China’s criminal justice system in the Age of Covid

This is the first in a series of small investigations and larger reports that look at changes in China’s criminal justice system and human rights since COVID-19. This article is best read as a PDF report, click here to download, and the graphics are not suitable for reading on mobile devices.

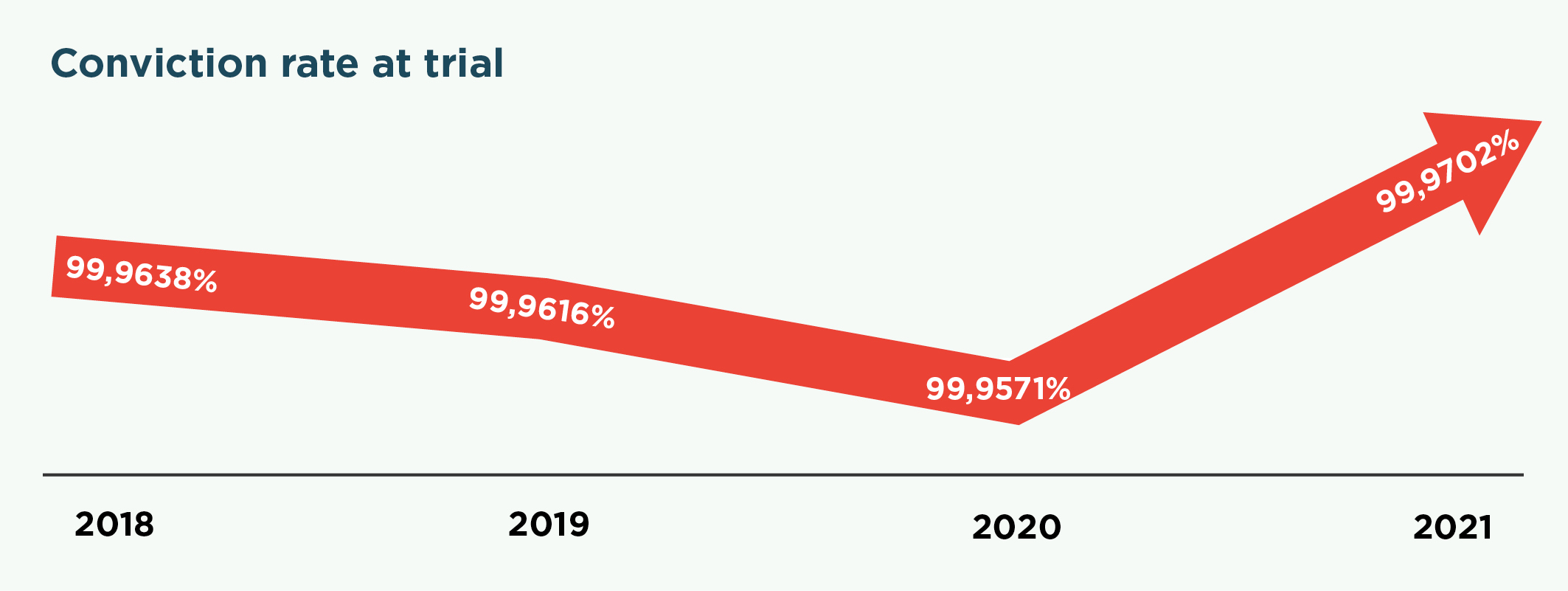

The rate of guilty verdicts in Chinese courts reached a record high last year of over 99.97% while the number of trials has trippled over the last two decades, according to a new investigation by Safeguard Defenders using official government data.

The rate of guilty verdicts in Chinese courts reached a record high last year of over 99.97% while the number of trials has trippled over the last two decades, according to a new investigation by Safeguard Defenders using official government data.

We got a glimpse into changes to the China’s criminal justice system during 2020 and 2021 under COVID-19 following the release of work reports from the Supreme Court (SPC), the Supreme Procuratorate (SPP) and the Party-organ Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) amongst others after the conclusion of the National People’s Congress in March.

Last December, Safeguard Defenders released a major report, Access Denied 3: China’s Legal Blockade, on how detention centres are preventing lawyers access to their clients and how this practice has become more serious under COVID. This investigation however looks at basic quantitative data on changes to rates of arrests, prosecutions, trials and sentencing.

Using official data, this investigation compares the two pre-COVID years of 2018 and 2019, with the COVID years of 2020 and 2021. A major report, tentatively called Covid in China - When Endemic Repression meets Pandemic, is forthcoming late this summer.

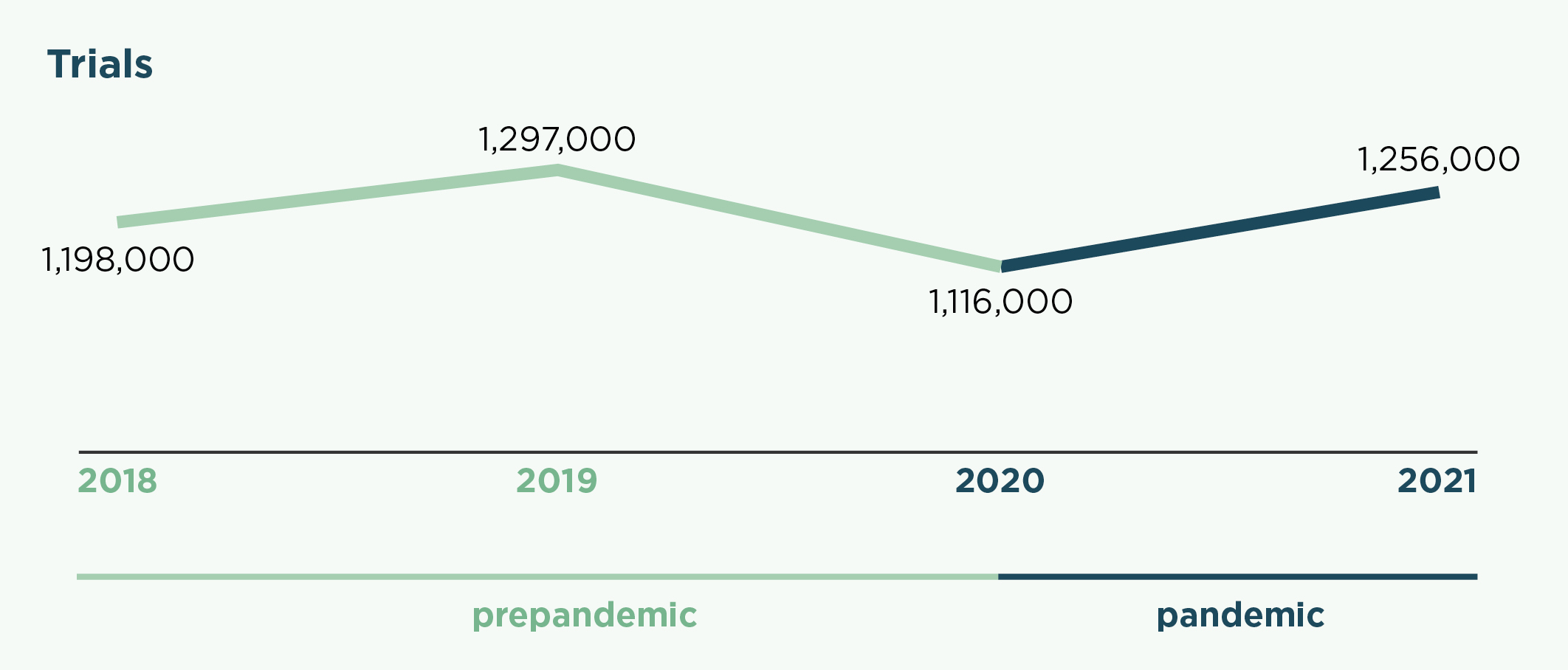

Trials and sentencing

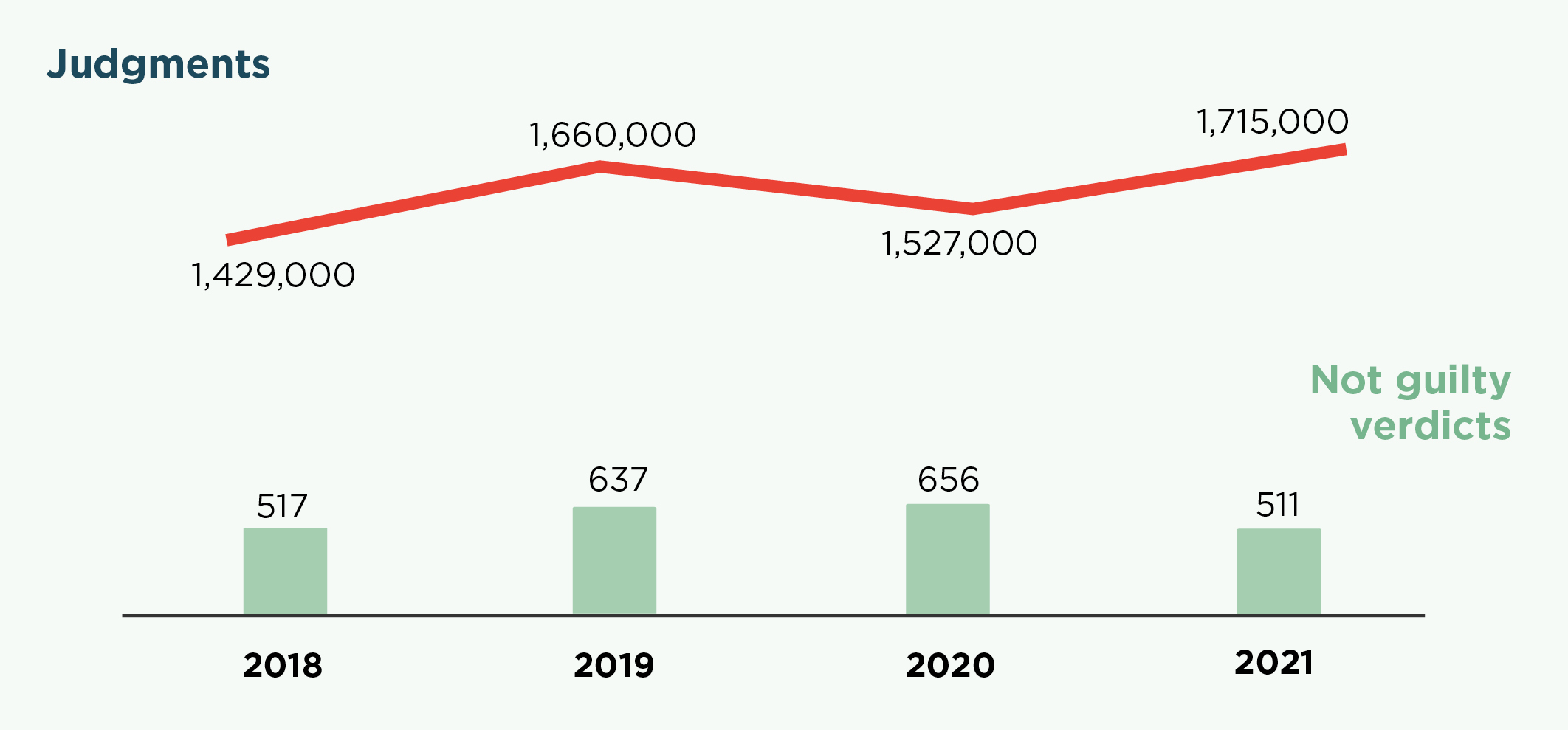

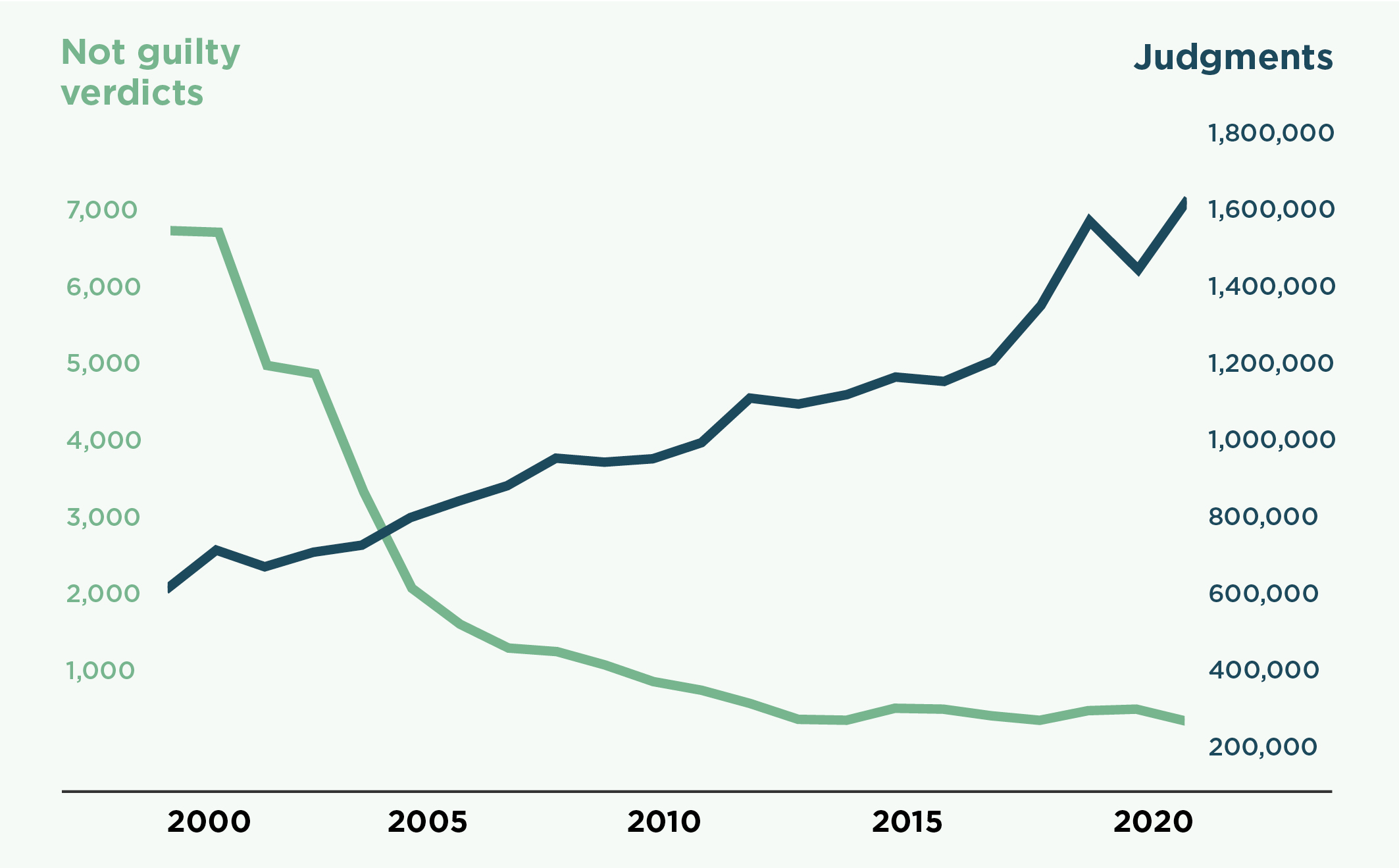

In 2021, over 99.97% of criminal trials at first instance resulted in guilty verdicts, a record high since 1980 when data was first recorded. Likewise, the number of not guilty verdicts continued to plummet, to a record-breaking low of only 511 last year - this compared with more than 1.715 million judgments made.

The number of trials at first instance saw a small decline in 2020 to 1,116,000, but by 2021, it had almost bounced back, reaching 1,256,000, very near the previous record high of 1,297,000 in 2019.

As recently as 2000, China recorded only about 650,000 criminal trials per year, yet had more than 6,000 not guilty verdicts. The number of not guilty verdicts is now less than 10% of what it was in 2000, despite a near tripling of the number of trials between 2000 and 2021.

A comparison of the number of judgments and not guilty verdicts pre- and post-pandemic shows the following.

Historic data shown below tracks the number of not guilty verdicts at criminal trial (at first instance) since 1980, four years from the end of the Cultural Revolution. In the early years, there was considerable yearly variation in conviction rates and the number of people declared not guilty. However, after Xi Jinping took power in 2012, there has been very little variation – and a new normal of extremely low not guilty verdicts has been established with 2021 a record year.

As with arrests, prosecutions and trials, the number of sentences issued saw a small reduction in 2020 at 1,527,000 compared to 2019’s 1,660,000, but recovered in 2021 with a record number of sentences issued at 1,715,000. For more on methodology and related data please see Safeguard Defenders’ earlier investigation, Presumed Guilty (2013-2020).

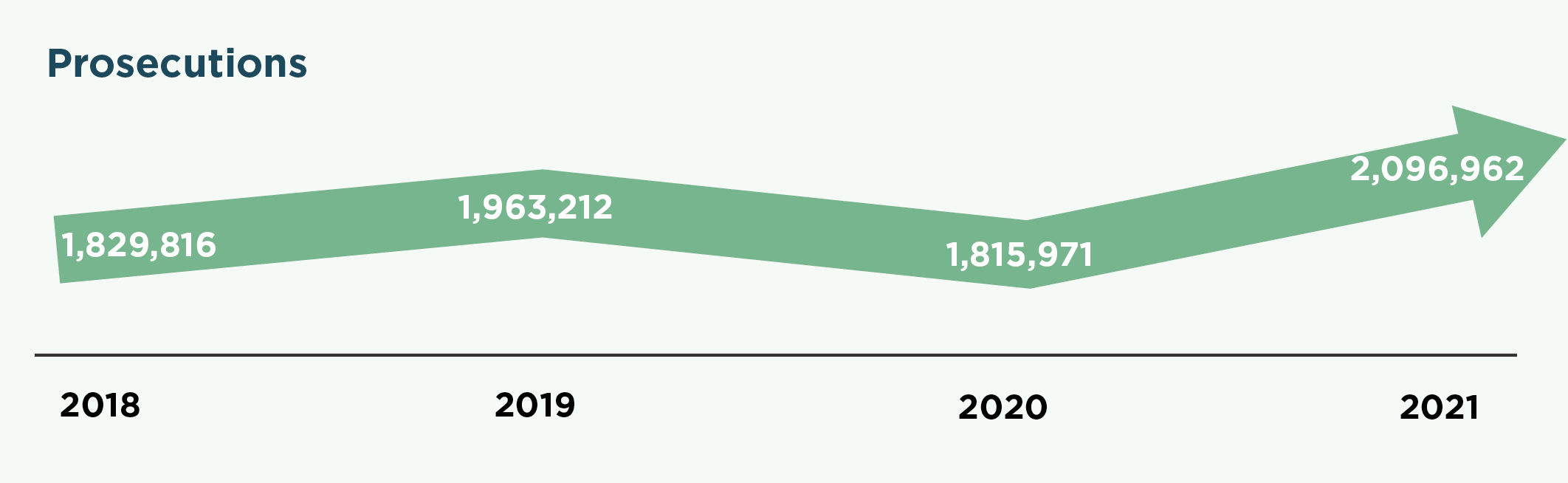

Prosecutions

In the first year of COVID, 2020, there was a steep decline in prosecutions compared with previous years but in 2021 this made a recovery. The changes 2018 to 2021 are as follows.

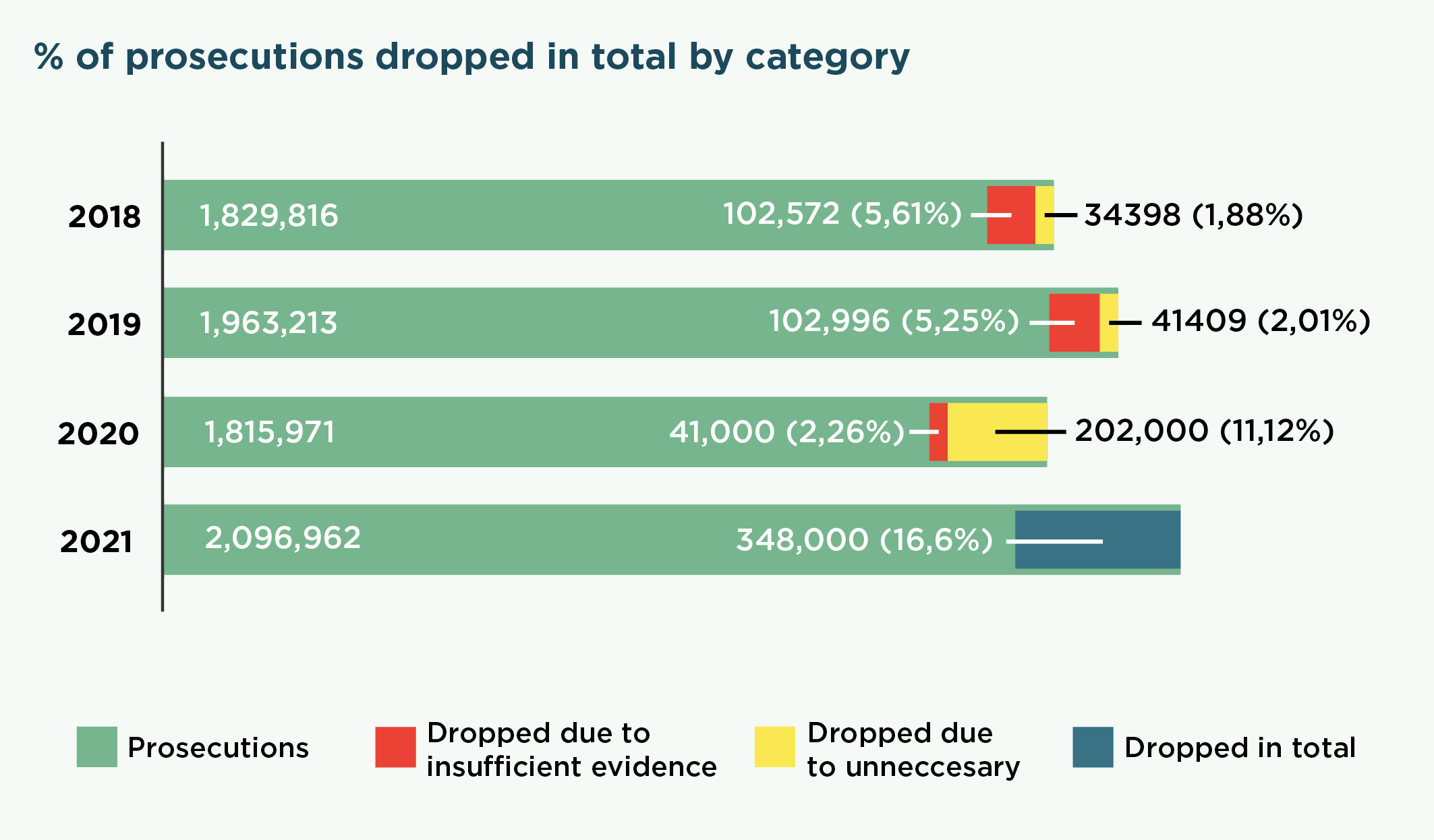

Presumed Guilty drew on two official work reports (Supreme Court (SPC) and Supreme Procuratorate (SPP)) on another key aspect of the criminal justice system – namely how often are cases dropped by the prosecutor after formal arrest. Formal arrest is considered the most important step for any criminal investigation.

The prosecutor can drop a case for two reasons: because of insufficient evidence or because prosecution is deemed unnecessary. The former reason is a fairly important one if the individual is charged with a serious crime, while the second reason is most often used to drop non-serious cases.

In 2020, prosecutors abandoned cases that had been approved for arrest due to insufficient evidence in only 2.26% of cases. This is a significant drop compared with 2018 (5.61%) and 2019 (5.25%). Going back to 2013, that percentage varied between 3.69% and 4.44%. There is no data for 2021 (see below for explanation).

However, cases dropped for being unnecessary to prosecute rose dramatically in 2020, almost certainly due to COVID restrictions shutting down some of the legal system in the spring as China undertook measures to stop the spread of the virus. Some 202,000 cases were dropped, compared with 41,409 for 2019, a year-on-year jump of 393%.

Combining both reasons, some 243,000 cases, or 13.38% of all prosecutions, were dropped in 2020. In 2021, the total combined number was 348,000, or 16.6% of all prosecutions. Safeguard Defenders believes it is highly likely that most of the 348,000 dropped cases in 2021 were because they were deemed unnecessary. However, the work reports no longer provide separate figures. This is a concerning development and prevents analysis in the future on this key metric.

The graph below shows prosecutions initiated and prosecutions dropped for the two different reasons 2018-2021.

It is very likely these 2020 and 2021 figures will revert back to earlier levels, regarding the amount of cases dropped because of insufficient evidence versus unnecessary once the pandemic control measures and limitations to the ability of courts to process cases returns to normal.

Arrests

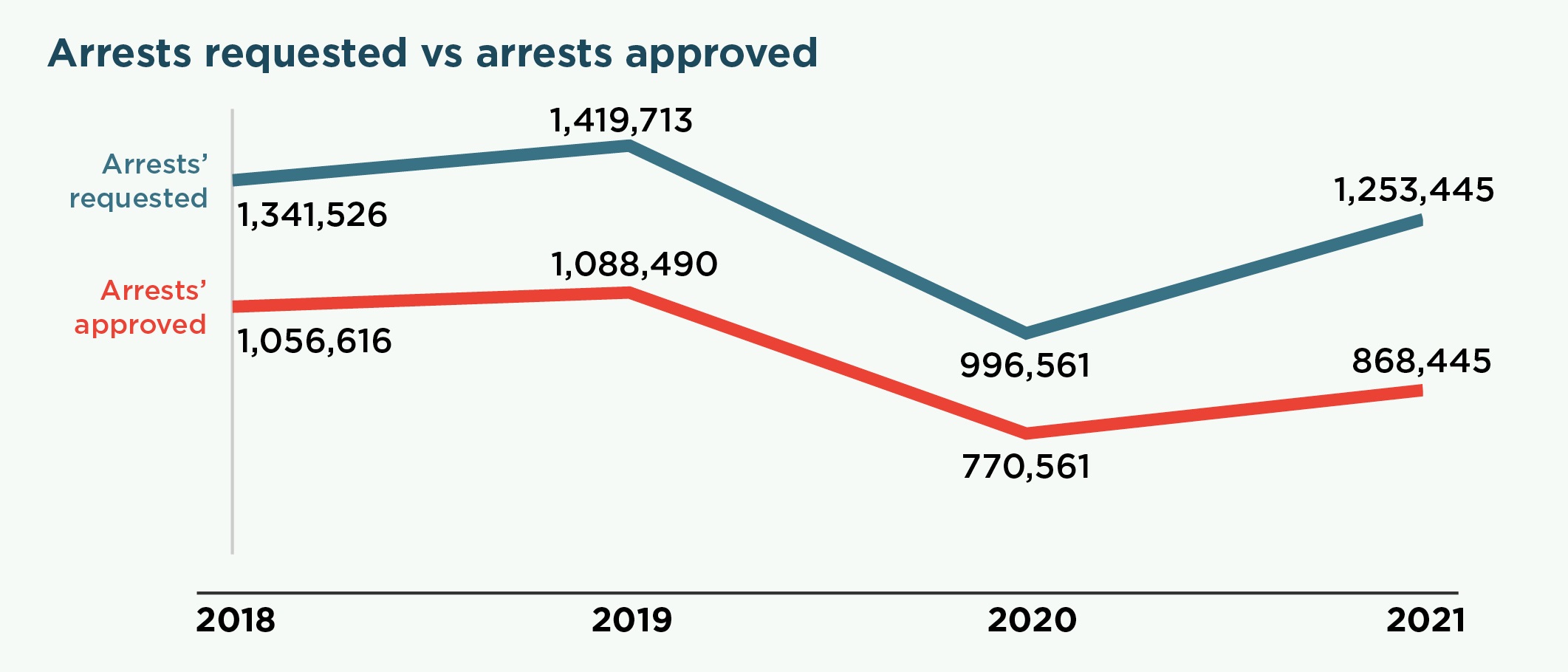

The number of approved arrests, not surprisingly, saw a significant drop in 2020 as the pandemic’s restrictions on movement took its toll. Despite bouncing back somewhat in 2021, it remains lower than in previous years. Both 2018 and 2019 saw continued growth in the number of arrest requests (and arrests approved).

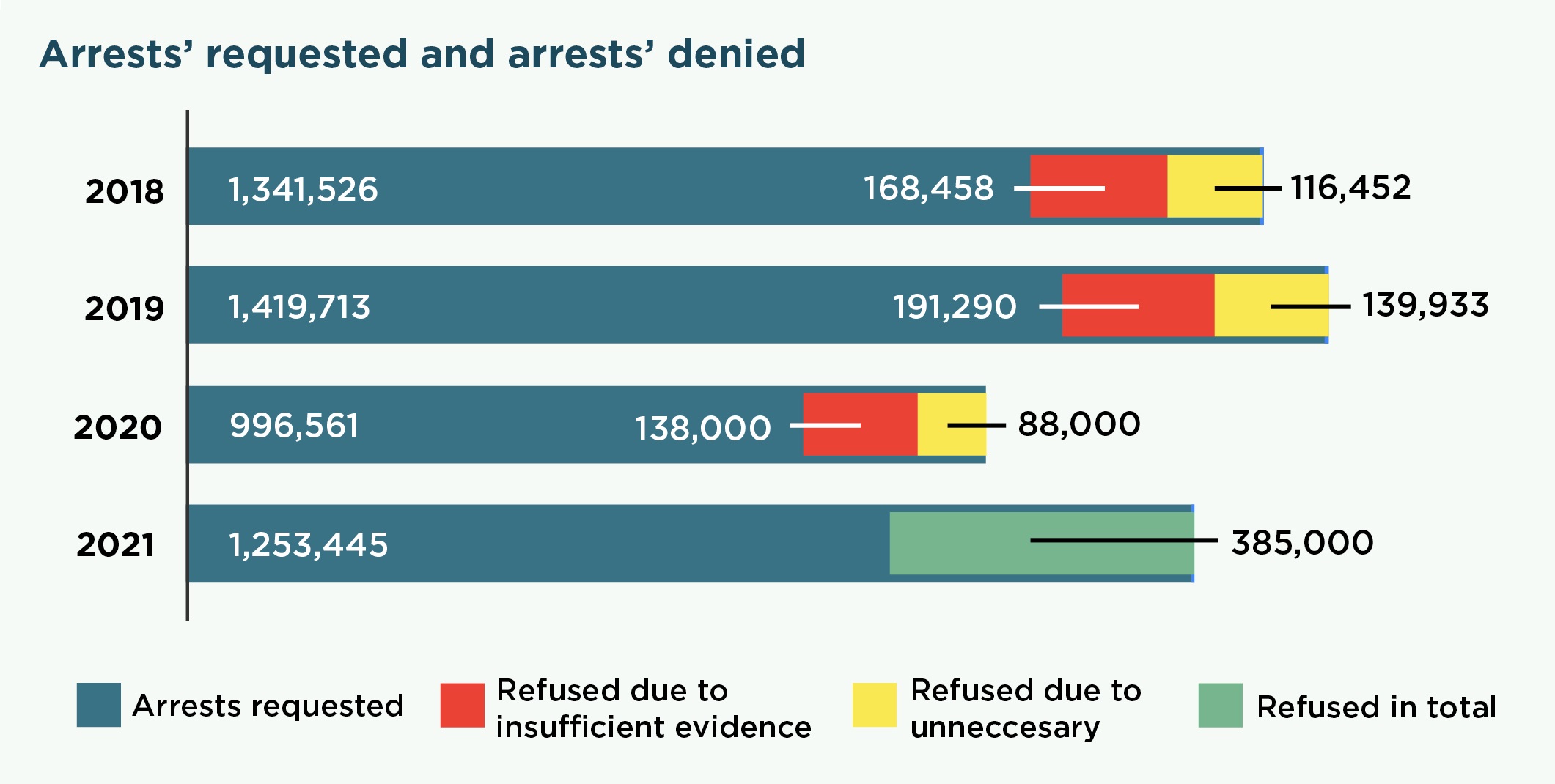

The number of denied arrest requests (prosecutors may deny the police’s request for formal arrest) in 2020 remained stable compared with previous years, hovering between 22% and 24%. It shot up to almost 31% in 2021. Prosecutors can deny arrest requests for the same reasons they decide to drop a prosecution – for insufficient evidence or deemed unnecessary.

The graph below shows approved arrests vs those denied for 2018 to 2021. Unfortunately, as with prosecutions dropped, the new work reports for 2021 no longer distinguish between the two reasons for denying arrest.

Secret and extra-judicial detentions

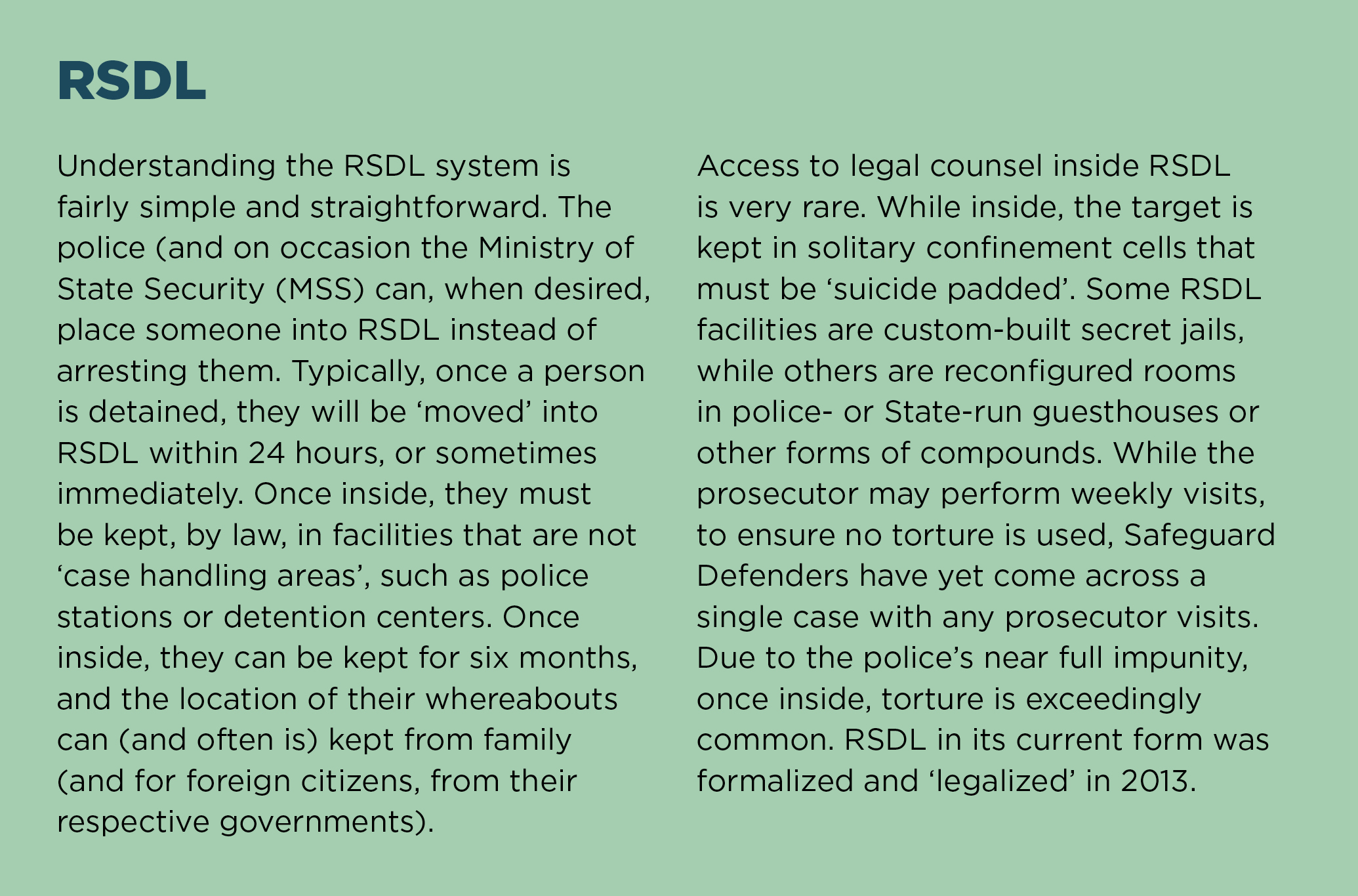

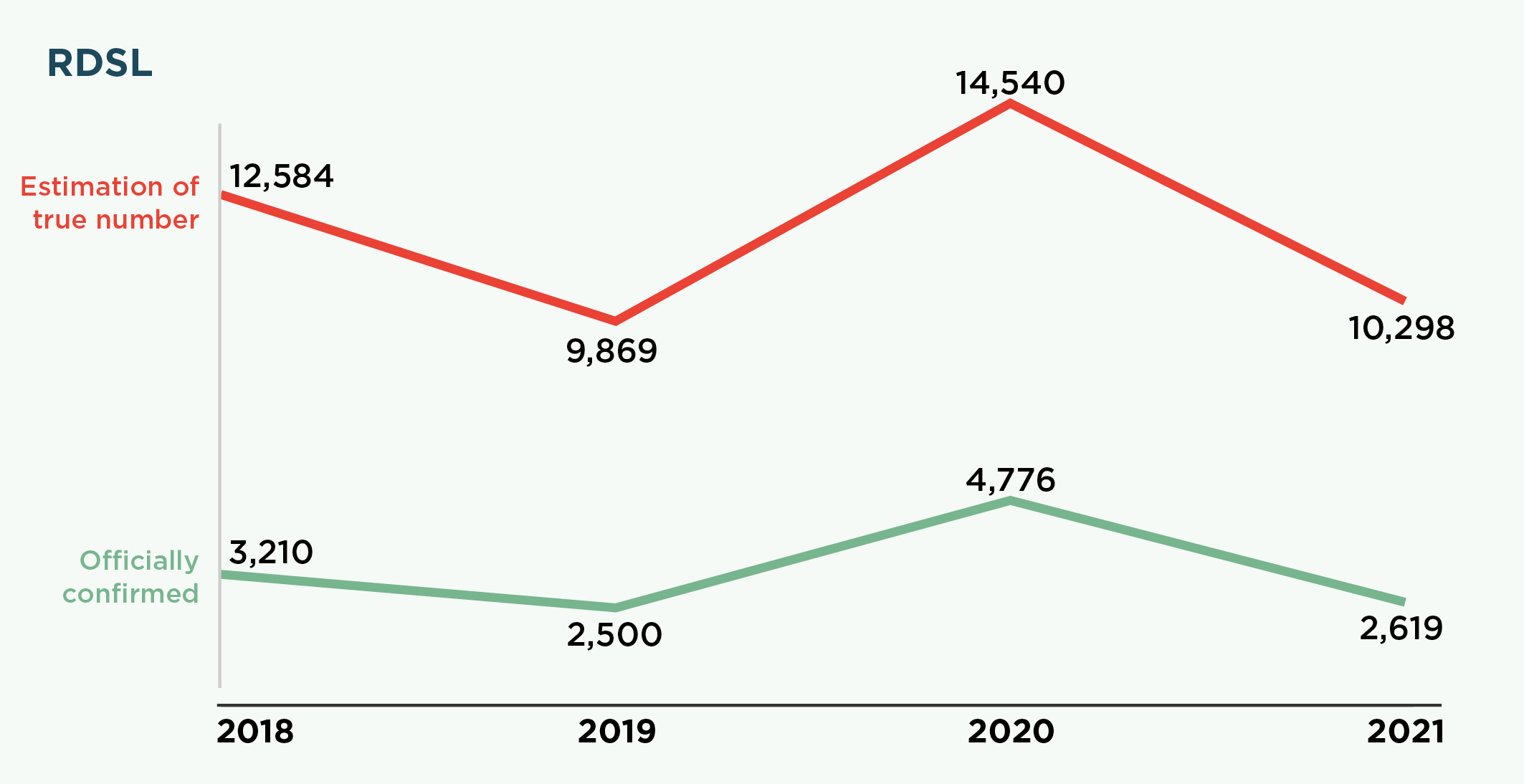

Despite arrests, prosecutions, trials, and sentencing taking a big hit in 2020, data from Safeguard Defenders, drawing from the SPC’s China Judgment Online database for RSDL, and from CCDI data releases for Liuzhi (see explanation of the two systems below), the two systems for secret detention and extra-judicial arbitrary detention saw no such decline. In fact, in 2020 the use of the RSDL system shot up significantly and continued to be used extensively in 2021.

It is unlikely that the growth in RSDL and Liuzhi has been because these secret and isolated detention systems were preferred due to COVID restrictions. Both systems are personnel-heavy, the number of arrests, although falling, was still high, and crucially, both systems have seen sustained growth over the past five to 10 years, well before the advent of the pandemic. While one could expect to see an increase in house arrests due to COVID restriction measures, there is no logic that COVID would lead to higher use of neither RSDL nor Liuzhi.

For RSDL, two sets of data show developments in 2020/2021 compared with 2018/2019, one draws only from those cases logged in the official SPC database, the other uses estimates based on the known limitations of the database.

For RSDL, two sets of data show developments in 2020/2021 compared with 2018/2019, one draws only from those cases logged in the official SPC database, the other uses estimates based on the known limitations of the database.

The data show that both secret detentions (RSDL) and secret, extra-judicial, and arbitrary detentions (Liuzhi) are here to stay, and will likely continue to see continued expansion in the future.

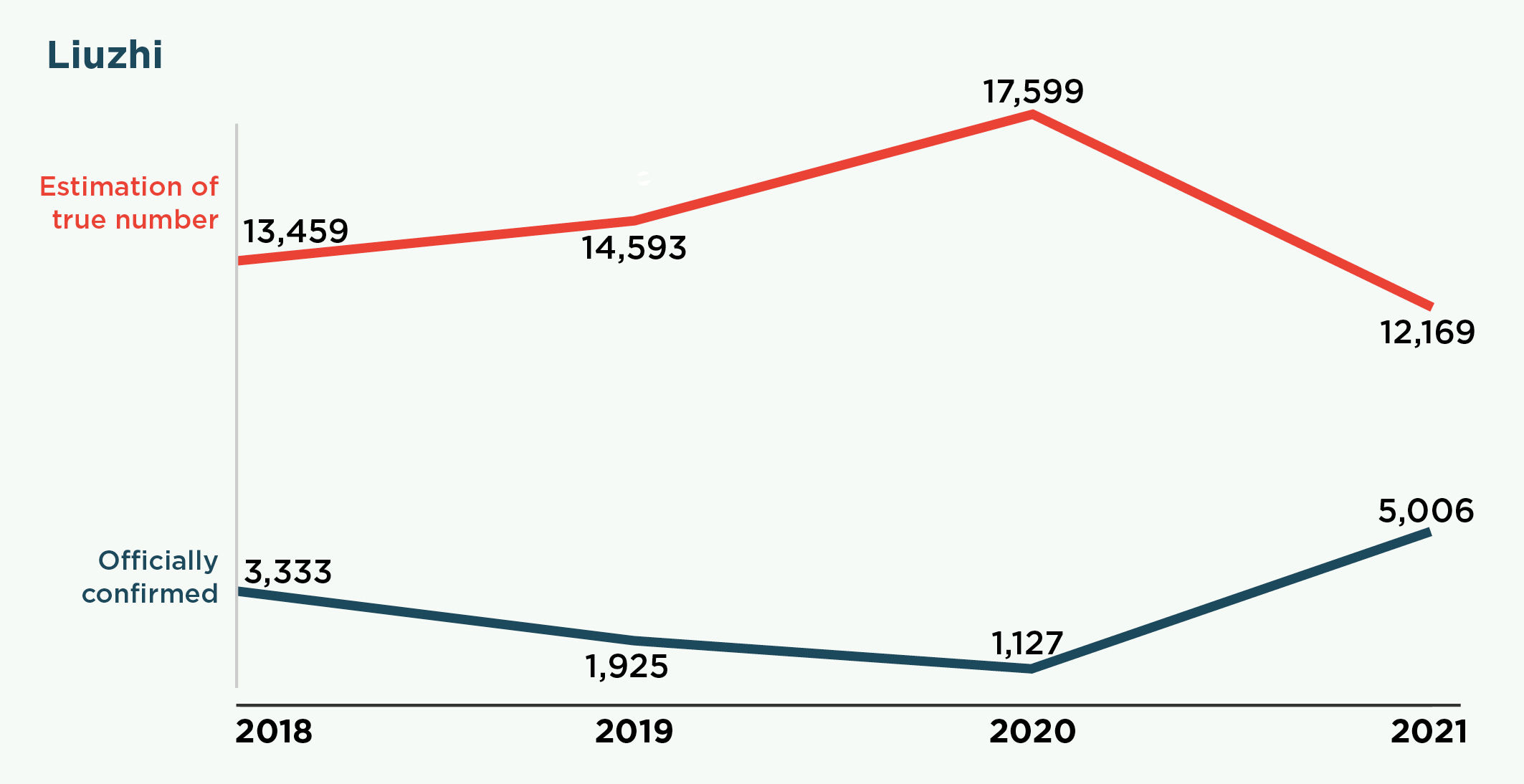

For Liuzhi, two sets of data, for the same period exist: one showing the number of cases acknowledged officially by CCDI, often spanning just a few provinces for each year, and an estimate for nationwide use based on those selected provinces.

For Liuzhi, two sets of data, for the same period exist: one showing the number of cases acknowledged officially by CCDI, often spanning just a few provinces for each year, and an estimate for nationwide use based on those selected provinces.

For more information, see Safeguard Defenders’ recent investigation China’s Pincer move against regulated detentions. For more information on the methodology used to complement the official data on RSDL, see Rampant Repression, while for Liuzhi see our evidence submission to the UN.

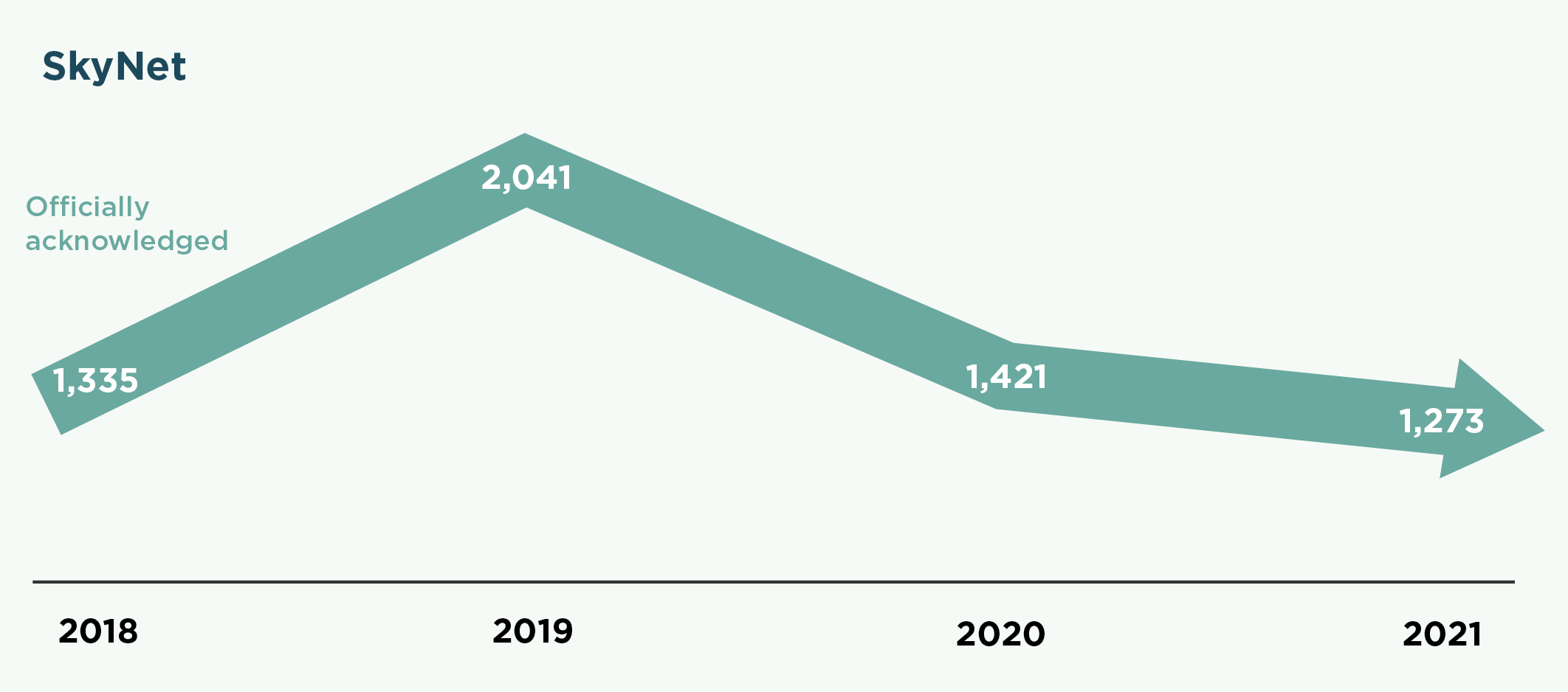

Hunting fugitives overseas

China’s pursuit of so-called “fugitives” overseas has continued at surprising levels during the pandemic, despite major disruptions to access to travel internationally. As exposed in our report Involuntary Returns, Beijing routinely uses methods that violate international law and target countries’ national sovereignty, including kidnapping and harassment.

In 2018 and 2019, record-high annual numbers of claimed successful ‘returns’ were recorded. 2020 and 2021 continued to see significant returns, although they fell about 20.2% to 2,694 (2020 and 2021) from 3,376 (2018 and 2019).

In 2018, the then newly established National Supervision Commission (NSC) took over Operation Sky Net, the global programme hunting ‘fugitives’, an operation intricately linked to Xi Jinping’s domestic “anti-corruption” campaign. The NSC also runs the secret and extra-judicial Liuzhi detention system mentioned above.

Despite continued lockdowns and travel restrictions, China announced during the 2022 National People’s Congress that Sky Net would be expanded this year through the pursuit of other forms of international cooperation, including ‘piggybacking’ on China’s Belt and Road Initiative. So far, neither the Party nor State have provided any further details.

For more information on China’s announced intention to expand Sky Net, see Safeguard Defenders’ article China announces expansion of Sky Net and long-arm policing. For detailed information on Sky Net’s worldwide operation, which has netted over 10,000 returns and many more failed attempts, see Safeguard Defenders’ ground-breaking report Involuntary Returns.

Related issues

House arrests

A brand new investigation from Safeguard Defenders, out early summer, will present detailed data on the use of house arrest (RS, or ‘residential surveillance’) and is not included in this presentation. It will be the first-ever exposé of the scale of house arrests since Xi Jinping came to power.

Exit Bans

A new report from Safeguard Defenders, tentatively entitled Trapping prey in the cage - China's expanding use of exit bans, will be released this summer, and will present detailed data on the use of Exit Bans and is not included in this presentation. It will be the first-ever report to present data on the scale and scope on the use of Exit Bans, as well as the evolving legal landscape for how government authorities, including non-law enforcement bodies, issue Exit Bans.

Other data

There is no new data on the number of criminal trials that took places with the accused having legal counsel. The most recent data from the Chinese government is in 2017, when less than 30% had legal counsel.

Likewise, there is little data on how many investigations or how many detentions are carried out by police (before arrest), as the MPS does not issue an annual work report to the NPC.

There is also no data on the use of administrative detentions by the MPS or the policing activities of the MSS.