The disappearance of Bao Fan, China’s Liuzhi system, and the UN connection

Recent reporting by the Wall Street Journal quotes sources confirming the apprehension of Bao Fan, the business mogul, and his placement into the opaque and rarely mentioned nor covered Liuzhi system.

Bao Fan, a financier and chairman of China Renaissance Holdings Ltd, has been missing since February. While suspicion was immediately cast at his detention into either RSDL (“Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location”) or Liuzhi, the only statements made up until now were the he had “become unavailable” and later that he was “assisting in an investigation”. New information now indicates that he is indeed in Liuzhi.

Key points in this web post:

- The disappearance of Bao Fan

- The structure and functioning of Liuzhi

- The reality inside Liuzhi

- The scale and scope of the use of Liuzhi

- How it may constitute a crime against humanity

- The role of the UN in enabling the system

Bao Fan follows in the footsteps of actress Fan Bingbing, tycoon Xiao Jianhua, Alibaba founder Jack Ma, but also a string of other business elites, such as Yim Fung and Mao Xiaofeng, who have gone missing while under some form of investigation, something which has also happened to the likes of former INTERPOL chairman Meng Hongwei and Supreme Court judge Wang Linqing.

Unlike the RSDL system, run by the police, and often used to target human rights defenders, the Liuzhi system, which is near identical in nature, rarely gets mentioned. One reason is that the system is new, and came into effect only in March 2018, with the launch of the new super-body the National Supervision Commission (NSC), but also because its victims, most often Party members, State functionaries, or those accused of economic crimes related to the State, are not particularly sympathetic victims. However, the sheer scope of its use, which by our estimate now surpasses RSDL use, and the near unlimited power of the NSC using Liuzhi, and the fact that it does not, in any way, constitute a judicial proceeding at all, should lead to proper scrutiny.

This post will provide up-to-date data on the use of the Liuzhi system, its background, the powers conferred on those running it, and why it constitutes a crime against humanity on three different counts. It will also show the role that a UN agency is playing in enabling it.

The establishment of Liuzhi and its background

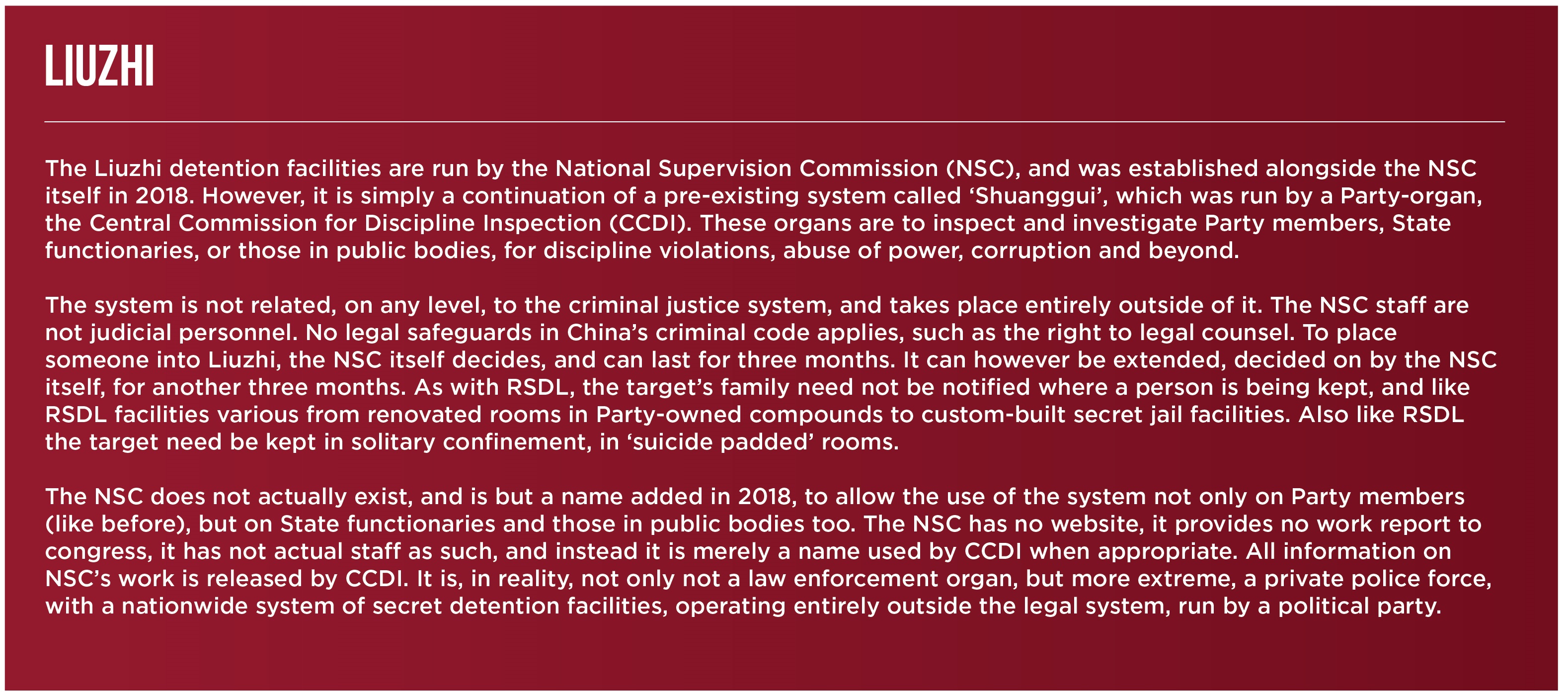

The system itself is not new. A system for detaining Party members being investigated for duty crimes, political offenses, and similar, called Shuanggui has existed since 1990, in regulated form, but goes back further than that. The system is run by a Party entity, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), possibly the most feared organ in China. At the National People's Congress in March 2018, the system underwent a revamp with the establishment of the National Supervision Commission (NSC), and the form for this type of detention morphed into Liuzhi (or "retention in custody").

With this change, placement into this type of secret detention was given additional codification in law, and the scope of those that the NSC can investigate, and take into Liuzhi, swelled, from previously being limited to Party members, to now include State functionaries, including management of State-Owned Enterprises, universities and schools, hospitals, and all other public bodies, including State-owned media. In addition, Liuzhi has also been used on those providing a service, for example, a contractor, to a Party- or State entity. In addition, though not codified in law, it can and has been used to detain those related to a case who are not themselves being targeted by an investigation.

During 2017, two provinces (Zhejiang and Shanxi) and one municipality, Beijing, ran pilot versions of the reform for an expanded NSC, which saw, according to State media reports, the number of people under supervision swell by roughly 300%, 200% and 500% respectively. The baseline for that increase is the number of party members, which stands at roughly 95 million people.

It took less than two months after the system was launched until Chinese news outlet Caixin exposed the first death by torture inside Liuzhi. Chen Yong, in Fujian province, was detained for 26 days in Liuzhi. He was not targeted as such, but was merely the driver for the person investigated (Lin Qiang). The family, having seen his body, reported extensive signs of torture. His wife's requests for recordings of the interrogation sessions were denied. After an initial story from Caixin on the subject, the story went dark, with no further information.

A report by Human Rights Watch, from 2016, focusing on the prior system, Shuanggui, includes information from victims, victims' relatives, lawyers, doctors working inside the system, and investigators, and it paints a picture of not just systematic, but very severe forms, of torture.

Technically, when a case relates to a Party member, it is CCDI that handles the case. For others, it's the NSC. However, the NSC does not actually exist. It is simply a "hat" given to CCDI to use when relating to non-Party members. The office address of the NSC is the same as the CCDI. The NSC has no website. It makes no annual work report to Congress, nor does it issue statements or have a website. All those tasks are handled by the CCDI. There is no such thing as the NSC in any regular sense. For ease, we will refer to the entity using Liuzhi as the NSC.

What Liuzhi entails

Liuzhi takes place in a mix of ad-hoc facilities, such as renovated rooms in hotels, Party-training facilities, and the like, and in custom-built facilities. Once "retained" in such a manner, the person, like with RSDL, shall be kept alone in what are often suicide-padded and proofed cells.

"[The room]…was padded with foam covering; there was an air-conditioner and an exhaust fan. There was no day or night as the lights were lit all the time, there were no windows." – A victim, Human Rights Watch, Special Measures

"The only sign of the room's true purpose was the soft rubber walls. They were installed because too many officials had previously tried to commit suicide by banging their heads against the wall" – Description of a facility in Shanghai by Lin Zhe, professor at the Central Party School.

Upon apprehension, the family, as with RSDL, shall be notified, however, there are exceptions to this rule. If the entity responsible for the detention feels notification of family could somehow undermine their investigation, it may choose to not notify. Regardless, the whereabouts of the target need not be disclosed. With RSDL, for which there is more data, it is known that these exceptions are applied systematically.

"I was detained in many different places…during shuanggui. I was detained in a hotel, in a Party school, in the "clean government education center," and other buildings. "– Former victim, Human Rights Watch, Special Measures

Hence, the outside world and families need not know that a person has been taken, and they certainly will not know where the person is held. With this, use of Liuzhi moves from being an arbitrary detention to becoming an enforced disappearance.

As the NSC is not a judicial organ, and their investigations and use of Liuzhi are not criminal procedures, there is no right, in theory or practice, to access legal counsel. In fact, the lack of such is a key component of the system.

You simply disappear. For up to half a year.

In the words of Zhejiang province's anti-graft chief Liu Jianchao: "These are not criminal or judicial arrests and they are more effective." Jiang Mingan, a Peking University law professor, elaborated further: corruption cases are "heavily dependent on the suspect's confession. (...) If he (the suspect) remains silent under the advice of a lawyer, it would be very hard to crack the case".

The decision to place someone in Liuzhi is reviewed and approved by the NSC itself. The "retention" can last for three months, and upon approval from the NSC (itself), extended for an additional three months, bringing the total to six months, the same as RSDL. There is no external review, nor any procedures for appealing the decision, except to the NSC itself.

"The ways they were treated were all different. Some [interrogators] were more civilized; some more barbaric. In one case, the man was beaten to death… [I]n another involving an eviction officer and a farmer, they were beaten up…" – A lawyer, Human Rights Watch, Special Measures

The NSC likewise carries the power to conduct technical surveillance, carry out searches, question witnesses, place exit bans on people, freeze and confiscate assets, and may issue warrants for people's "retention", which Police are obliged to assist with carrying out.

"In the cases I've handled, generally they collapse after persevering for three to five days, and they'd answer everything you ask, they'd be very cooperative. Those who manage more than a week are [already] tough guys" – A CCDI interrogator, Human Rights Watch, Special Measures

"Their requirement for us doctors was to keep them safe. That meant, don't let them die. A dead person would create big problems. Someone who is only injured doesn't matter." – A doctor describes their role in the system.

Upon conclusion of the investigation, a case may be transferred to the Prosecutor's office and the person handed over to the Police for detention and arrest, but it is rare. If so, the Prosecutor will bring prosecution of the person using evidence provided by the NSC and secured during the person's time in Liuzhi. The Police, the Prosecutor's office and courts are all key targets of the NSC's supervision work too.

Placement into Liuzhi is, in effect, a punishment itself.

"Being subjected to cold and hunger is quite normal… there are also [other forms of] torture, like being strapped to chairs, beaten, insulted, deprived of sleep… there are varying degrees of torture in the cases I have handled" – A lawyer, Human Rights Watch, Special Measures

Dui Hua has published an overview of how such facilities look, drawing from occasional information released in State media, which provides ample insight. For more information on torture techniques used in China in general, see Safeguard Defenders Battered and Bruised, or Safeguard Defenders RSDL-specific report Locked Up.

The NSC has also since its establishment been given overall command of China’s SkyNet operation, which includes FoxHunt, its global fugitive hunt program, as outlined in great detail in SD’s report Involuntary Returns.

The scale of its use

The scope and scale of Liuzhi, like with RSDL, is treated like a State secret, and little information is released to the public, nor included in the CCDI’s annual work report to the Party Congress each autumn. A variety of estimates have been given in the past, back when it was called Shuanggui and only used on Party members, but most of them are estimates with little to known data to back it up.

However, scouring the internet for partial information releases, and piecing together that data, can actually provide some guidance, and even precise figures. For example, CCDI has on occasion, but never with regularity, released figures on Liuzhi use related to specific campaigns launched.

For part of 2021 (for March to June only) CCDI says 1,760 people were placed into Liuzhi related to its specific campaign targeting law enforcement officials. Another data release, covering February 27 to the end of July of the same year, placed the number, for the same campaign, at 2,875. This campaign continued throughout the year, and using that data, we can estimate that during 2021 this campaign alone disappeared some 5,280 to 6,900 law enforcement officers. And this was at the height of Zero-Covid.

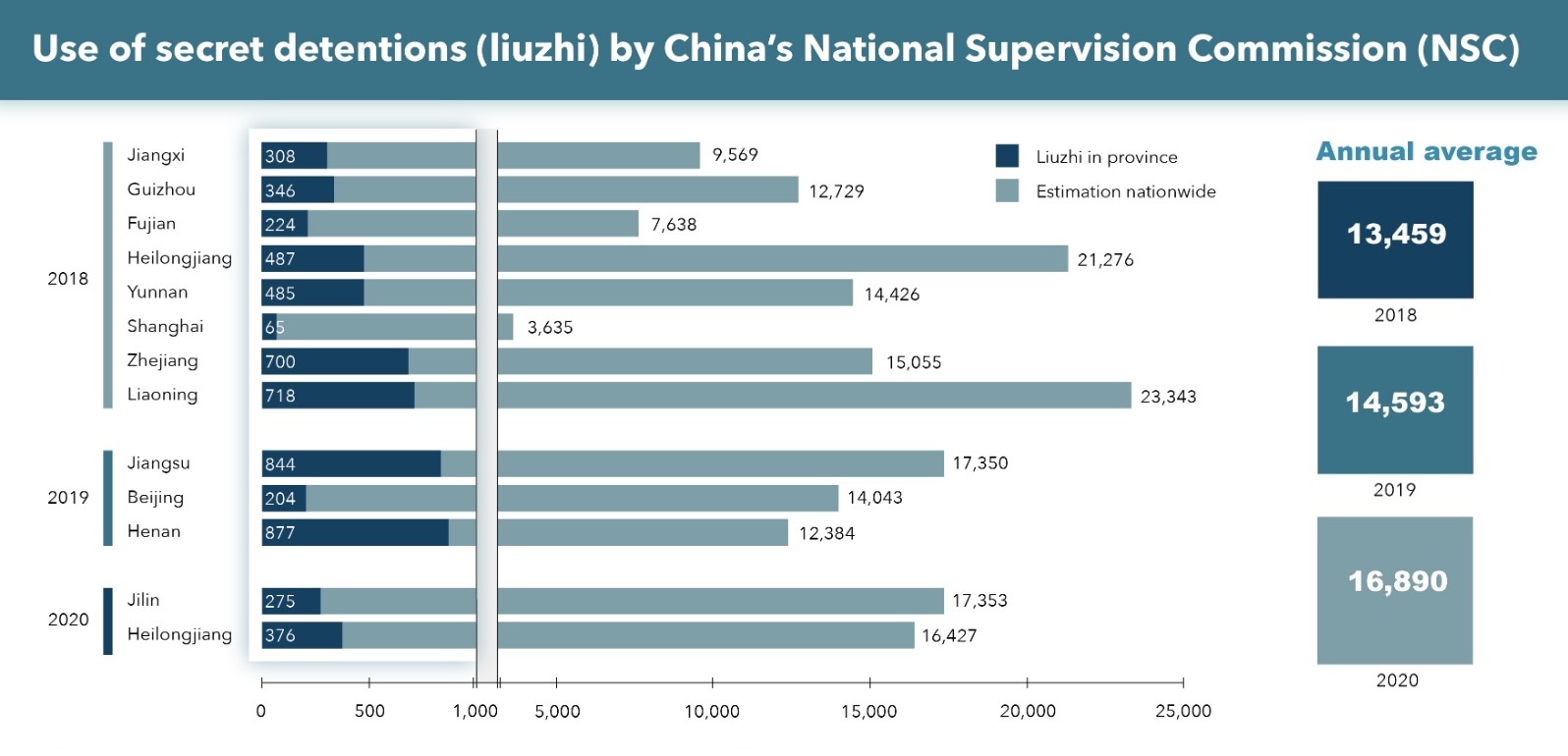

However, better still is relying on sporadic data from some provinces. Which provinces releasing such data vary from year to year, and many times the data is not for the full calendar year, but spans only a portion of it. For a rough estimate, we take the data from each province, and extrapolate it to a full calendar year. We can then extrapolate it to make the figures nationwide and can see a rough estimate.

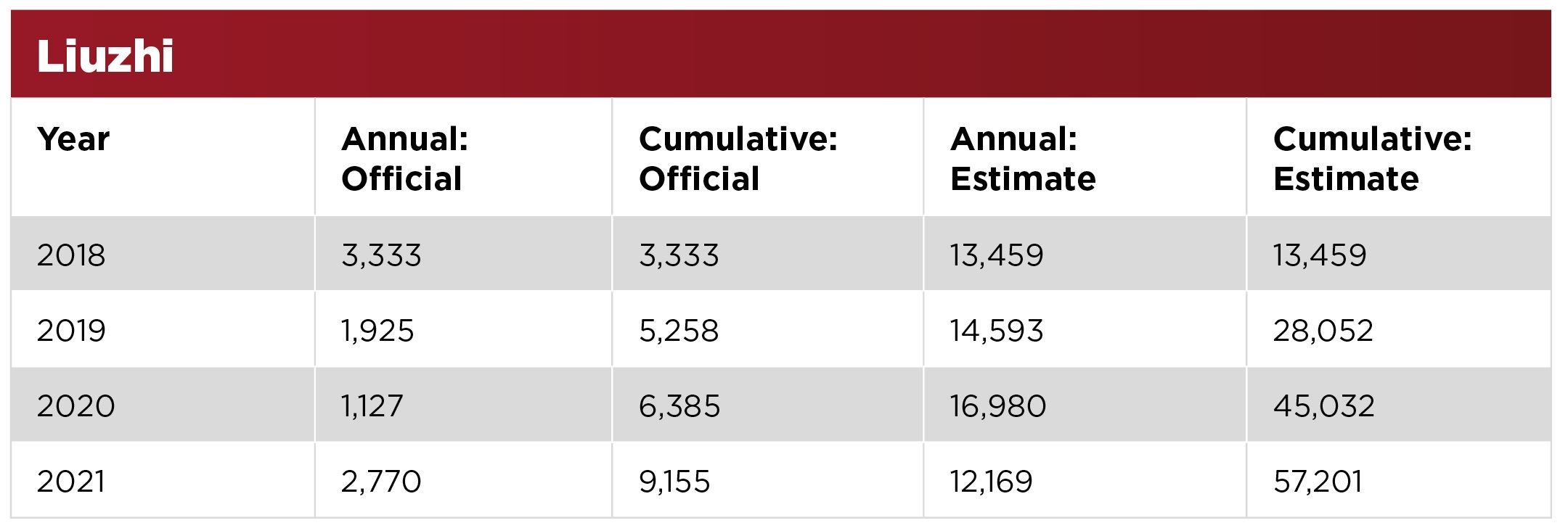

As no province is likely to reflect the average, we do this for all provinces that have released such data for the given year, and can move towards a better picture. With this collection, we can secure two numbers, a) the bare minimum number of cases as acknowledged by the CCDI/NSC, and b) a rough estimate on a province-by-province basis for the country as a whole. Based on the data so far collected, it would appear as in the table below.

Note that the total for 2021, drawing only on data released by a few select provinces, is actually lower than the number for the campaign against law enforcement officers alone, and for which data spans only some five months. Hence, the real number is certainly much higher, and the estimates offered here are likely significantly lower than reality. However, without more data no further estimations are possible.

The cumulative estimate, as it is, from March 2018 up until end of 2021 thus stands at ~60,000 victims, but it is, as said, likely a significant underestimation.

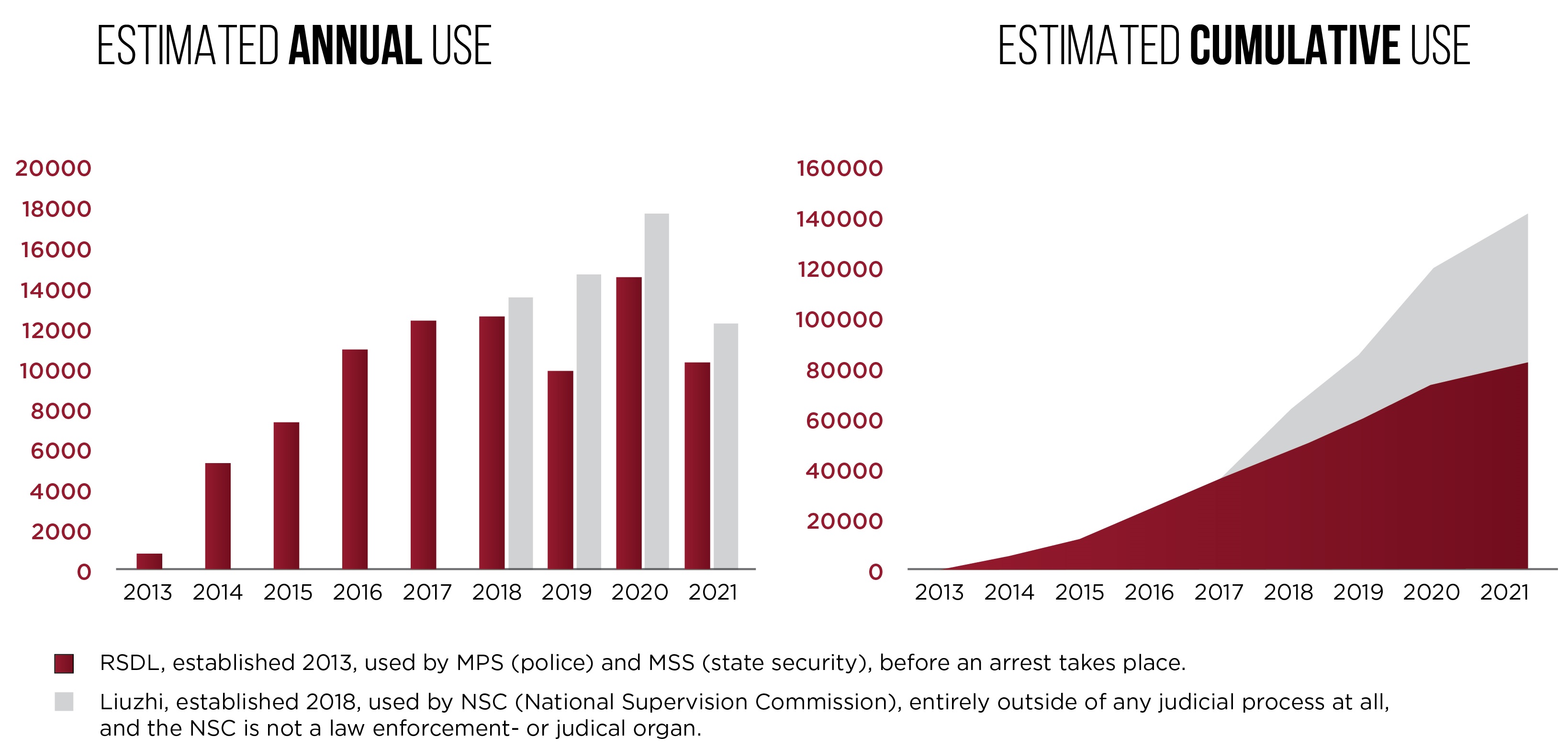

Due to extensive data collection carried out by SD on RSDL, it is also possible to compare the two, as both constitute systems for enforced disappearance, are very similar in design, yet focus on different target groups. Current data on both systems, up to 2021, is presented in the chart below.

Whether one relies only on the number of cases as acknowledged by the CCDI/NSC, or estimates of what these figures mean on a nationwide scale, the use of Liuzhi cannot be classified as anything other than widespread and systematic.

For more information on data on RSDL use, see this data collection 2021, or this brief investigation on RSDL and Liuzhi 2022.

For data collection by province for 2018 to 2020, which has been provided by SD to the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) and Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (WGEID), see the table below. The submission itself can be found here. Note: The below data table does not include 2021, for which three provinces have provided data for (Jilin, Inner Mongolia, and Shanxi).

Issues making it a crime against humanity

There have been numerous accounts of treatment in Shuanggui and now Liuzhi over the years, painting a grim picture. However, due to the nature of the victims, it is exceedingly hard to collect enough victim testimonies to show its systematic nature (nor, for that matter, to verify any such information). However, using Party/State provided data (above), the system itself can be established as amounting to what may be a crime against humanity on three grounds:

-

To start with, according to one statement by Liu Jianchao, head of the Zhejiang Supervision Commission, the average stay inside Liuzhi was 42.5 days. Other statements point to similar numbers. The use of solitary confinement, for investigation purposes, for a prolonged period (above two weeks) counts as an act of torture. The damage caused at this point becomes irreversible and permanent. For more details on this issue, see Safeguard Defenders' investigation into the status of the use of solitary confinement within the RSDL system.

- Likewise, as Liuzhi exists outside the judicial system, essentially run by what can be called the Party’s own internal police force, all “retentions” qualifies as arbitrary detention.

- The systematic use of the system to keep people at unknown locations qualifies its use as amounting to enforced disappearances.

On all three counts, if done systematically or in a widespread fashion, it may amount to a crime against humanity according to the Rome Statute/International Criminal Court (to which China is not a party).

The UN and the NSC

Despite the WGAD/WGEID having reached out to China regarding the issue of Liuzhi, and how it contains numerous violations, and UN organs having already established that RSDL, less extreme in form than Liuzhi, constitutes enforced disappearances and being rife with torture, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has no qualms about cooperating with the NSC.

In fact, UNODC has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the NSC, but they are refusing to release its content, making it, in effect, secret. This lack of transparency should surprise no one familiar with the operations of UN agencies, nor should its refusal to engage in conversation on the topic.

In their only response to inquiries made by SD, outlined here, the UNODC's John Brandolino wrote that" The United Nations has attached great importance to human rights", yet on 17 October 2019 signed such the agreement, despite it already being well known that a) the NSC is not a law enforcement nor any other kind of judicial organ, and therefore not a counterpart to engage with for judicial cooperation, and b) that the organ, and its predecessor, stands credibly accused of massive human rights violations. Enabling such a body entirely and completely negates the claimed commitment of UNODC to human rights.

In their response, they further state:

"As you are aware, the National Commission of Supervision (NCS) is the supreme supervisory body of the People's Republic of China and is recognized as a legitimate representative of the Government. It is also the main focal point for China's work related to the Convention."

The announcement on signing the MOU stated:

"The new agreement will allow the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and China to strengthen cooperation on the implementation of the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in key areas such as prevention, criminal justice responses to corruption offences, law enforcement cooperation and stolen asset recovery."

And further:

"Under the agreement, UNODC and China will enhance information sharing with respect to research and best practices on the prevention of corruption, trends in international judiciary and law enforcement cooperation related to corruption offences, and stolen asset recovery. Joint training, capacity building programmes and support through projects such as the UNODC and World Bank Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) are envisioned. UNODC and China will also reinforce dialogue and communication on the implementation of UNCAC and work on establishing a communication platform to facilitate exchanges among anti-corruption authorities of UNCAC States parties."

The irony of the self-proclaimed guardian of the UN Convention against Corruption cooperating with a body operating outside any of the minimum legal bounds provided for in countless UN Treaties and Conventions cannot be lost on anyone. Unfortunately, the joke is on the terrorized victims, both inside and outside China, given the expressed reference to "step[ping] up practical cooperation in the area of fugitive repatriation," as stated by Yang Xiaodu, Chairman of the NSC.

The UNODC said to SD that it does not foresee operative cooperation as part of this agreement, but their choice of words is not reassuring. China certainly seems rather pleased with having entered into such an agreement, stating:

"The signing of a MOU on cooperation...has effectively demonstrated China's good image of comprehensively governing the country according to law, and has enhanced the international community's recognition and trust in China's rule of law."

The top funders of the UNODC are countries such are the US, Japan, Norway, and the UK, along with various European Union member states and the EU itself, yet few have shown any interest in the fact that the UNODC is spending their own tax-payer money on assisting a body credibly accused of crimes against humanity, and for severe violations of sovereignty as part of its transnational repression operations tied to the global SkyNet program.

Perhaps with Bao Fan now reported as having been placed into Liuzhi, the system will receive the scrutiny so badly needed, and UNODC forced to answer why it is enabling the body responsible for it.