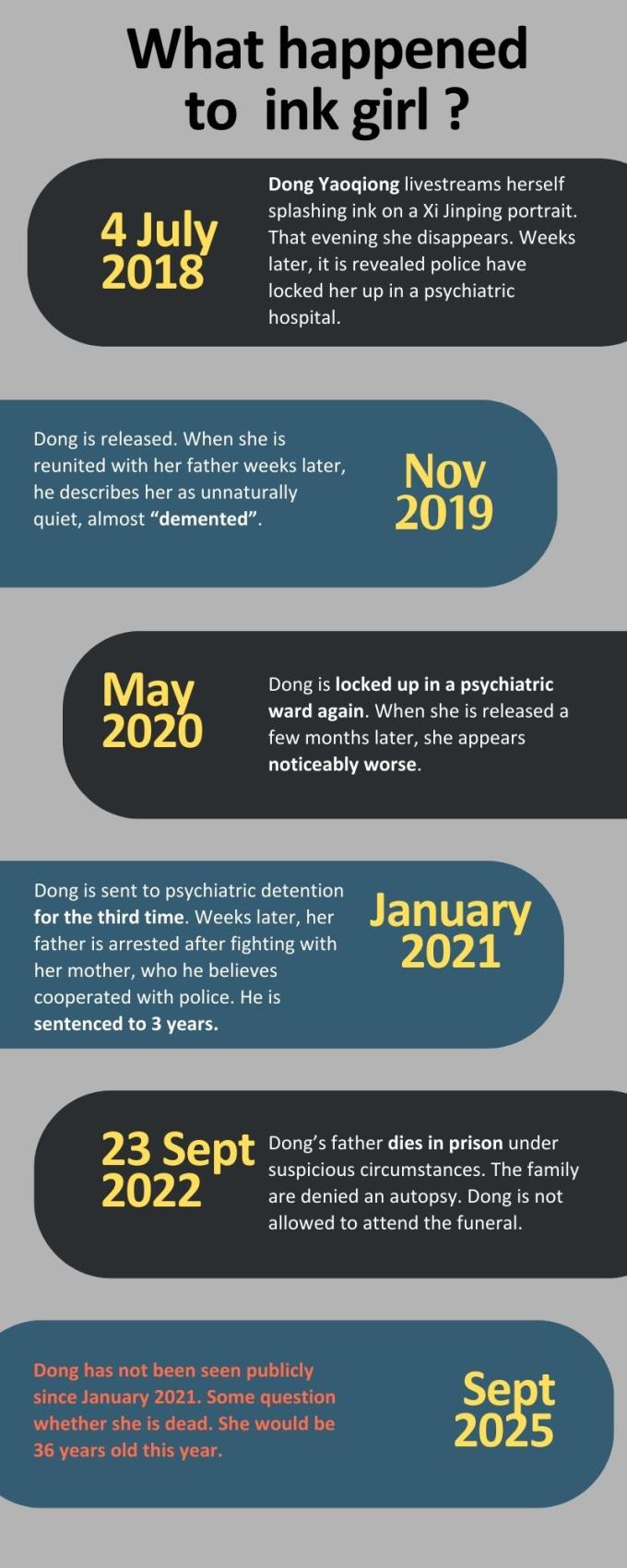

A letter to Dong Yaoqiong—China’s disappeared ‘ink girl’

In the summer of 2018, a young woman splashed ink on a poster of Xi Jinping in Shanghai, sparking a tragic chain of events that have left at least two people dead and another disappeared, presumed dead.

Dear Dong Yaoqiong,

We’ve never met, but we have followed your tragic story and that of your father over these last seven years.

Today is 23 September 2025, three years after your father died in prison, his body covered in wounds and bruises. He was just 54 years old.

At the time, we read that you might not have even been told that he had died.

Perhaps, even, that he was in prison at all.

And then last year, rumours began circulating among rights defenders, your friends and family members, that maybe you too had died.

No one had heard from you since January 2021. That was when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) forcibly locked you up in a psychiatric hospital for the third time.

We looked up that hospital—Zhuzhou City Hospital No. 3. From the image on its website, it has a modern façade with gleaming windows, but we know from the testimony of many others who have been forcibly committed to mental institutions by the CCP that what goes on in the psychiatric detention ward is cruel, frightening and inhumane.

To this day, the CCP still uses psychiatric detention on their perceived enemies – petitioners fighting injustice in their villages, activists speaking out for freedom and rights. It is one of the most chilling ways the CCP uses to disappear critics – forced hospitalization in a mental facility without medical justification. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of victims.

We documented it all for our report—Drugged and Detained: China’s Psychiatric Prisons. We described how people with absolutely no medical reason are belted to their beds and left to lie in their own waste for hours; how they are subjected to excruciating electroshock therapy without anaesthesia leaving them traumatized and crushed; and how they are force fed drugs that render them unable to think or feel.

There are no visitors or phone calls home. They are locked up – just like you—for months and years at a time. If they are released, and don’t stay silent, they go back, again and again.

They have no way to be let out. They have no way to ask for help.

It's now been more than four and a half years since you disappeared. According to China’s own law (Civil Code, Article 46), theoretically, you could be declared “presumed dead”.

Two years ago, during Grave Sweeping Festival (Qingming), when friends went to pay their respects at your father’s grave, your uncle said that you were most likely already dead. Your cousin added that they thought you had been dead for a while now.

We have tried to find out what happened to you—enquired through all the possible channels—but in the current tight controls on information in China, when people are too scared to talk, we can’t find any leads.

You have simply disappeared.

You gained notoriety more than seven years ago when you splashed black ink on a poster of Xi Jinping in Shanghai, streaming it for all the world to see on 4 July 2018. At a time when the CCP does not suffer any criticism, this was a truly courageous act. We believe you accomplished something which many longed in their hearts to do yet did not dare.

Overnight, you became famous. Did you know the world started calling you “ink girl” after that?

The video of that morning still exists, although its quality is grainy. We see a young woman, with long dark hair, and wearing a yellow t-shirt with the words “New York, New York” printed on the front. You speak firmly into the camera. You tell us it’s around 6.40 in the morning, then swing the lens round to show us a high-rise building in the background – it’s the HNA tower in Shanghai. Then you stand in front of a wall with a large Xi Jinping poster and your tone becomes more serious.

“I oppose Xi Jinping’s dictatorship, autocracy and tyranny. I oppose the Chinese Communist Party’s brain-control oppression against me!”

And then you walk over to the wall and from what looks like a red plastic jug you splash black ink over Xi’s face, while saying: “I hate him to the bone.”

That night police came to your home and disappeared you into psychiatric detention.

There’s not much about your life online before that day in July 2018.

You were born in 1989, the year the CCP killed thousands of protesters in the Tiananmen Square crackdown. You grew up in a small town, Tianshui, in the central province of Hunan. Sometime in your twenties you moved to Shanghai and got a job in real estate.

As the eldest daughter in a traditional Chinese family in the countryside, maybe you didn’t receive the attention you deserved. Without freedom of speech, your life in China may have been frustrating and limiting. But to this day, we cannot guess what made you film yourself splashing ink on Xi's portrait that day. To do something so risky, we believe you must have felt desperate.

Did you know you would pay such a high price?

We like to imagine that you would be cheered by all the copycat videos and photos of posters of Xi similarly defaced that surfaced on the internet days after your performance art. Some smeared the Chairman’s face with mud; others stained him with paint.

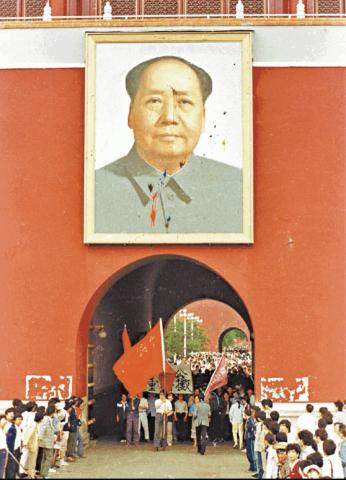

In the eyes of the CCP, desecrating portraits of the leader has always been regarded as a serious offence. The year you were born, three young men from Hunan travelled to Beijing to join the protests in Tiananmen Square. They threw paint and ink at Mao Zedong's portrait that hangs on Tiananmen Gate, an act for which they paid dearly. One of them, Yu Dongyue, was sentenced to 20 years in prison. As a result of prolonged solitary confinement and abuse, he developed schizophrenia.

His fate foreshadows your own harsh treatment.

We wonder if you would be cheered by those who campaigned for your release in the months and years after your first disappearance. Activist painter Hua Yong and rights defender Ou Biaofeng spoke up for you. With great sorrow, we have to tell you that Hua, even though he fled into exile to Canada, died under mysterious circumstances. Ou was sentenced to three and a half years in prison on charges of “inciting subversion of state power”, in part because he would not keep quiet about your case. He was released a year ago.

Your father, Dong Jianbiao, never stopped fighting for you.

He tried many times to get the hospital to release you. He lost his job as a coal miner because he would not keep quiet.

And when more than a year later in 2019 they allowed you home, he wrote how you had changed into a different person. His once lively daughter was now almost catatonic.

“She basically doesn’t talk at all,” he said. “I think she seems to have some symptoms of dementia. When I asked her about what had happened before, she just wouldn’t say a word.”

It wasn’t long before the CCP locked you up in the psychiatric ward again and when you were released for the second time your father said you appeared worse. You would scream and scream and sometimes lose control of your bladder. He saw how the hospital had broken his daughter.

By the end of the year you had uploaded a new video complaining how you had no freedom, that your life was under close surveillance by the authorities, and that you were unable to contact your father or friends. You said that you had been compelled to write a pledge and that you had been assigned to work in a government agency. Even under such intense pressure, you still yearned to fight for your freedom.

Towards the end of that video your eyes filled with tears and we could see your pain. You were still that brave and beautiful girl.

Weeks later, the CCP sent you back for the final time to the psychiatric ward.

And that’s the last we ever heard from you.

Desperate and heartbroken, your father went to your mother to plead for her to help him get you out. He believed she had cooperated with the police to send you back. He threatened to burn her house if she didn’t help. Tragically, he was arrested and sentenced to three years in jail.

On 23 September 2022, three years to the day today, your father died in prison under suspicious circumstances. Family members were not allowed an autopsy, although his body was bruised and battered. The authorities forced your younger brother to sign a form authorising the cremation of your father's remains, the day after he died. This was in contravention of Chinese tradition, which observes a three-day period of repose.

The funeral was rushed through in a matter of days and the day of the ceremony, the road leading to your home was cordoned off by the authorities and human rights activists who tried to attend were threatened or detained.

You were not even allowed to attend the funeral of your own father.

It’s been three years since your father’s death. And almost five years since you disappeared.

To this day, we cannot believe that you are dead. But however hard we try we cannot find any evidence to prove or disprove it.

We write this letter as a promise that we will not forget you, and we hope by publishing it, that the world will not forget you either.