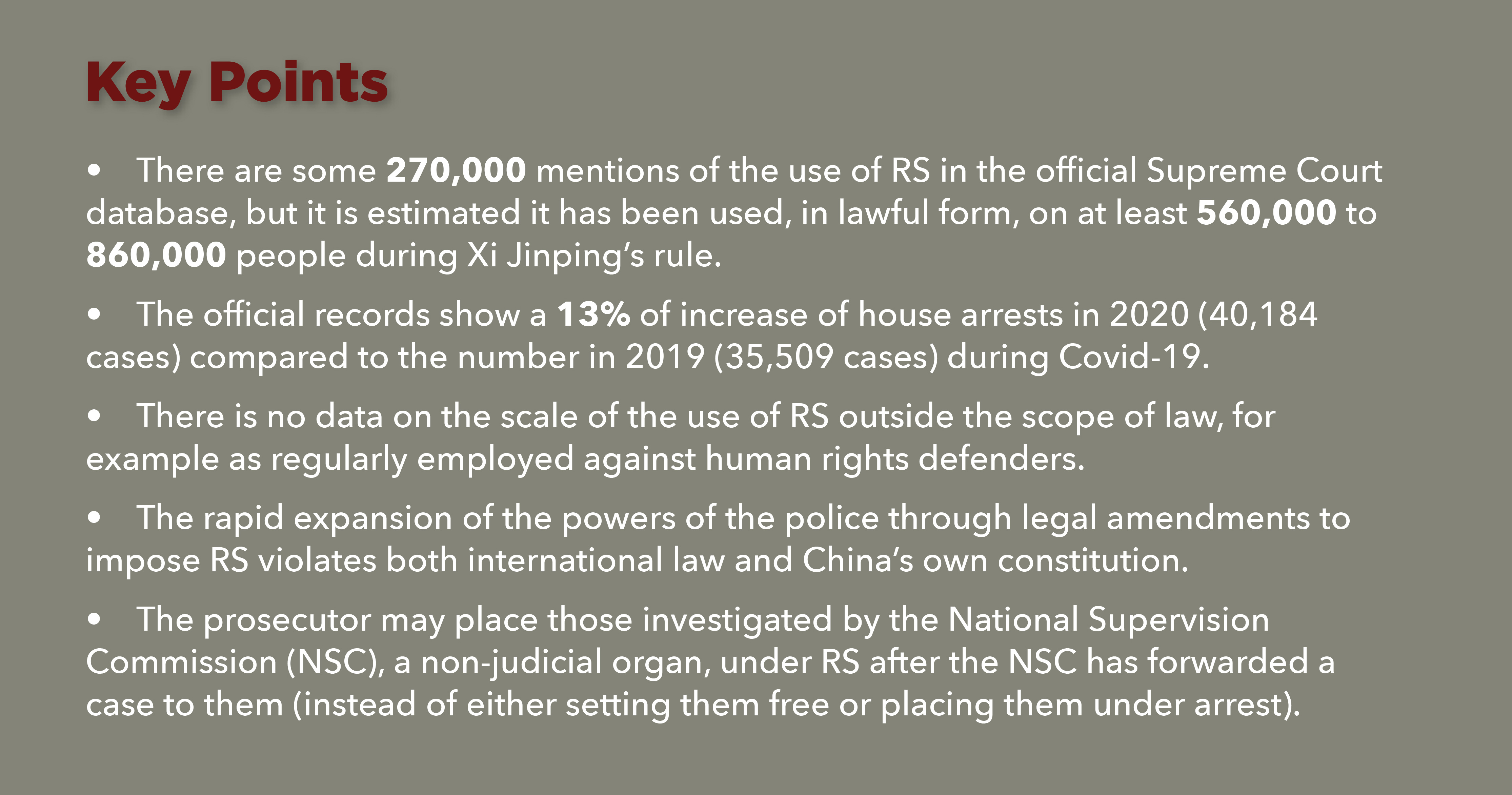

New data from the Chinese government shows a remarkable use of house arrests under Xi Jinping, in the hundreds of thousands. Alongside an increase in use, two major revisions to the Criminal Procedure Law - in 2012 and 2018 - have further codified its use. The room for abuse is significant.

New data from the Chinese government shows a remarkable use of house arrests under Xi Jinping, in the hundreds of thousands. Alongside an increase in use, two major revisions to the Criminal Procedure Law - in 2012 and 2018 - have further codified its use. The room for abuse is significant.

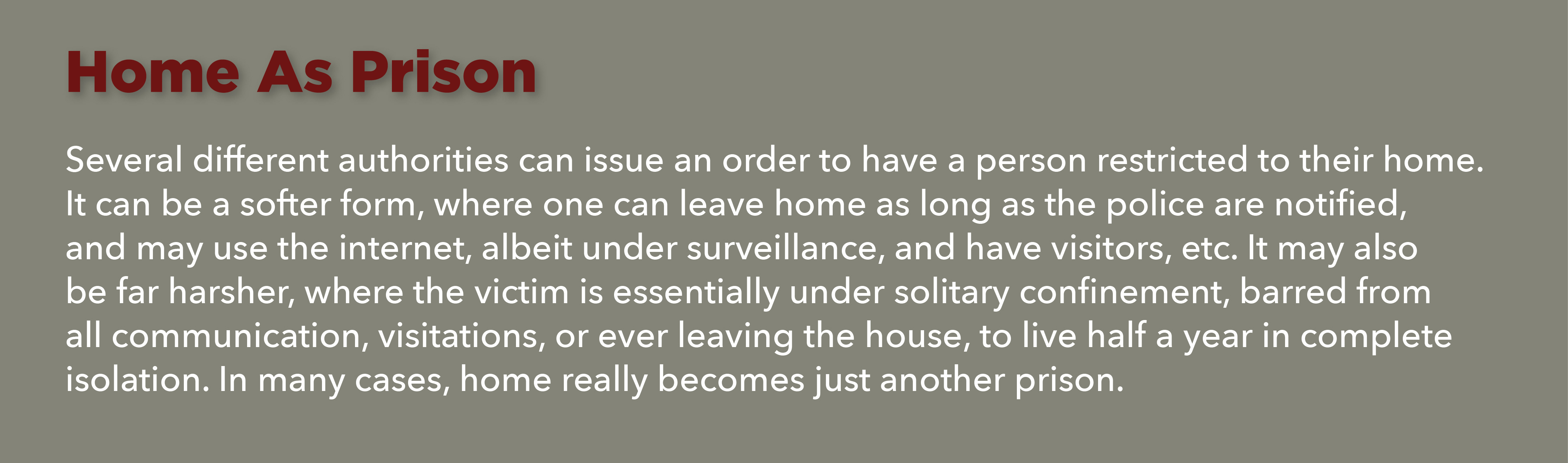

Today’s new report Home As Prison provides the first systematic insight into the long-standing practice of the Chinese police to detain people under house arrest, both through lawful measures as codified by law, as well as via arbitrary and entirely illegal means, the latter often used to target human rights defenders.

Click here to download Full Report as PDF.

Click here to download 1-page Executive summary as PDF.

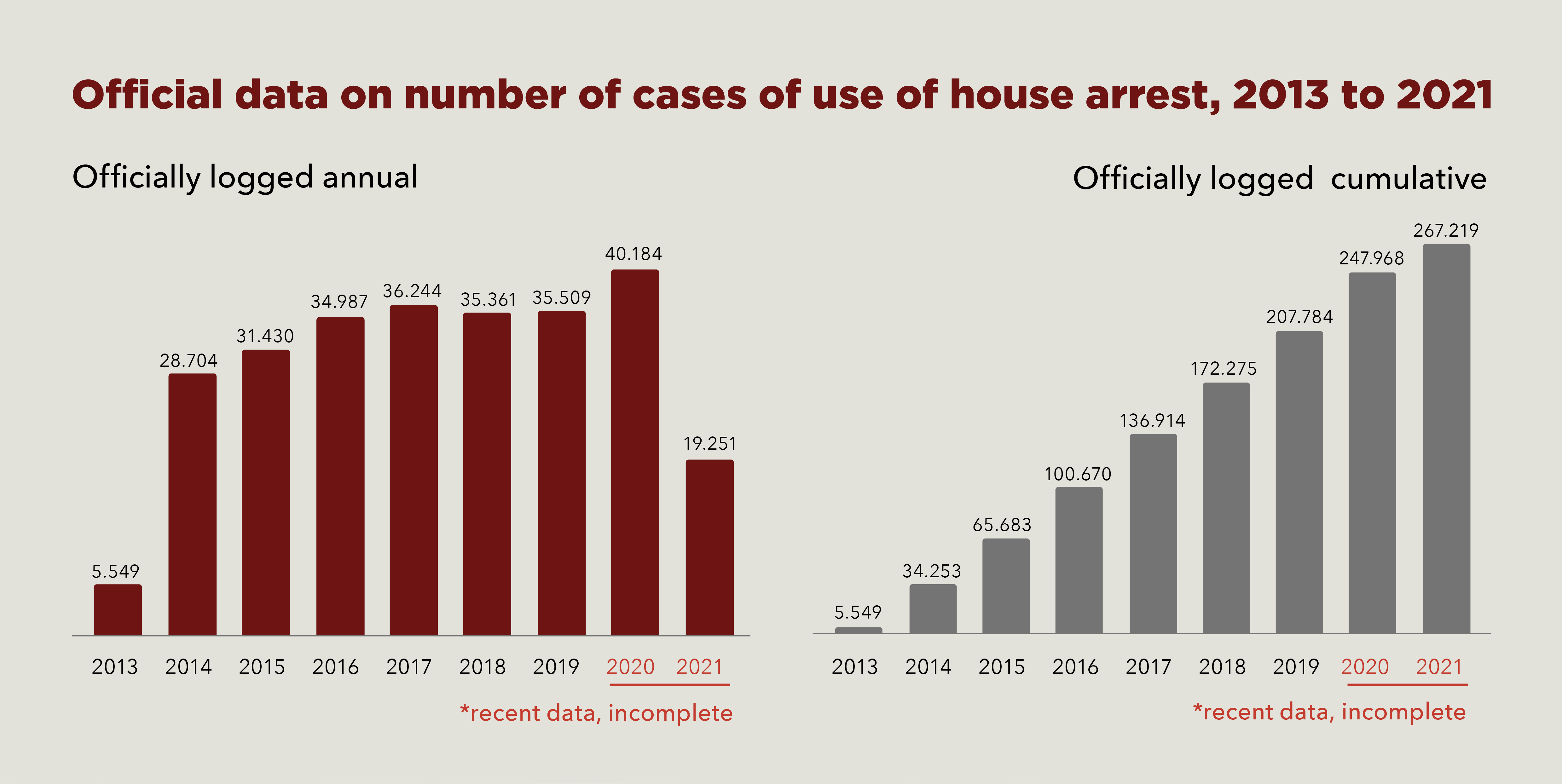

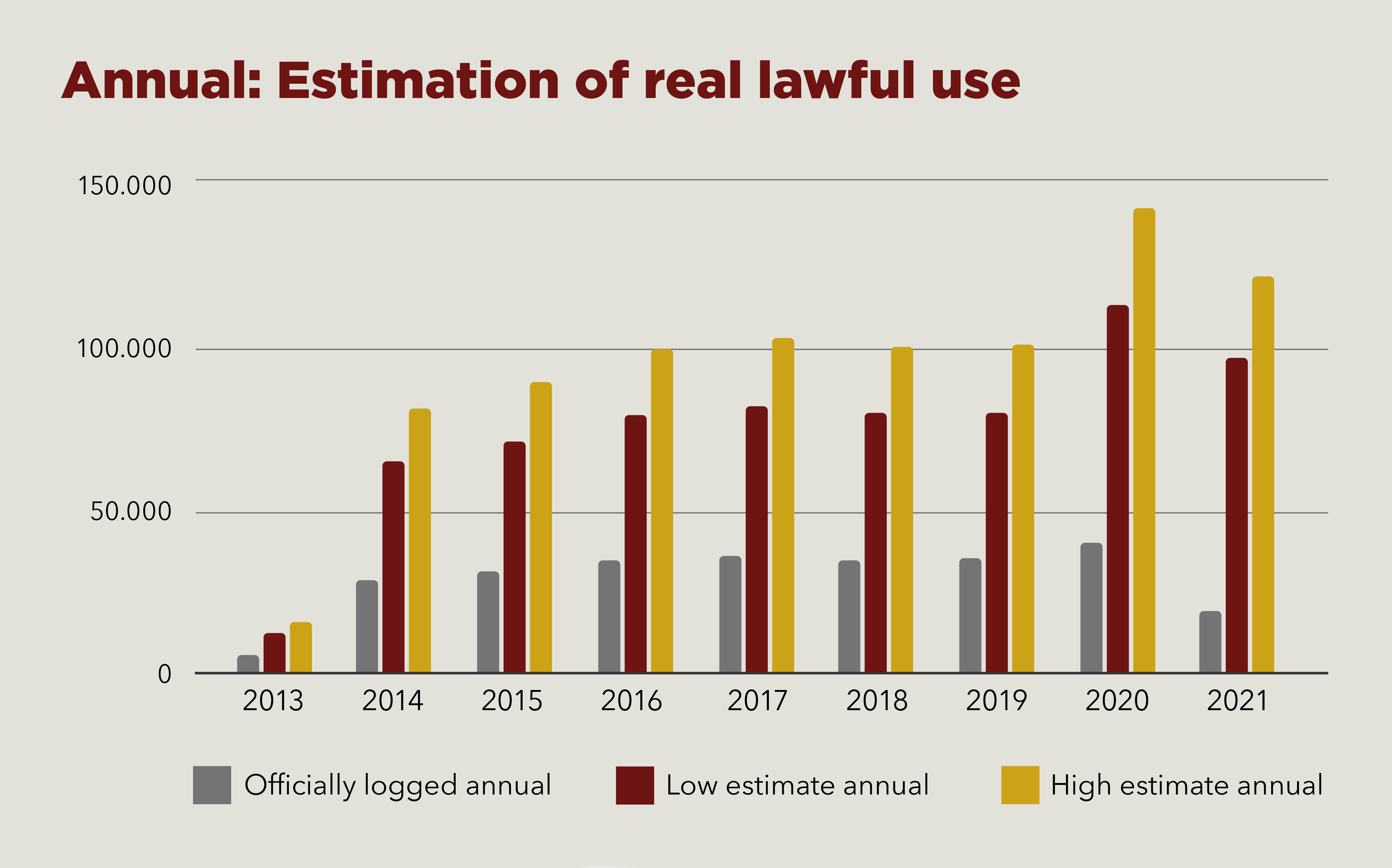

The use of house arrests reached a record high in 2020 - the first year under the Covid pandemic - but had already established itself on a high level before Covid hit.

All data points to the significant increase of what was at first a special measure - very rare when Xi Jinping first came to power - since 2014/2015, with no end in sight to its continued mass use.

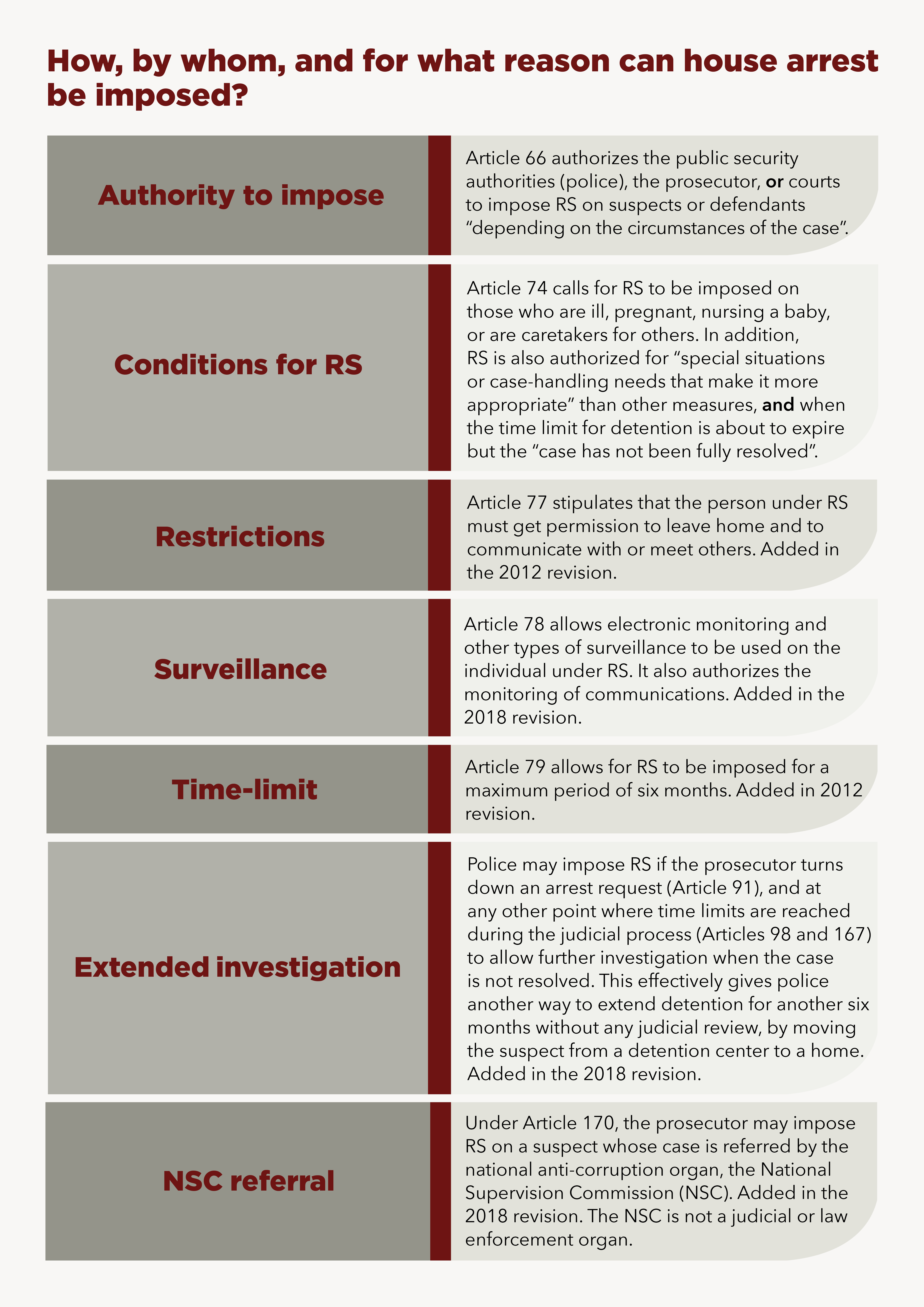

As a slew of cases presented in Safeguard Defenders’ brand-new report Home As Prison shows, house arrests - or “Residential Surveillance” (RS) - is not merely used by police when arresting someone is not suitable. It is instead used in a myriad of ways, allowing police, prosecutors and courts to essentially keep people detained, even when formal time-limits in the judicial process have been exhausted. It is a powerful weapon that allows the authorities to keep suspects under control even when detention or arrest is no longer legally permissible.

The scope for abuse of immense, as no judicial review is required. If the prosecutor refuses a request from the police to have someone arrested, for example, the police itself can simply lock the person up in their home, for half a year, and keep them incommunicado.

Knowing fully well that the Wenshu - or China Judgments Online (CJO) - database run by the Supreme Court is very incomplete (see Safeguard Defenders’ study on the issue: China’s Missing Verdicts), that the prosecutor drops a portion of cases before trial (which thus never end up in the database) (see Safeguard Defenders study on China’s criminal justice system in the Age of Covid), as well as several other variables - such as the average number of people per case (which, like in most countries, is higher than 1 on average) -, two estimates, a lower and a medium one, have been used to present a more realistic assessment of the true scale of its use. Despite the shocking numbers, these estimates are modest in most ways and err on the side of caution.

Safeguard Defenders, drawing on official government data from the Supreme Procuratorate and Supreme Court, along with studies by Chinese academics, estimate that the real number of persons affected stands between 566,585 (lowest estimate) and 862,757 (highest estimate) people for the corresponding period.

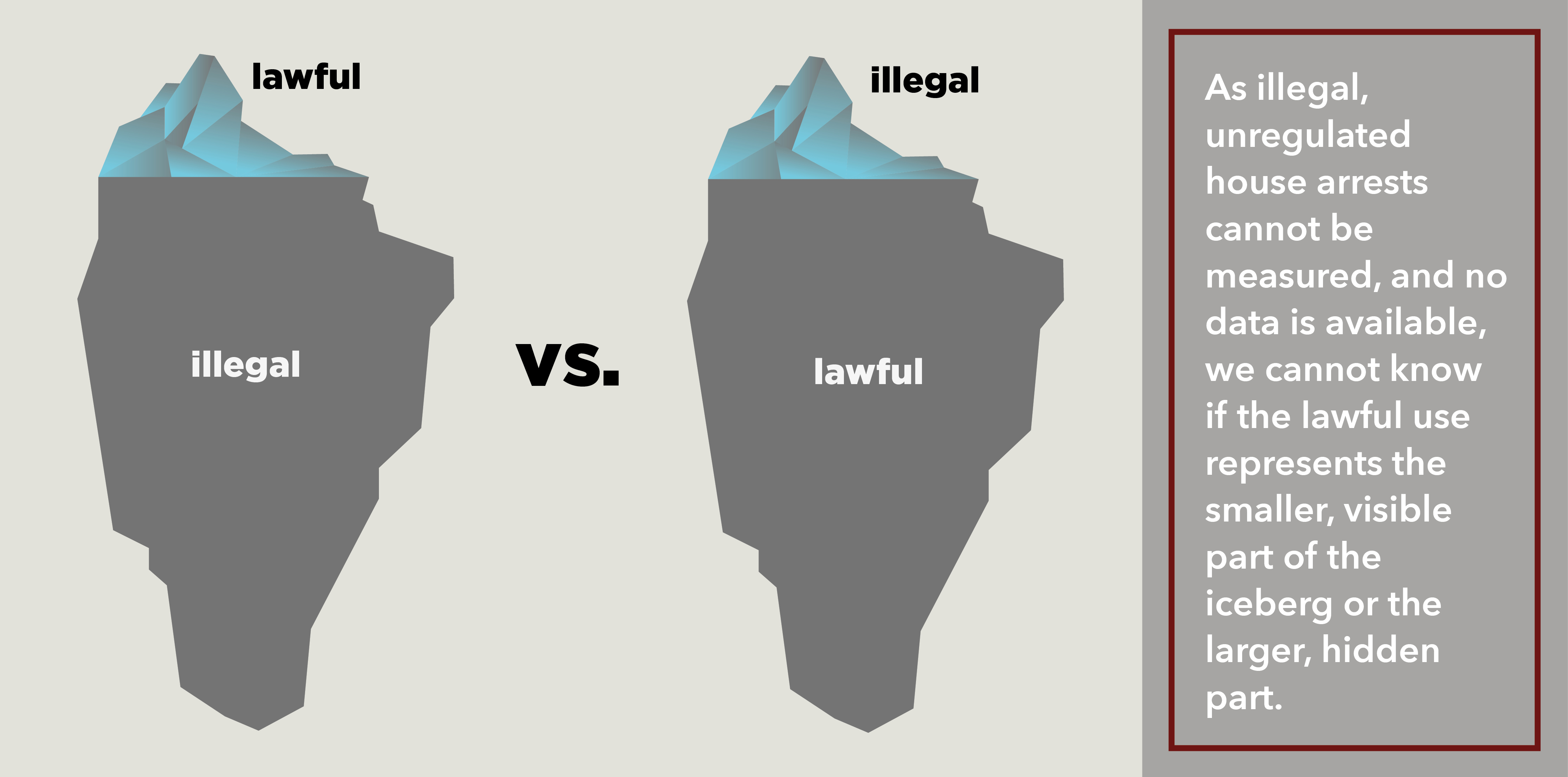

The report also compares the use of house arrests as codified into law with its arbitrary and illegal use by the police. For decades, placing human rights defenders has been a well-established practice, and the lawful use of house arrests accounts for only parts of its total usage. However, there are no official data sets available to estimate the scale of its illegal use.

The report identifies a series of cases of house arrests, both lawful and entirely illegal ones, and the type of situations in which house arrests can and are being used. The report also identifies what government bodies can issue house arrest orders, and how that has expanded within the legal framework following the two major revisions of the Criminal Procedure Law in 2012 and 2018 respectively.

The use of lawful house arrests spans from use instead of detention - as an alternative to release on bail before trial -, and use of house arrests instead of regular arrest or because of ‘special needs’ of the case. In its illegal form, it is often used short-term to block the movement and/or communications of human rights defenders close to ‘sensitive dates’, to keep said defenders under close surveillance and prohibit their work, and/or simply as an alternative to formal detention. In recent years, authorities have also started placing those released from prison into house arrest, as a ways to manage public opinion and ensure minimal attention is paid to them upon their release from prison.