International Day of the Disappeared 2021: China ramps up disappearances

Today, August 30, marks the international day of the disappeared, a day created to draw attention to what is considered one of the worst human rights atrocities in international law – the use of enforced or involuntary disappearances.

Key points

- Disappearances in RSDL and Liuzhi systems alone are likely to reach 40,000 to 50,000 for 2021

- Despite Covid19/Coronavirus China's use of disappearances continued to grow between 2019 to 2020

- China now using at least six forms or methods for enforced disappearances

- The NSC, now tasked, despite being a non-judicial body, with leading China's "international judicial cooperation" stands credibly accused of three to four counts of crimes against humanity, its use of systematic disappearance standing at its core

- The UN and western governments lend legitimacy to both the MPS and China's new NSC by entering into agreements with them without risk assessment nor preparedness

For this year, due to the significant amount of original research and data produced by Safeguard defenders concerning China’s two premier systems for disappearances – the police and Ministry of State Security’s (MSS) use of RSDL (residential surveillance at a designated location), and the National Supervision Commission’s use of Liuzhi (retention in custody)– SD will present a summary of key issues concerning disappearances in China, trends in how these systems are being used, western government’s unintentional support of their growth, and steps needed to be taken to arrest these developments, and importantly, to stop them from spreading to other authoritarian states around Southeast, east and central Asia.

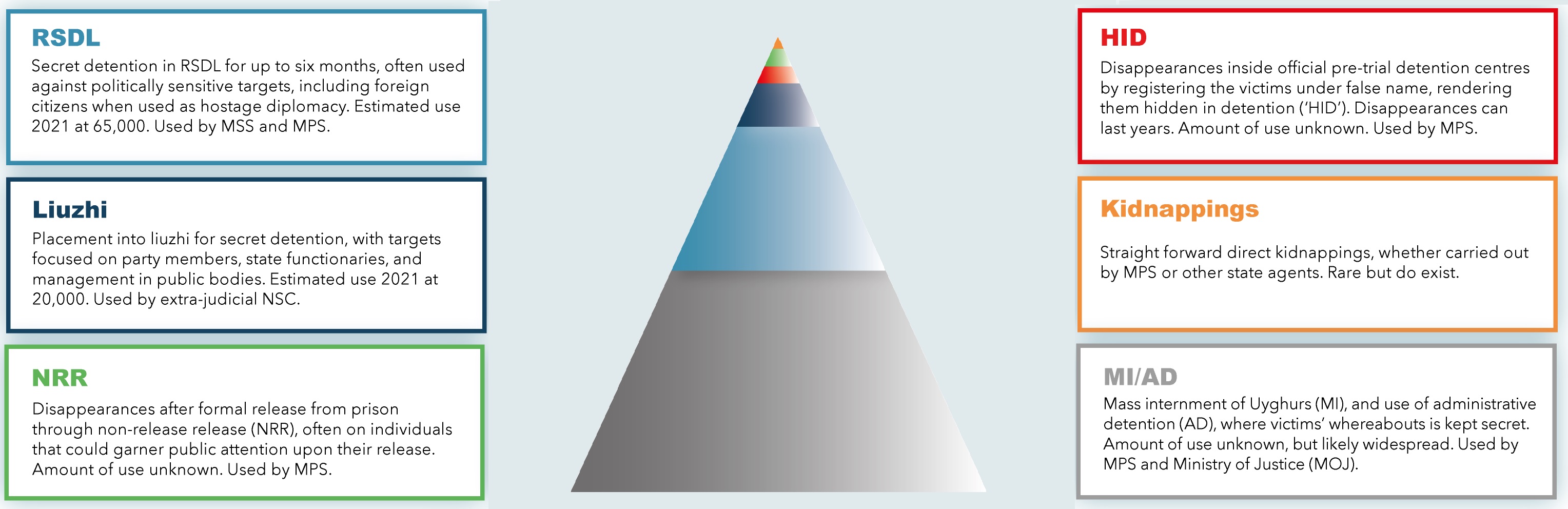

China employs at least six types of, or methods for, disappearances.

*Note: For RSDL use, it should read up to (and including) 2021.

For most of these types, there are no reliable figures or data. However, SD has pursued the use of disappearances by the NSC, and has, using the Supreme Court’s database on verdicts, been able to present ground-breaking data on use of RSDL. However, all other systems and methods above are little studied, and studies that do exist (including three from SD) have not been able to provide statistics on the scale and scope of these systems.

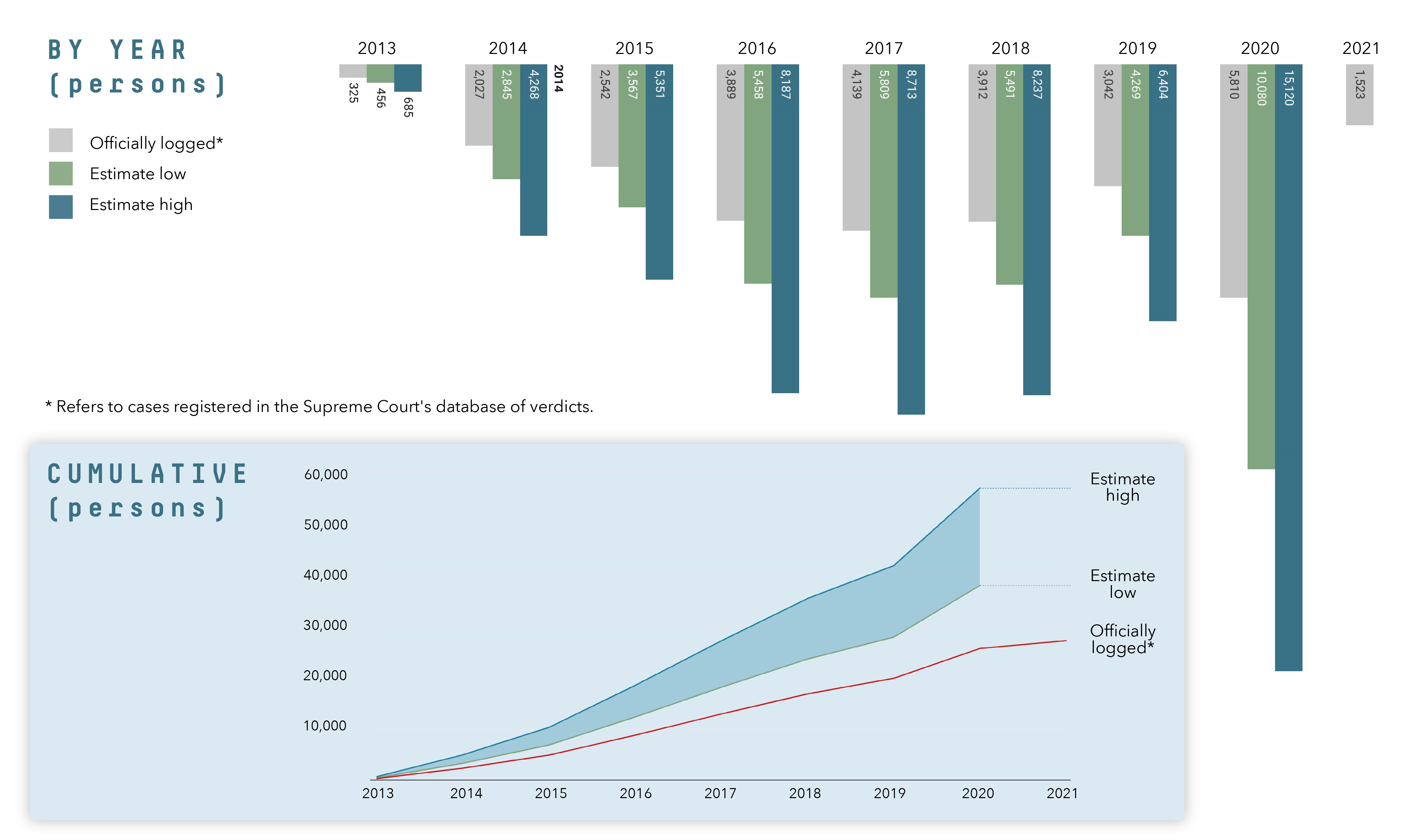

However, for RSDL, for which data has been presented to the UN’s Human Rights Council, twice, including this summer, new data do exist, and the continued expansion of the system, with a particularly strong development between 2019 and 2020, for which initial data indicates will continue for 2021, and is available as part of Locked Up, a graphics-oriented report on the reality of life inside RSDL, and, in more detail, in the evidence submission to the UN’s Human Rights Council.

Most, but not necessarily all, cases of RSDL constitute both an enforced disappearance, but also torture. Access to legal counsel need be denied, and the whereabouts of the victims' placement denied to family, and the person kept incommunicado, for it to count as enforced disappearance. A database of deep studies of individual RSDL cases, currently including near 200 cases, shows only one single victim given access to legal counsel, and only one case where the persons' whereabouts were provided to his/her family. Despite a 2016 regulation that added, in theory, the possibility of prosecutorial oversight of people's treatment inside RSDL, SD has yet to encounter a single case with any such weekly visits. The reason is likely that the Prosecutor may perform weekly visits, not should, and also that police and MSS, the two users of RSDL, can deny such visits without having to give justification beyond that it may 'impede' their investigation.

Inside RSDL, the use of torture appears common, as the below table shows. In addition, the UN has, both via General Assembly reports and by the Special Procedure on Torture established that prolonged use of solitary confinement for investigation purposes constitutes both torture and maltreatment (articles 1 and 16 respectively in the Convention Against Torture). As all those placed into RSDL must by law be kept in solitary confinement, all use of RSDL constitutes torture.

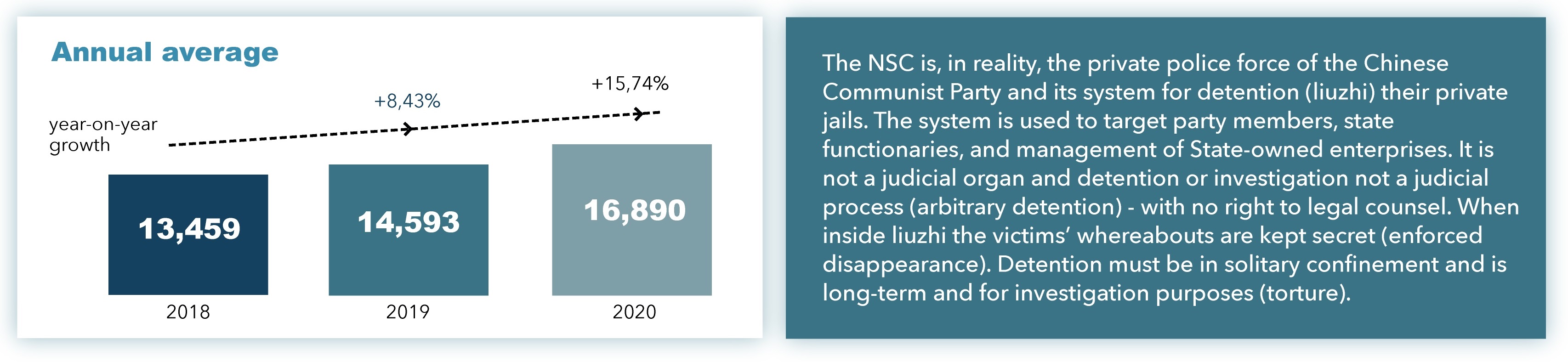

Even though it is our understanding that RSDL is likely to overtake Liuzhi as the most commonly employed system for disappearance soon, primarily due to significant growth in the use of RSDL by local police, having been gradually made aware of how powerful a tool it is, after initially being used primarily by higher-level police against ‘political targets’, existing data would indicate that Liuzhi, as of 2020, remains slightly more used. However, increased growth in Liuzhi use – which is used exclusively by China’s new National Supervision Commission – is also expected.

Between 2018 (the first year Liuzhi was in operation) and 2019 saw little growth, but between 2019 and 2020, it jumped up by over 15%. As the NSC is ‘settling in’, and local NSC bureaus start following the lead of the higher-level bureaus, there is no reason not to expect continued growth in Liuzhi use.

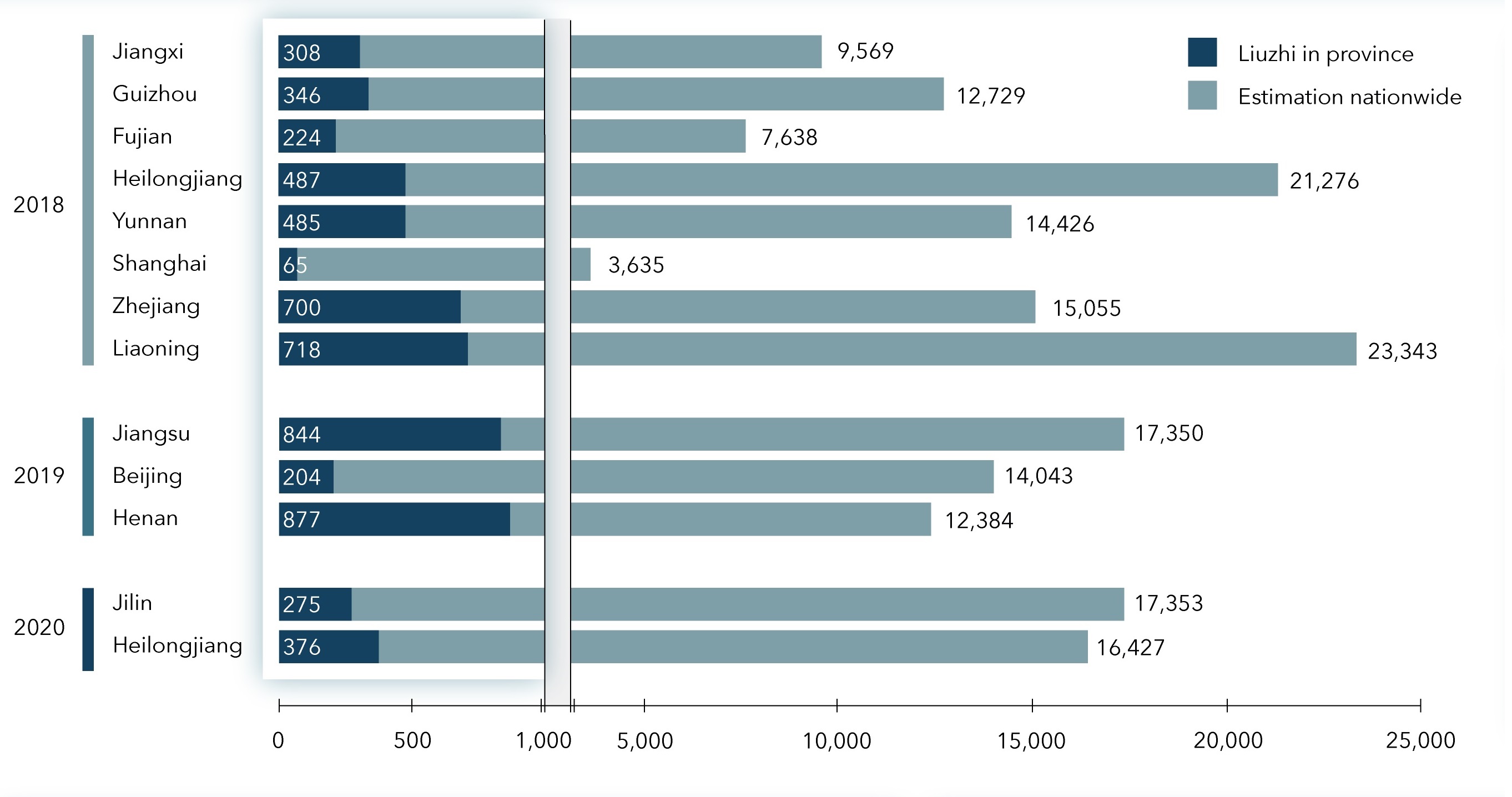

As of mid-2021, based on an evidence submission to the Human Rights Council by SD, drawing on the scarce information made available by the NSC (CCDI), for a few select provinces, SD estimates the current scope and scale of Liuzhi to be:

As of mid-2021, based on an evidence submission to the Human Rights Council by SD, drawing on the scarce information made available by the NSC (CCDI), for a few select provinces, SD estimates the current scope and scale of Liuzhi to be:

For placement into Liuzhi, which is not a judicial process, there is no right to legal counsel at all. As with RSDL, placement can last up to six months, must take place in solitary confinement, in facilities not run by the judicial system. Informing the family of the victim of their whereabouts is, like with RSDL, voluntary. Hence, placement in Liuzhi can and often do constitute an enforced disappearance, always constitute torture, but is also, by any definition, an arbitrary detention. There is no method to appeal placement into Liuzhi within the judicial system as it, as stated, is not a judicial process. The NCS has been classified as a non-administrative body, which gives it immunity from the use of administrative law to challenge any illegal behavior. Its staff is also not classified as “judicial personnel,” which removes some of the protections that, even if only on paper, exist against the use of torture. The NSC, in many ways, is RSDL on steroids.

For placement into Liuzhi, which is not a judicial process, there is no right to legal counsel at all. As with RSDL, placement can last up to six months, must take place in solitary confinement, in facilities not run by the judicial system. Informing the family of the victim of their whereabouts is, like with RSDL, voluntary. Hence, placement in Liuzhi can and often do constitute an enforced disappearance, always constitute torture, but is also, by any definition, an arbitrary detention. There is no method to appeal placement into Liuzhi within the judicial system as it, as stated, is not a judicial process. The NCS has been classified as a non-administrative body, which gives it immunity from the use of administrative law to challenge any illegal behavior. Its staff is also not classified as “judicial personnel,” which removes some of the protections that, even if only on paper, exist against the use of torture. The NSC, in many ways, is RSDL on steroids.

As the system is used primarily against party members, State functionaries, and leadership within public bodies, whether State-owned enterprises, universities, hospitals, “labor unions” etc., the victims rarely elicit sympathy and both foreign governments, the United Nations system, and international media rarely pays attention. Those in Liuzhi are simply left to their own devices.

That the NSC is not a judicial body, and is credibly accused of multiple counts of crimes against humanity did not stop the UN agency UNODC to sign an MoU with the NSC, an MoU that UNODC has refused to provide a copy of to SD nor to media that has inquired. UNODC, as well as several countries that have signed MoU’s with the NSC, is actively providing legitimacy to the NSC in international judicial cooperation, despite the fact that the NSC is not a judicial body, and that it is engaged in mass use of disappearances, arbitrary detention and torture. This also includes a small number of western nations, such as Denmark and Australia.

Looking at the data available for both RSDL and Liuzhi, and trying to estimate its use in the near future, paints a dim picture.

Taken together, RSDL and Liuzhi alone, not considering any of the other four methods of disappearances, would thus, in 2020, be responsible for up to 30,000 disappearances and use of torture, and more than half of those constituting arbitrary detentions. By 2021, it would be remarkable if that figure did not grow to the 40,000 to 50,000 range.

How many in Xinjiang’s camps are held incommunicado and without family members notified of their whereabouts is entirely unknown. Likewise, how many are currently held in China’s official pre-trial detention facilities, locked away under false names and therefore disappeared, is not only unknown but there is so little data that no estimate of any kind is feasible (Full report, China’s Vanishing Suspects, here). The same can be said for those disappeared upon release from prison into ‘non-release release’, often taken away by police and placed into incommunicado house arrest at a secret location (Full report, China’s False Freedom, here), or for that matters, those simply taken away without any pretense of law whatsoever, in the most ‘traditional’ type of kidnapping.

New developments and threats

Wenshu, the database on verdicts from Chinese criminal courts run by the Supreme Court, has since its inception in 2013 been marred with problems, and estimates put the number of verdicts uploaded and made public at, at best, roughly half. However, starting 2021, there have been at least two rounds or campaigns to purge records from the database, in a significant setback to transparency and for the ability of outside scholars and entities such as SD to be able to study these issues. One report noted that many ‘freedom of speech’ verdicts disappeared overnight, while other reports have taken note of the shrinking number of verdicts the database now holds.

It is possible that the data secured in the first half of 2021 will be the best and most complete (yet very incomplete) data that entities outside of the Chinese government will have to work with. This would represent a significant setback and add more opaqueness to the Chinese criminal justice system.

Due to RSDL having failed to spark neither outrage, condemnation, nor close study, and the same now happening with Liuzhi, it is a very real possibility that other authoritarian governments in Southeast-, South- and Central Asia paying attention to this lack of pushback against the erosion of one of the key human rights protections, and deciding to implement similar systems. Failure for many years to organize any pushback against China’s then growing use of forced televised confessions before trials – a mockery of the very idea of a fair trial - first studied and exposed by SD in its report Scripted and Staged, and later its book Trial By Media, seems to have influenced the Vietnamese government to copy and ape China, the latter whose use of such confessions was reported on by SD in its report Coerced on Camera. Likewise, China’s brazen kidnapping of foreign citizens, and the limited pushback against that, certainly was key for Vietnam to dare carry out a similar kidnapping, in broad daylight, in central Berlin.

How long before disappearances, among any authoritarian governments’ most potent weapon against dissident and civil society, becomes “legalized” or put into systematic use in other countries? And if so, how many countries can adopt disappearances before it puts the international human rights system at the breaking point? How many disappearances need to take place until the norm against disappearances erodes?

Countering China’s expanded use of disappearances

- Crimes against humanity

Even though China is not a party to the Rome Statute (International Criminal Court), international customary law largely recognizes its definition of crimes against humanity. The violations herein outlined, from disappearances to unlawful/arbitrary detentions to torture, are supported by data so credible that it can no longer be ignored. In addition, there is now enough evidence that shows that, at least within RSDL and Liuzhi, its use is either systematic or widespread – the needed level to declare it a crime against humanity. Indeed, at tens of thousands of victims annually, it is both systematic and widespread. The relevant UN organs need to launch full inquiries based on evidence submitted, and foreign governments need to start addressing these issues as crimes against humanity, and place them at the top of the agenda at bi- and multilateral dialogs.

- Sanctions

Canada, the European Union, the UK, and the US need to take a multilateral initiative to issue Magnitsky sanctions against the top commanding officers responsible, targeting the leadership of the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security, and the National Supervision Commission. Failure to sanction these commanding officers would significantly weaken Magnitsky sanctions regimes, as the abuses are so widespread, and would, like labeling these violations as crimes against humanity, send the strongest possible denouncement of this practice, and incur both political and real costs on the perpetrators.

- Stop legitimizing the organs responsible

The continued existence of extradition treaties with China, even after many western nations have suspended those with Hong Kong, is an affront to the rule of law. It also sends mixed signals, allow China easier access to pursue “fugitives” abroad. However, there are many other levels of international judicial cooperation, and related agreements need to be analyzed on a case-by-case basis, bearing in mind that even less significant agreements can encourage the responsible bodies, primarily the MPS. There are many instances where such agreements primarily benefit China, in addition to lending legitimacy to the bodies involved, even as the parties concerned are actively engaged in the mass use of disappearances.

This is of particular concern regarding the National Supervision Commission, which has been given a lead role in managing China’s international judicial cooperation, including reclaiming “fugitives”. The NSC is not a judicial body, and no cooperation, of any (judicial) kind, should be entered into with it. Despite this, the UN agency for corruption and cross-border crime, UNODC, has done exactly that, and so have organs of the State in Denmark and Australia, along with over 80 other countries. For each one, even in merely signing non-operational type MoU’s, legitimacy is given to a body responsible for China’s transnational repression, and crimes against humanity in China. For each treaty entered into, the MPS or NSC gains legitimacy and gets placed in a better position to sign yet further agreements, including extradition treaties. For each signed agreement, the signatories help weaken the rule of law and the international rules-based order.