Xi Jinping III - What to expect

In view of the 20th Communist Party of China Congress and Xi Jinping’s most likely confirmation as its Secretary General, a brief overview of our recent reports and insights into three main correlated trends in growing gross human rights abuses during his past two mandates at the helm of the People’s Republic of China should provide useful insight into what more to expect under his third term: the widespread and systematic use of enforced disappearances and torture, a flawed criminal justice system being hollowed out, and the rapidly expanding illegal transnational policing operations around the globe.

1. Expanded use of Enforced Disappearances and Torture

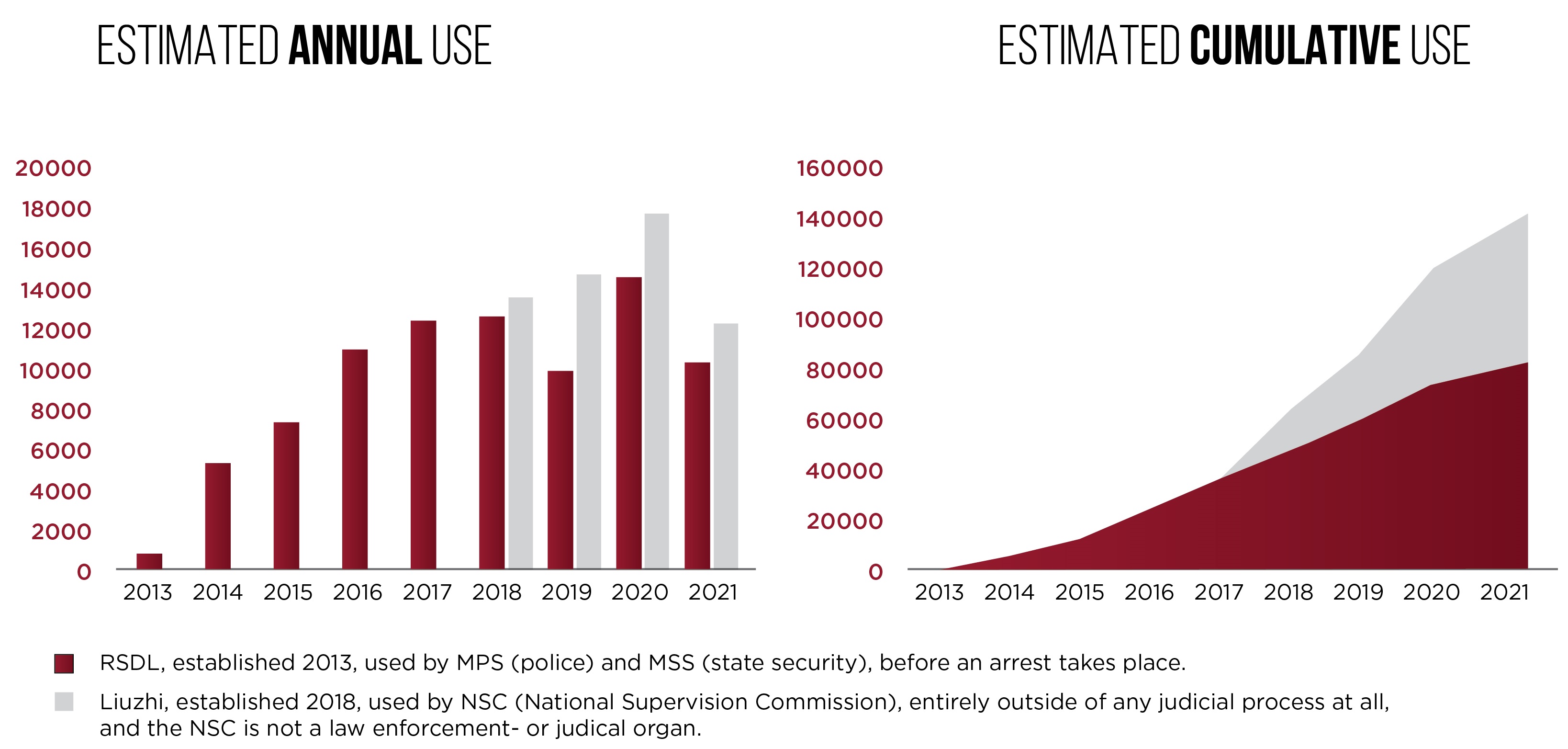

Under Xi’s reign, the use of enforced disappearances through one of the PRC’s many dedicated systems has grown at a stellar pace. “Legalized” under Chinese law in 2013, Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) - the first system for enforced disappearances - has become a regime favorite to crack down on human rights defenders, those suspected of “national security crimes” and foreigners: the system outlined in our graphic report Locked Up allows the security apparatus to disappear individuals for up to six months without access to a lawyer (or consular assistance in the case of foreigners).

Under Xi’s reign, the use of enforced disappearances through one of the PRC’s many dedicated systems has grown at a stellar pace. “Legalized” under Chinese law in 2013, Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL) - the first system for enforced disappearances - has become a regime favorite to crack down on human rights defenders, those suspected of “national security crimes” and foreigners: the system outlined in our graphic report Locked Up allows the security apparatus to disappear individuals for up to six months without access to a lawyer (or consular assistance in the case of foreigners).

Neither the victim nor their family members are informed of their whereabouts. Taking place before any trial, torture within the system aimed at obtaining forced confessions is rife.

Well-known former inmates include the two Canadian hostages Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, now-exiled artist Ai Weiwei, human rights lawyers Wang Yu and Wang Quanzhang. While the system in its current for was established as Xi came to power, its use has expanded during his second mandate period, with local police started using the system, unlike in earlier instances, and with it being used increasingly on non-national security crimes. The pandemic era as sent he continued high level use of the system, which is likely to expand further.

United Nations Human Rights Procedures have repeatedly condemned the practice of incommunicado detention in RSDL as “tantamount to enforced and involuntary disappearances” and “arbitrary detentions”, calling upon the Chinese authorities to halt the practice “as a matter of urgency”.

Inscribed in the National Supervision Law of 2018, Liuzhi functions in a similar fashion to the RSDL system, and is the second system established for Enforced Disappearances. Incommunicado detention for up to six months with an aim of obtaining forced confessions. It only took a mere month after its institution before the system claimed its first deadly victim.

Inscribed in the National Supervision Law of 2018, Liuzhi functions in a similar fashion to the RSDL system, and is the second system established for Enforced Disappearances. Incommunicado detention for up to six months with an aim of obtaining forced confessions. It only took a mere month after its institution before the system claimed its first deadly victim.

Unlike RSDL, liuzhi is not even formally a part of pre-trial judicial investigations but is operated by the National Commission of Supervision (NCS), a state front for Party body Central Commission of Disciplinary Inspection (CCDI) that answers solely to the CPC’s Politburo and is beyond any checks or controls by the judiciary.

By law, its officials are neither law enforcement nor judicial personnel, so even the few theoretical legal safeguards against the use of torture do not apply to them.

Based on the one-year pilot project before the NCS’s launch, it has a mandate to investigate a group of up to 300,000,000 people. The system was created to expand the scope of supervising and “controlling” not only party members, state functionaries, management at schools, hospitals, universities, mass organizations and state-owned enterprises, but also journalists, business people and local contractors.

Safeguard Defenders’ continued analysis of publicly accessible data leads to a modest estimated accumulated use of the systems on at least 104,492 individuals since 2018 (47,291 into RSDL; 57,201 into Liuzhi). These include a number of high-profile targets such as actress Fan Bingbing, Supreme Court judge Wang Linqing, former Chairman of Interpol Meng Hongwei (and probably mogul Jack Ma), as well as numerous foreign citizens. If we add data on RSDL use between 2013 and 2017, the number rises to 141,167. The widespread and systematic use of enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and torture is a crime against humanity under the Rome Statute.

While RSDL was established as Xi came to power, and expanded during his second mandate period, the Liuzhi system, and the sweeping powers of the NSC. came to be at the start of his second mandate period and is almost certain to play an increasingly important role in China.

The RSDL and Liuzhi systems, as well as the expanded use of house arrests with no judicial review, hollows out the already flawed criminal justice system, offering the Police and Party news means to persecute without having to use normal judicial procedures, and this represents a major threat to even modest "rule by law" functionality within the Chinese judicial system.

The PRC’s Ankang system is another extra-judicial system to cruelly crack down on dissent. The system’s survival despite formal changes to the legal framework under the new Mental Health Law passed a decade ago provides further demonstration of the PRC’s blatant disregard not only for international human rights norms, but even its own legal standards aimed at preventing gross human rights abuse.

The PRC’s Ankang system is another extra-judicial system to cruelly crack down on dissent. The system’s survival despite formal changes to the legal framework under the new Mental Health Law passed a decade ago provides further demonstration of the PRC’s blatant disregard not only for international human rights norms, but even its own legal standards aimed at preventing gross human rights abuse.

Safeguard Defenders’ Drugged and Detained: China’s psychiatric prisons provides a chilling account of one of the ways the CPC uses to disappear critics – forced hospitalization in a psychiatric facility without medical justification. This is the system used on Dong Yaoqiong, better known as "Ink Girl", after smearing ink on a poster of Xi Jinping. She was in the news again recently as her father, who had tried to help her, and who had been detained by police, died in detention recently. It may yet be employed on the man who, just before the start of the 20th congress, launched a protest in Beijing at the Sitong bridge, which received widespread media attention.

Called Ankang after the system of police-run psychiatric prisons launched in the 1980s, nowadays, most victims are locked up in regular psychiatric wards, meaning that doctors and hospitals collude with the CCP to subject victims to medically-unnecessary involuntary hospitalizations and forced medication.

2. A flawed criminal justice system being hollowed out

China’s Criminal Justice System in the Age of Covid is the latest installment in Safeguard Defenders’ ongoing monitoring of the PRC’s track record for a Party-controlled judicial system rigged to produce guilty verdicts.

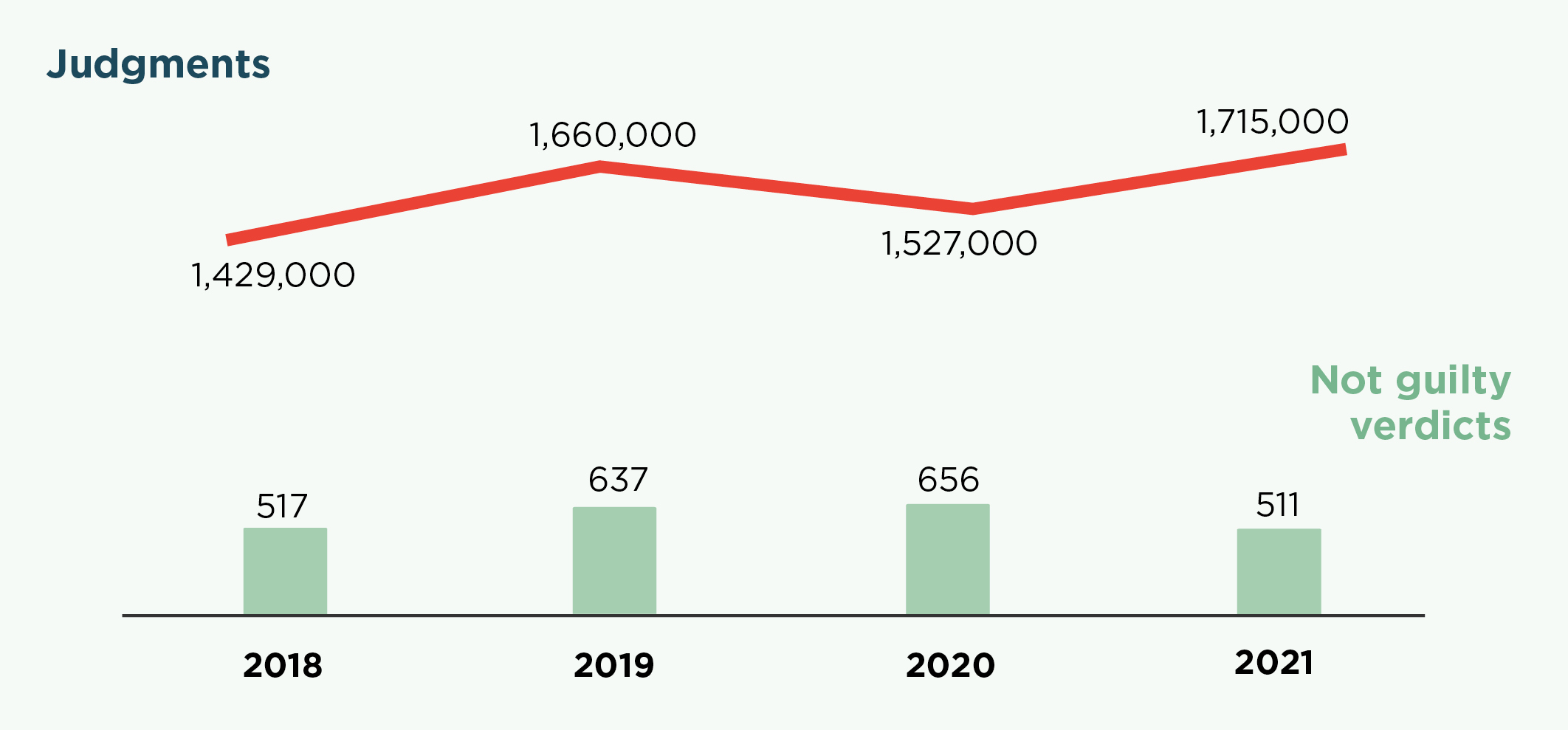

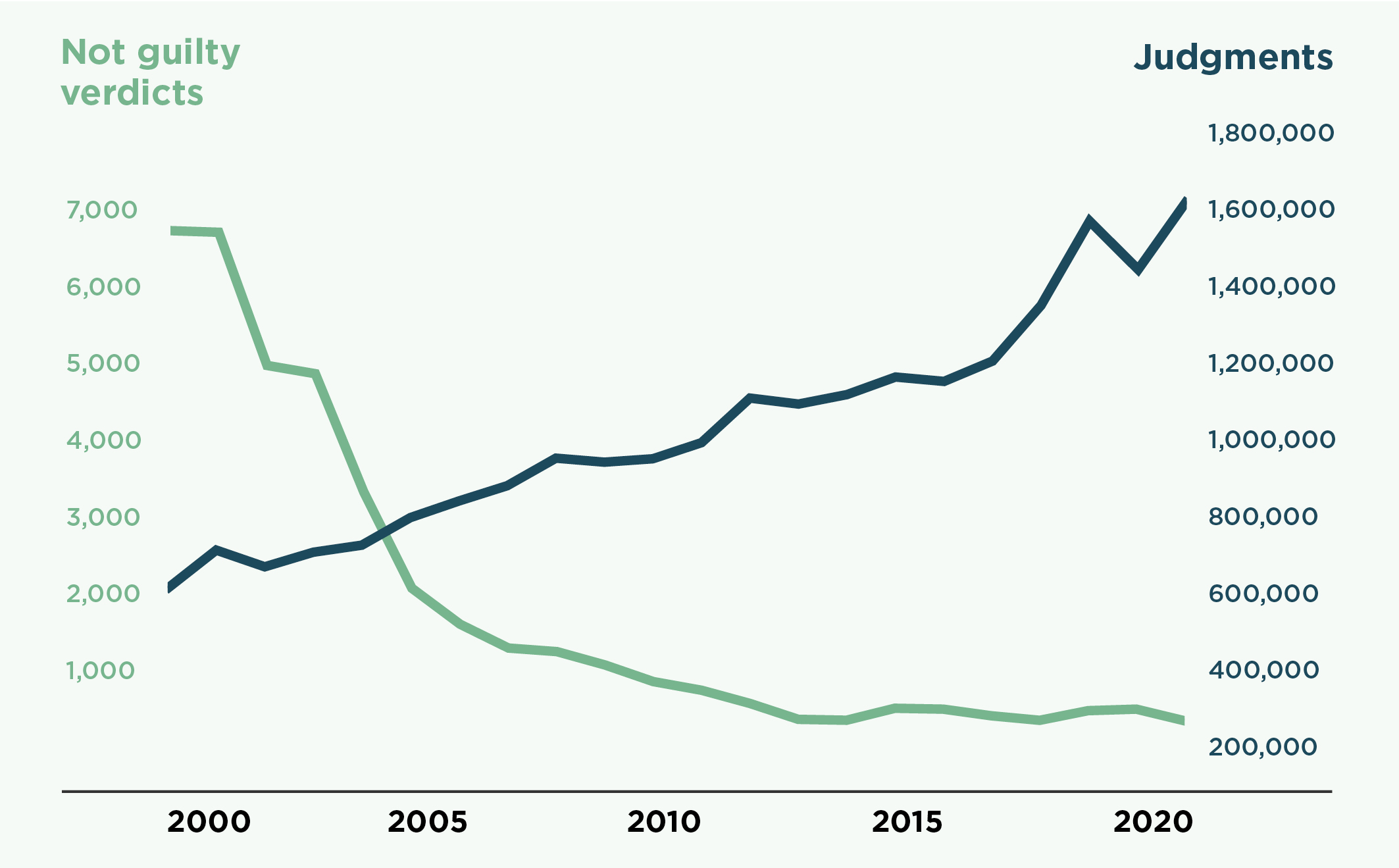

In 2021, over 99.97% of criminal trials at first instance resulted in guilty verdicts, a record high since 1980 when data was first recorded. Likewise, the number of not-guilty verdicts continued to plummet, to a record-breaking low of only 511 last year - this compared with more than 1.715 million judgments made.

The number of trials at first instance saw a small decline in 2020, due to the Covid pandemic, to 1,116,000, but by 2021, it had almost bounced back, reaching 1,256,000, very near the previous record high of 1,297,000 in 2019.

These numbers should come as no surprise. As some of the investigation methods in the above-described systems already outlined: forced confessions are a regime favorite – occasionally also broadcasted through its propaganda channels for maximum impact on the communities most at risk – and the judiciary’s primary role is to uphold the Communist Party of China with Xi Jinping at its core.

To further ensure the certain outcome, in recent years even the most basic judicial safeguards guaranteed by the PRC’s own laws have been further hollowed out. Our Access Denied series documents how the Chinese police forces victims - many of whom are human rights defenders - to take a fake name in pre-trial detention in order to stop them from seeing a lawyer (China’s Vanishing Suspects, 2020); how prisoners, once freed from jail or a detention centers, continue to be arbitrarily detained by the police at their home, at a hotel or in a secret location for weeks, months or even years under the “non-release release” phenomenon (China’s False Freedom, 2021); or the multitude of ways the authorities are increasingly using to deny suspects access to independent legal counsel (China’s Legal Blockade, 2021).

Taken together, it shows how the remaining part of the criminal justice system (the part not already taken over via the use of RSDL and Liuzhi) is being further undermined, weakening already scarce legal safeguards. Many of these trends first appeared, or grew stronger, during Xi's second mandate period, casting a bleak shadow over what to expect during his third mandate period.

Documenting these trends may become increasingly difficult in the future, as any positive steps towards greater transparency are rapidly being undone, as denounced in China’s Missing Verdicts – the Demise of CJO and China’s Judicial Transparency.

This trend may well be linked to the same rationale underpinning the last highlight of trends in this post: China’s growing transnational policing operations through a combination of legal and illegal methods, and the related perceived need to keep outsiders “from looking in”.

3. The global hunt for “fugitives”

Safeguard Defenders’ soon to be available permanent online resource center to counter extraditions and/or deportations to China and Hong Kong which will accompany our ongoing direct actions in support of those most at risk, has been anticipated by a series of releases documenting the PRC’s rapidly growing and increasingly brazen illegal transnational policing operations.

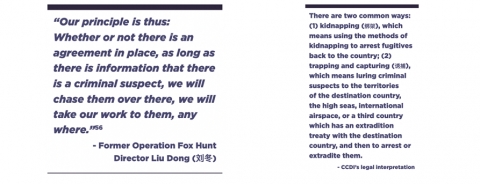

Involuntary Returns: China’s covert operation to force ‘fugitives’ overseas back home (2022) blows the lid off China's far-ranging long-arm policing operations Sky Net and Fox Hunt, the 10,000 targets so far returned, and the legal mandate allowing for kidnapping abroad provided by the same Party body responsible for mass enforced disappearances in the Liuzhi system.

Involuntary Returns: China’s covert operation to force ‘fugitives’ overseas back home (2022) blows the lid off China's far-ranging long-arm policing operations Sky Net and Fox Hunt, the 10,000 targets so far returned, and the legal mandate allowing for kidnapping abroad provided by the same Party body responsible for mass enforced disappearances in the Liuzhi system.

“Any means” go to ensure the return of targets. Legally sanctioned methods under the PRC’s National Supervision Law range from detaining family members back in China, to sending police overseas on secret missions to intimidate targets into returning, to outright kidnappings abroad. Later, at the National People's Congress held in March 2022, the government announced the further expansion of Sky Net, and announced its expansion would be tied to the Belt and Road initiative.

The rapidly expanding global practice poses a severe threat to national sovereignty and individual rights everywhere. National awareness and investigations, as well as targeted actions to counter these operations and protect those most at risk are key to upholding the international rules-based order.

Follow-up investigation 110 Overseas – China’s Transnational Policing Gone Wild uncovered the active adoption of the 2018 national guidelines on involuntary returns methods by county-level Public Security Bureaus and Procuratorates leading to a reported 230,000 individuals “persuaded to return” under a single campaign between April 2021 and July 2022 alone.

The operations include the establishment of “Overseas Police Service Stations” with United Front Work – linked organizations across the five continents in order to “resolutely crack down on crime” and “extend the Procuratorate’s tentacles” worldwide. A central government announcement also established a pilot scheme for 10 provinces to carry out similar work and operations, indicating a further expansion to come.