Why does China keep disappearing female reporters?

Minnie Chan Man Li (陈敏莉), a senior reporter for the Hong Kong-based newspaper South China Morning Post (SCMP) has been missing in China for more than one month.

If this was almost any other country, your first thought might be she had been in an accident or had been attacked.

But in China, the most likely answer is that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has disappeared her for political reasons.

Previous examples point to the likelihood that she is now in a secret jail system called Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). See our report on life inside RSDL here.

In recent years, the CCP has secretly detained a number of female journalists.

In the summer of 2020 they grabbed Cheng Lei, an Australian business news anchor for state TV station CGTN.

Four months later Chinese journalist Haze Fan, who worked for Bloomberg, also disappeared into the CCP’s secret jail system.

According to Al Jazeera, another female reporter who worked at SCMP disappeared in China for possibly up to nine months last year. The Qatar-based media gave no further details and did not name her for reasons of privacy.

Of course, it’s not only female journalists. The CCP has a growing habit of disappearing anyone for political reasons.

But if indeed they have detained her, then she will be the fourth female reporter to be disappeared in just the last three years.

29 October: Minnie Chan is in Beijing to report on the three-day Xiangshan Conference, an international security forum.

31 October: The conference ends.

1 November: She shares her SCMP articles on the conference on Facebook and LinkedIn.

11 November: She posts some images of two young girls to her Facebook. This post is not typical of the vast majority of her previous entries, which are links to news articles. Comments from friends left underneath query whether the post was made by her.

She has made no further posts as of publishing this article.

30 November: The news of her disappearance breaks.

The first report that she is missing appears in Japan’s Kyodo News, which says some of her friends are worried she “may be under investigation by mainland authorities.”

1 December: The Hong Kong Journalists Association release a statement saying it is “deeply concerned” about her disappearance and appeals for information on her whereabouts.

SCMP, which must have known of Minnie Chan’s disappearance weeks ago since she did not return to work, begin to respond to media questions:

They tell Kyodo News that she is "on personal leave”.

They tell the Hong Kong-based, Chinese-language newspaper Ming Pao that “her family has told us she is safe but requested that we respect her privacy.”

They tell RFA that she is "on vacation," and to “respect her privacy”.

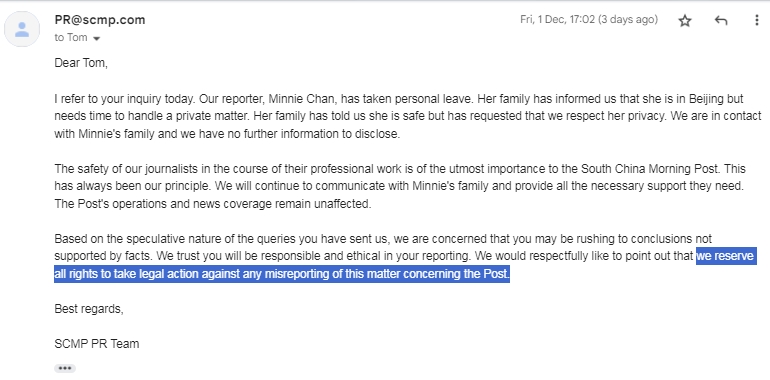

But when Hong Kong Free Press (HKFP) send an emailed request to SCMP for comment, their response is extraordinary.

The SCMP repeat the line they have told other media – that she is safe and her family wish them to respect her privacy. But then they end with a threat that they “reserve all rights to take legal action against any misreporting of this matter concerning the [SCMP].”

HKFP added that this hostile reply came hours after the requested deadline. This suggests that the SCMP had spent considerable time mulling their response to what they claim is simply a staff member on leave.

These caged responses from SCMP are not what you would reasonably expect if Minnie Chan was simply “on vacation”.

“They are safe and well but wish for their privacy to be respected.”

Where have we heard these words before?

In 2021, Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai disappeared after she accused a high ranking Chinese official of sexual assault.

The International Olympic Committee were allowed a video call weeks later in which she said: “she is safe and well… but would like to have her privacy respected.”

Minnie Chan is a veteran journalist, with almost three decades of experience.

Minnie Chan is a veteran journalist, with almost three decades of experience.

According to her SCMP profile page, she has been writing for the paper since 2005.

Her beat is a politically-sensitive one in China; her profile goes on to say she is an “award-winning journalist, specialising in reporting on defence and diplomacy in China.”

Online media Asia Sentinel even speculated that her coverage of military news in China might mean she has been caught up in the "turmoil" at the top of the People's Liberation Army. In August 2023, then Defence Minister Li Shangfu disappeared. Just a week before Minnie Chan also disappeared, Beijing announced he had been dismissed from his post.

According to her LinkedIn page, before 2005 she worked for a number of other Hong Kong media, including TV stations and Apple Daily, a now shuttered newspaper that was highly critical of the CCP.

On social media, she has posted some critical commentary of Beijing. For example, in 2019, she made fun of pro-China protesters in Hong Kong while the anti-extradition law demonstrations were in full swing. When her former employer Apple Daily was forced to shut down by the Hong Kong police in 2021, she wrote that it was being "strangled by powerful interests."

The secrecy surrounding such disappearances and legal proceedings makes it often impossible to understand why someone is targeted in China.

Cheng Lei was accused of “supplying state secrets”, while Haze Fan’s alleged “crime” was of “endangering state security”. Cheng Lei, who was only freed a few months ago, says she had been punished because she broke a news embargo by a “few minutes”. Haze Fan was released on bail last year, but there has been no news of her since then.

RSDL is a powerful tool used by the police to primarily coerce confessions and break people’s spirits while a case is “built” against them.

It is China’s system of state-sanctioned kidnapping, legalised in 2012, that it is using against thousands of people every year.

The system, which has been condemned by the UN as tantamount to enforced disappearances, allows for up to six months detention in a secret location where the prisoner has no access to the outside world. And that includes a lawyer, never mind a family member.

They are typically confined to a room, with no access to sunlight, and under 24-hour surveillance, which includes being watched while asleep and going to the bathroom. In such conditions, RSDL detainees are under extreme risk of physical and psychological torture.

RSDL is often only the beginning.

Once it is over, the prisoner is usually transferred to detention and is then formally arrested, where they may wait years for a trial and sentencing. Lawyer access even then is frequently barred, sometimes with the use of fake names in detention.

Cheng Lei, the Australian journalist, who was disappeared in the summer of 2020 and was kept in RSDL for the full six months said it was like “being buried alive.”

Safeguard Defenders has spent years documenting abuses in RSDL. Our report Locked Up: Inside China’s Secret RSDL Jails is a graphic-heavy publication that takes a deep dive into the daily horror of what it is like to be in RSDL.